They checked out of the Plaza and took the train to Boston, and her parents’ old butler William was waiting at the station for them with one of her parents’ old cars that they still kept in Newport. He began to cry the moment he saw her, and bowed when he met Consuelo, who was very impressed by how old he was, and how respectful to her. And she felt so sorry for him when he cried that she stood on tiptoe to kiss him. He and Annabelle both had damp eyes when they greeted each other. The staff knew about Consuelo from Annabelle’s letters to Blanche, but they were not entirely clear on who her father was or when the marriage had happened. From what they could gather, he had been killed shortly after he and Annabelle were married. William looked at Consuelo with misty eyes and a nostalgic expression.

“She looks just like you at her age. And there’s a little bit of your mother.” He helped them settle into the car, and they set off on the seven-hour drive to Newport, with Consuelo observing and commenting on everything along the way. William explained it all to her. And here again, Annabelle found that much had changed, though not in Newport itself. As they drove into town, it looked as venerable as ever. And Consuelo’s eyes grew wide when she saw the cottage and the vast expanse of land it sat on. It was an imposing estate, and they had kept it in perfect condition.

“It’s almost as big as Grandmother’s house in England,” Consuelo said, in awe of the enormous home, and her mother smiled. It looked just as she had remembered, and brought her back to her own childhood with a sudden pang.

“Not quite,” Annabelle assured Consuelo. “Your grandmother’s house is bigger. But I had some wonderful summers here.” Until the last one. Coming back here brought up so many memories of Josiah, and the terrible end to their marriage. But it made her think of their happier beginnings as well, when she was young and all was hopeful. She was thirty-two years old now, and so much had changed. But it still felt like home to her.

As soon as the car stopped, Blanche and the others came running out of the cottage. She wrapped her arms around Annabelle and couldn’t stop crying. She looked much older, and when she saw Consuelo, she hugged her too. And like William, she told Annabelle that her daughter looked just like her.

“And you’re a doctor now!” Blanche still couldn’t believe it. She could believe even less that she had finally come home. They had thought she never would. And they had been deathly afraid she would sell the house. It was their home too. And they had kept everything in pristine condition for her. It looked as though she had left the day before, not ten years ago. Those ten years seemed like an entire lifetime, and yet when she saw the house again, the time since she’d last seen it melted away to nothing.

It made Annabelle miss her mother again, as she walked past her bedroom. She was staying in one of the guest rooms and had given Consuelo and Brigitte her old nursery for Consuelo to play in. But most of the time, she would be outdoors, as Annabelle had been at her age. She couldn’t wait to take Consuelo swimming, which they did that afternoon.

Annabelle told her that she had learned to swim here, just as Consuelo had learned in Nice and Antibes.

“The water is colder here,” Consuelo commented, but she liked it. She loved playing in the waves, and walking down the beach.

Later that afternoon, when they went back to the house from the beach, Annabelle left her with Brigitte. She wanted to go for a walk by herself. There were some memories she didn’t want to share. She was just leaving the house, when Consuelo came running down the stairs to join her, and Annabelle didn’t have the heart to tell her she couldn’t come. She was so happy there, discovering her mother’s old world, which was so different from the one they lived in now, with their tiny, comfortable house in the sixteenth arrondissement. Everything in her old world seemed huge to her now, and to her child.

The house she had wanted to see was not far, and when she got there she saw that the trees were overgrown, the shutters closed, and it was in disrepair. Blanche had told her it had been sold in the past two years, but it looked like no one lived there, and it hadn’t been used in a decade. It appeared deserted. It was Josiah’s old house, where she had spent her married summers, and where he and Henry had continued their affair, but she didn’t think about that now. She only thought of him. And Consuelo could see that this house had been important to her mother too, although it was small and dark, and looked sad.

“Did you know the people who lived here, Mama?”

“Yes, I did,” Annabelle said softly. She could almost feel him near her as she said the words, and she hoped he was peaceful now. She had long since forgiven him. There was nothing left to forgive. He had done the best he could, and loved her in his own way. And she had loved him too. There was none of the raw disappointment and betrayal she still felt at Antoine’s hands, more recently. The scars of what had happened with Josiah had faded years before.

“Did the people die?” Consuelo asked sadly. It looked that way, judging by the condition of the house.

“Yes, they did.”

“A nice friend?” Consuelo was curious why her mother looked so far away and shaken by being there. And Annabelle hesitated for a long moment. Maybe it was time. She didn’t want to lie about her history to her forever. The lie that she’d been married to Consuelo’s father was enough, and one day she would tell her the truth about that too, not that she’d been raped, but that they hadn’t been married. Now that Lady Winshire had acknowledged her, it wouldn’t be quite as onerous, though still hard to explain.

“This house belonged to a man named Josiah Millbank,” she said quietly, as they peeked into the garden. It was completely overgrown, and looked entirely deserted, which it was. “I was married to him. We got married here in Newport when I was nineteen.” Consuelo looked at her with wide eyes, as they sat down on an old log. “I was married to him for two years, and he was a wonderful man. I loved him very much.” She wanted her to know that part too, not just that it had gone wrong.

“What happened to him?” Consuelo asked in a small voice. So many people had died in her mother’s life. Everyone was gone.

“He got very sick, and he decided that he didn’t want to be married to me anymore. He didn’t think it would be fair to me, because he was so sick. So he went to Mexico, and he divorced me, which means that he ended our marriage.”

“But didn’t you want to be with him even though he was so sick, to take care of him?” She looked shocked, and Annabelle smiled as she nodded.

