Unnerved by the undercurrent she detected in his tone, Antonia cried off from their evening's engagements. She did not even risk dinner, requesting a tray in her room on the grounds of an incipient headache.

Ensconced in lonely splendour at the head of the dining-table, Philip sat sunk in thought, his gaze fixed on the empty seat beside him. At the table's end, Henrietta and Geoffrey were deep in machinations.

"I have to say that I'm not a great believer in newfangled notions, yet I cannot see my way clear, in this instance, to agree with Meredith Ticehurst." Henrietta pushed away her soup plate. "There's nothing the least-well, questionable about Mr Fortescue, is there?"

"Questionable?" Geoffrey frowned. "Not that I know of. Capital fellow from all I can make out. Drives a neat curricle with a nicely matched pair."

Henrietta returned his frown. "That's not what I meant." Raising her head, she looked up the table. "Do you know anything against Mr Fortescue, Ruthven?''

The sound of his name shook Philip from his thoughts. "Fortescue?"

Henrietta threw him a disgusted look. "Mr Henry Fortescue-Miss Dalling's would-be suitor. I have to tell you, Philip, that I am not at all happy in my mind about the tack Meredith Ticehurst is taking with her niece. No-and not with the Marquess either, although he is, after all, a man and, one would suppose, capable of taking care of himself."

Recalling the Marchioness of Hammersley, Philip considered that last far from certain. "I know nothing against Mr Fortescue-indeed, what I do know would suggest he is an eminently eligible, even desirable, parti.''''

Having delivered himself of that pronouncement, Philip reached for his wine glass. As he sipped, Henrietta's suppositions and concerns, and Geoffrey's predictably straightforward views, drifted past his ears. Their tacit alliance and their half-formed plans to overturn the Countess's applecart did not even register.

Then the meal was at an end; Philip could not even recall if he had eaten. He did not particularly care; he had lost his appetite, among other things.

But when they gathered in the hall preparatory to quitting the house, destined for Lady Arbuthnot's drum, his gaze sharpened. He glanced at Henrietta, his expression bland. "No doubt you'll wish to check on Antonia before we leave."

"Antonia?" Henrietta looked up in surprise. "Whatever for? She's not seriously ill, y'know."

"I had thought," Philip returned, steel glimmering in his tone, "that you might wish to reassure yourself that her indisposition is indeed merely that, and not something more alarming. She is, after all, in your care."

"Phooh!" Henrietta waved her hand dismissively. "It's doubtless merely an upset brought on by going at it too hard." Slanting him a glance, she added, "Have to remember she's a country girl at heart. She might have adapted well to town life but we've been racketing about in grand style these past weeks. She's entitled to some time to recuperate." Henrietta patted his arm in a motherly way then, beckoning Geoffrey, stumped towards the front door.

His expression stony, Philip hesitated, then reluctantly followed.

They returned from Lady Arbuthnot's drum at midnight; to Philip's relief, Henrietta had shown no interest in attending any other of the parties around town. Heads together, thick as thieves, she and Geoffrey negotiated the stairs; frowning, Philip headed for the library. From the corner of his eye, he caught Carring's expression; he shut the door with a decided click.

He hesitated, then crossed to the sideboard and poured out a large brandy. Cradling the glass, he returned to sink into his chair, the one on the left of the hearth. Slowly, he sipped the fine brandy, his gaze broodingly fixed on the empty chair opposite.

Last night he had paced the hearth rug, glowering, possessed by an impotent and thoroughly uncharacteristic anger. Tonight, the anger was still there but tempered by growing concern.

Antonia was avoiding him; now Carring was regarding him with chilly disapproval.

Philip directed a steely glare at the empty chair. He wasn't at fault. Antonia should have been more trusting- ladies were supposed to trust their husbands-to-be. She loved him-

Philip stopped.

For one instant, his world wavered-then he snorted impatiently.

He knew, beyond all doubt, beyond any possibility of error, that Antonia loved him. He had known it for more than eight years. Her love was there in her eyes, a certain wistfully warm expression glowing in the hazel depths. He had not responded to it years ago but he had recognised it nonetheless. It had been there even then.

Philip let the thought warm him. He took a long sip of his brandy then frowned at the smouldering fire.

If she loved him, she should have trusted him. She should have had more confidence in him. She should have had the courage of her convictions.

Again his thoughts faltered and halted; Antonia possessed abundant courage. The courage needed to fearlessly manage high-couraged horses, the courage to face with equanimity eight long years of seclusion and deprivation she had never been raised to expect. Her reservoir of courage could not be questioned; why, then, would she not face him over this? Why had she so readily accepted the obvious and retreated, rather than confronting him and letting him explain?

Why hadn't she had the confidence in him that he had in her?

Philip slowly blinked, then grimaced and took another sip from his glass.

He had told her he was smitten, that they shared a deep mutual attraction-she knew he desired her. Surely it was reasonable to expect a lady of her intelligence to make the appropriate deduction?

His frown deepening, he shifted restlessly.

The clock in the corner ticked relentlessly on; when it struck one, he drained his glass. Grimacing, he stood.

They couldn't go on like this. The pain he had seen in her face that morning was etched in his mind; her misery lay like a lead weight around his heart. If she needed some more formidable declaration, then she would have it. He would talk to her privately-and sort the matter out.

He had forgotten what a quick learner she was.

Despite his best endeavours, his next opportunity to speak with Antonia privately occurred the next evening when they took to the floor in the first waltz at Lady Harris's ball. As he drew her into his arms, Philip felt a distinct tremor ripple through her. Drawing her closer still, he deftly swung them into the swirling throng.

"Antonia-"

"Lady Harris's decor is positively inspired, don't you think, my lord? Whoever would have thought of a fairy grotto lined with miniature cannon?"

