"Why is he going in there?" Jenny cried, remembering that Friar Gregory had said he was alone in the priory today. "He can be no threat to you. He said himself he was only stopping at the priory on a journey."

"Shut up," he snapped, and climbed up behind her.

The next hour was a blur, punctuated only by the pounding of the horse against Jenny's backside as they galloped headlong down the muddy road. As they neared a fork in the road, Royce suddenly reined the big horse into the woods and then stopped, as if waiting for something. A few minutes passed and then a few more, while Jenny peered down the road, wondering why they were waiting. And then she saw it: galloping toward them at a breakneck pace came Arik, his outstretched hand holding the reins of the spare horse, which was running beside him. And bouncing and jouncing upon the animal's back as if he'd never ridden before, hanging onto the pommel for his very life was-Friar Gregory.

Jenny gaped at the rather comic spectacle, unable to believe her own eyes until Friar Gregory was so close she could actually see the stricken expression on his face. Rounding on her husband, sputtering in her furious indignation, she burst out, "You-you madman! You've stolen a priest this time! You've actually done it! You've stolen a priest right out of a holy priory!"

Transferring his gaze from the riders to her, Royce regarded her in bland silence, his utter lack of concern only adding to her outrage. "They'll hang you for this!" Jenny prophesied with furious glee. "The pope himself will make sure of it! They'll behead you, they'll draw and quarter you, they'll hang your head from a pike and feed your entrails to-"

"Please," Royce drawled in exaggerated horror, "you will give me nightmares."

His ability to mock his fate and ignore his crime was more than Jenny could bear. Her voice dropped to a strangled whisper, and she stared over her shoulder at him as if he was some curious, inhuman being beyond her comprehension. "Is there no limit to what you will dare?"

"No," he said. "No limit whatsoever." Jerking on the reins he turned Zeus into the road and spurred him forward just as Arik and Friar Gregory galloped abreast. Tearing her eyes from Royce's granite features, Jenny clutched at Zeus's flying mane and glanced sympathetically at poor Friar Gregory, who bounced past, his fear-widened eyes clinging to her in mute appeal and terrified misery.

They kept up the breakneck pace until nightfall, stopping only long enough to rest the horses periodically and give them water. By the time Royce finally signaled Arik to stop, and a suitable camp had been found in a small glade deep within the protection of the forest, Jenny was limp with exhaustion. The rain had stopped earlier that morning, and a watery sun had put in its appearance, and then shone with a vengeance, causing steam to rise from the valleys and adding tenfold to Jenny's discomfort in her damp, heavy velvet gown.

With a tired grimace, she tramped out of the thicket she'd used to shield herself from the men so that she could attend to her personal needs. Raking her fingers through her hopelessly tangled hair, she trudged over to the fire and sent a murderous glance at Royce, who still looked rested and alert as he knelt on one knee, tossing logs onto the fire he'd built. "I must say," she told his broad back, "if this is the life you've led all these years past, it leaves much to be desired." Jenny expected no answer, nor did she receive one, and she began to understand why Aunt Elinor, who'd been deprived of human companionship for twenty years, had missed it so much that now she eagerly chattered away at anyone she could find to listen to her-willingly or no. After an entire night and day of Royce's silence, she was desperate to vent her ire on him.

Too exhausted to stand, Jenny sank down onto a pile of leaves a few paces from the fire, reveling in the opportunity to sit upon something soft, something that didn't lurch and bump and jar her teeth, even though it was damp. Drawing her legs up to her chest, she wrapped her arms around them. "On the other hand," she said, continuing her one-way conversation with his back, "perhaps you find much pleasure in galloping through the woods, ducking tree limbs, and fleeing for your life. And, when that becomes tedious, you can always divert yourself with a siege or a bloody battle, or an abduction of helpless, innocent people. 'Tis truly a perfect existence for a man like you!"

Over his shoulder, Royce glanced at her and saw her sitting with her chin perched upon her knees, her delicate brows raised in challenge, and could not believe her daring. After everything he'd put her through in the past twenty-four hours, Jennifer Merrick-no, he corrected himself, Jennifer Westmoreland-could still calmly sit on a pile of leaves and mock him.

Jenny would have said more, but just then poor Friar Gregory staggered out of the woods, saw her, and stumbled over to sink gingerly onto the leaves beside her. Once sitting, he shifted experimentally from one hip to the other, wincing. "I-" he began, and winced again-"have not ridden much," he admitted ruefully.

It dawned on Jenny that his entire body must be racked with aches and pains, and she managed to smile at him in helpless sympathy. Next it occurred to her that the poor friar was a prisoner of a man with a reputation for unspeakable brutality, and she sought to allay his inevitable fears as best she could, given her animosity for the man who'd captured them both. "I do not think he will murder you or torture you," she began, and the friar looked at her askance.

"I have already been tortured to the full limits, by that horse," he stated dryly, then he sobered. "However, I shouldn't think I'll be killed. 'Twould be foolhardy, and I don't think your husband is a fool. Reckless, yes. Foolish, no."