“Yes, I did. But that wasn’t what he wanted. He thought he was doing a good thing for me, because I was very young. He was a lot older. Old enough to be my father. And he thought I should marry someone else who wasn’t sick and have lots of children.”

“Like my father,” she said proudly, and then a cloud passed her eyes. “But then he died too.” It was all very sad, and made her realize, even at seven, all that her mother had been through, and come out the other end, whole, and alive, and even a doctor.

“Anyway, he divorced me, and went to Mexico.” She didn’t tell her about Henry. She didn’t need to know. “And everyone here was very shocked. They thought he divorced me because I did something wrong. He never told anyone he was sick, and neither did I. So they thought I had done something terrible, and I was very sad. I went to France, and went to work in the war. And then I met your father, and had you. And everyone lived happily ever after,” she said with a smile, as she took Consuelo’s hand in her own. It was a highly edited version, but it was all Consuelo needed to know. And her marriage to Josiah was no longer a secret. It seemed better that way. She didn’t want to keep secrets, or tell lies to cover them anymore. And she had been fair to Josiah in the story. She always had been.

“But why was everyone so mean to you when he went away?” That seemed horrible to Consuelo, and so unfair to her mother.

“Because they didn’t understand. They didn’t know what had really happened. So they told bad stories about it, and about me.”

“Why didn’t you tell them the truth?” That part made no sense to her at all.

“He didn’t want me to. He didn’t want anyone to know he was sick.” Nor why, which was far more understandable. Not to mention the part about Henry Orson.

“That was silly of him,” Consuelo said, glancing over her shoulder at the empty house.

“Yes, it was.”

“Did you ever see him again?”

Annabelle shook her head. “No. He died in Mexico. I was in France by then.”

“Do people know the truth now?” Consuelo asked, still looking pensive. She didn’t like that part of the story at all, when they’d been mean to her mother. She must have been very sad at the time. She even looked sad talking about it now.

“No, they don’t. It’s been a long time,” Annabelle answered.

“Thank you for telling me, Mama,” Consuelo said proudly.

“I was always going to tell you one day, when you were older.”

“I’m sorry they were mean to you,” she said softly. “I hope they won’t be anymore.” The only one who had been recently was Antoine. Not just mean, but cruel. It had been the worst betrayal of all, and had reopened all her old wounds. Talking to Lady Winshire about it had helped her. She saw now what a small, petty person Antoine really was, if he couldn’t love her, even with her past. She wouldn’t have done the same to him. She was a far bigger person.

“It doesn’t matter now. I have you,” Annabelle reassured her, and it was true. Consuelo was all she needed.

They got up and walked back to their cottage then, and for the next three weeks they played and swam and did all the things Annabelle had done as a child and loved there so much.

It was during their last week there that Annabelle took Consuelo to the Newport Country Club for lunch. It was one of the few grown-up things they had done. Other than that, Annabelle had avoided all the places where she might run into old friends. They had stayed mainly on their own grounds, which were large enough. But this one time, they had decided to go out, which was brave of Annabelle.

And just as they were leaving after lunch, Annabelle saw a portly woman walk toward the restaurant. She looked flustered, red-faced, there was a nanny with her, and she was leading six young children and had a baby on her hip. She was snapping at one of them, the baby was crying, and her hat was askew. And it was only when they were inches from each other that Annabelle saw that it was her old friend Hortie. Both of them were shocked and stopped walking, and stood staring at each other.

“Oh… what are you doing here?” Hortie said as though Annabelle didn’t belong there. And then she tried to cover the awkward moment with a nervous smile. Consuelo was frowning, looking at her. Hortie hadn’t even noticed her, she was just staring at her mother as if she’d seen a ghost.

“I’m here with my daughter for a visit.” Annabelle smiled at Hortie, feeling sorry for her. “I see the baby factory is still producing,” she teased her. Hortie rolled her eyes and groaned, and for an instant looked like the friend Annabelle had loved so dearly, and would never have abandoned.

“You’re remarried?” Hortie asked with interest, and then glanced at Consuelo.

“Widowed.”

“And she’s a doctor,” Consuelo piped up proudly, as both women laughed.

“Is that true?” Hortie looked at Annabelle, impressed if it was, but she knew that Annabelle had loved medical things as a young girl.

“It is. We live in Paris.”

“So I heard. I was told you were some kind of hero during the war.”

Annabelle laughed. “Hardly. I was a medic, riding ambulances to field hospitals to pick up wounded men. Nothing very heroic about that.”

“It sounds heroic to me,” Hortie said as her gaggle of children swirled around her, and the nanny tried to keep them in control with little success. Hortie didn’t apologize for the betrayal or say she’d missed her, but you could see it in her eyes. “Will you be here long?” she asked wistfully.

“A few more days.”

But Hortie didn’t ask her to come over, or say she would drop by the Worthington cottage. She knew that James would never have allowed it. He thought Annabelle would be a bad influence on her. Divorcées and adulteresses were not welcome in his home, although the stories about him had been far worse.

For a minute, Annabelle wanted to tell her that she’d missed her, but she didn’t dare. It was too late for both of them. And seeing her had made her sad. Hortie looked blowsy, tired, and overwhelmed, and wasn’t aging well. The pretty young girl she’d been years before was gone. She had become a middle-aged woman with a flock of children, and had turned on her best friend. Annabelle would miss her always. Running into her was like seeing a ghost. They said good-bye without embracing, and Annabelle was quiet as they left the restaurant.

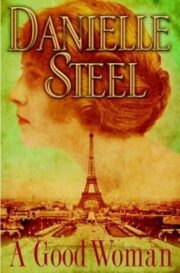

"A Good Woman" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "A Good Woman". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "A Good Woman" друзьям в соцсетях.