Philip's lips thinned. "Lord Harris was a naval man- something to do with Ordinance. But I wanted to-''

"Do they fire, do you suppose?" Her features animated, Antonia raised her brows. "I wouldn't think that would be too wise, what with young sprigs like Geoffrey about."

"I doubt anyone else has considered the matter. Antonia-''

"Now there I am sure you are wrong, my lord. I'm perfectly certain the idea of firing one would have occurred to Geoffrey by now."

Philip drew in a slow, steady breath. "Antonia, I want to explain-"

"There is, my lord, absolutely no reason you should." Resolutely, Antonia lifted her chin, her gaze fixed beyond Philip's right shoulder. "There is nothing you have to explain-it is I who should beg your pardon. I assure you such an incident will not occur again. I'm fully conscious of my indiscretion; I assure you there's no reason we need discuss the matter further."

Metaphorically girding her loins, she let her gaze fleetingly touch Philip's face. His expression was hard and distinctly stern.

"Antonia, that's-"

She missed the beat and stumbled.

Philip caught her, steadying her. For an instant, he wondered if she had stumbled on purpose; the startled, darting glances she sent this way and that assured him she had not. "Nobody saw-it was nothing remarkable." He eased his hold once they were circling freely again. “Now-''

"If it is all the same to you, my lord, I suspect I should concentrate on my steps."

Inwardly, Philip swore. The tremor in her voice was entirely genuine. Reining in his impatience, he guided them on through the couples crowding the floor. When next he spoke, his voice was carefully urbane. "I wish to see you privately, Antonia."

She glanced up fleetingly, then looked away. He could feel the quivering tension that held her.

Antonia took a full minute to gather her defences, to ensure her voice was steady when she said, "I believe, my lord, that it would be wisest for us henceforth to follow the conventional paths. In light of our yet-to-be formalised relationship, I would respectfully suggest we should not meet privately until such meetings are customary."

It took every ounce of Philip's savoir-faire to smother his response to that suggestion. To quell the primitive urge that threatened to shatter his social veneer. "Antonia," he said, his voice deadly calm. "If you imagine-"

"Have you seen Lady Hatchcock's new quizzing glass? Hugo said it made her eye big beyond belief."

"I have not the slightest interest in Lady Hatchcock's quizzing glass."

"No?" Antonia opened her eyes wide. "Then perhaps you have heard of the latest on dit. It seems…" She babbled on, barely pausing for breath.

Philip heard the brittleness in her voice; he noted her wide eyes and too-rapid breathing. Frustration mounting, he desisted, only to be forced to listen to her run on without pause until he handed her back into the bosom of her court.

Breathlessly, she thanked him. Philip bestowed upon her a look she should have felt all the way to her bones, then turned on his heel and headed for the cardroom.

He ran her to earth the following afternoon; she had taken refuge in the back parlour, her maid in close attendance.

Antonia looked up as he entered. She was seated at the round table in the centre of the room; thick papers and board, swatches of brocade and silk, ribbons, braids, silk cords and fringes lay scattered across its surface. Her fingers plying a large needle, she was engaged in fastening a circle of brocade over a piece of thick paper.

"Good afternoon, my lord." Blinking in surprise, Antonia succumbed to the temptation to drink in his elegance-then she noticed the gloves he was carrying. "Are you going driving?"

"Indeed." Determinedly languid, Philip halted before the table. "I had wondered, my dear, whether you might care to accompany me? You seem to have been hiding yourself away of late-some fresh air will do you good."

Her gaze fixed safely on his cravat, Antonia blinked again, then looked down. "Unfortunately, my lord, you catch me at an inopportune moment." With a wave of her hand, she indicated the materials spread before her. "I broke my reticule last evening and needs must fashion another to match my gown before Lady Hemminghurst's ball tonight."

"How unfortunate." Philip's polite smile did not waver. "Particularly as I had thought that, perhaps, the day being remarkably calm, I might hand the ribbons to you for a short spell."

Antonia's fingers stilled. Slowly she raised her head until her eyes met Philip's.

Philip hid his triumph; it was the first time since Lady Ardale's unwelcome intrusion into their lives that she had gifted him with one of her wonderfully direct glances.

Then he saw the reproach in her gaze.

"In your phaeton?" she asked.

Philip hesitated, then nodded.

Antonia sighed and looked down. "I have to confess, my lord, that I'm not feeling quite the thing this afternoon-just a mite queasy-I suspect Lady Harris's salmon patties are to blame. So difficult, these days, to be certain of one's salmon." Laying out a piece of silk fringe, she airily continued, "So I'm afraid I must decline your kind-indeed, your very tempting invitation. I really could not trust myself to the rocking of a phaeton." Her face artfully brightening, she glanced upwards, not quite meeting Philip's eyes. "Perhaps if we went in your curricle?"

Philip felt his mask harden, he fought not to narrow his eyes. It was a moment before he replied, his tone determinedly even, "I regret to say I left my curricle at the Manor." A fact he was certain she knew.

Regretfully, Antonia sighed. “In that case, my lord, I fear I must decline your offer." Directing a sweet smile his way, she added, “Do convey my respects to Mr Satterly, should you see him."

Philip looked but she would not meet his eyes again. After a moment's uncomfortable silence, he said, his tone flat, "In that case, my dear, I will bid you a good afternoon." He bowed, the action lacking his customary grace, then swiftly strode from the room.

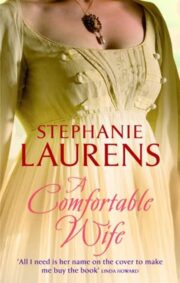

"A Comfortable Wife" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "A Comfortable Wife". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "A Comfortable Wife" друзьям в соцсетях.