"Then you aren't concerned for your life?" Jenny asked, studying the friar with new respect as she recalled her own terror at her first sight of the Black Wolf.

Friar Gregory shook his head. "From the three words that blond giant over there allotted me, I gather that I'm to be taken with you to bear witness to the inevitable inquiry that is bound to take place on the matter of whether you are well and truly married. You see," he admitted ruefully, "As I explained to you at the priory, I was merely a visitor there; the prior himself and all the friars having gone into a nearby village to minister to the poor in spirit. Had I left on the morn, as I meant to do, there would have been no one to attest to the vows you spoke."

A brief flair of blazing anger pierced Jenny's weary mind. "If he"-she glanced furiously at her husband, who was near the fire, his knee bent as he tossed more logs onto the blaze-"wanted witnesses to the marriage, he had only to leave me in peace and wait until today when Friar Benedict would have married us."

"Yes, I know, and it seems odd he didn't do that. 'Tis known from England to Scotland that he was reluctant, no, violently opposed, to the idea of wedding you."

Shame made Jenny look away, feigning interest in the wet leaves beside her as she traced her finger on their veined surface. Beside her, Friar Gregory said gently, "I speak plainly to you, because I sensed from our first meeting at the priory that you are not fainthearted and would prefer to know the truth."

Jenny swallowed the lump of humiliation in her throat and nodded, cringing inside at the realization that everyone of importance in two countries evidently knew she was an unwanted bride. Moreover an unvirginal one. She felt unclean and humiliated beyond words-humbled and brought to her knees before the populace of two entire countries. Angrily she said, "I don't think his actions of the past two days will go unpunished. He snatched me from my bed and hauled me out a tower window and down a rope. Now he's snatched you! I think the MacPherson and all the other clans may well break the truce and attack him!" she said with morbid satisfaction.

"Oh, I doubt there'll be much in the way of official retaliation; 'tis said Henry commanded him to wed you posthaste. Lord Westmoreland-er-his grace, has certainly complied with that, although there's bound to be a bit of an outcry from James to Henry over the way he did it. However, at least in theory, the duke obeyed Henry to the letter, so perhaps Henry will be merely amused by all this."

Jenny looked at him in humiliated fury. "Amused!"

"Possibly," Friar Gregory said. "For, like the Wolf, Henry has technically fulfilled the agreement he made with James to the very letter. His vassal, the duke, has wed you, and wed you with all haste. And in the process, he evidently breached your castle, which was doubtlessly heavily guarded, and snatched you right from your family's midst. Yes," he continued more to himself than to her, as if impartially considering a question of dogmatic theory, "I can see that the English may find all this highly entertaining."

Bile surged in Jenny's throat, almost choking her as she recalled all that had happened last night in the hall, and realized the priest was right. The hated English had been wagering amongst themselves, actually wagering in the hall at Merrick, that her husband would soon bring her to her knees, while her kinsmen could do naught but look at her-look at her with their proud, set faces, as they bore her shame as their own. But they were hoping, depending upon her, to redeem herself and all of them by never yielding.

"Although," Friar Gregory said more to himself than to her, "I cannot ken why he would have put himself to such risk and trouble."

"He raves about some plot," Jenny said in a suffocated whisper. "How do you know so much about us-about everything that's been happening?"

"News of famous people flies from castle to castle often with surprising speed. As a friar of Saint Dominic, 'tis my duty and my privilege to go among our Lord's people on foot," he emphasized wryly. "Whilst my time is spent among the poor, the poor live in villages. And where there are villages, there are castles; news filters down from lord's solar to villein's hut-particularly when that news concerns a man who is a legend, like the Wolf."

"So my shame is known to all," Jenny said chokily.

" 'Tis not a secret," he admitted. "But neither is it your shame, to my thinking. You mustn't blame yourself for-" Friar Gregory saw her piteous expression and was instantly consumed with contrition. "My dear child, I beg your forgiveness. Instead of talking to you about forgiveness and peace, I'm discussing shame and causing bitterness."

"You've no need to apologize," Jenny said in a shaky voice. "After all, you, too have been taken captive by that-that monster-forced, dragged from your priory, as I was dragged from my bed, and-"

"Now, now," he soothed, sensing she was teetering between hysteria and exhaustion, "I wouldn't say I was taken captive. Not really. Nor dragged from the priory. It was more a matter that I was invited to come along by the most enormous man I've ever beheld, who also happens to carry a war axe in his belt with a handle nearly the size of a tree trunk. So when he graciously thundered, 'Come. No harm,' I accepted his invitation without delay."

"I hate him, too!" Jenny cried softly, watching Arik stroll out of the woods holding two plump rabbits he'd beheaded with a throw of his axe.

"Really?" Friar Gregory looked nonplused and fascinated. " 'Tis hard to hate a man who doesn't speak. Is he always so stingy with words?"

"Yes!" Jenny said vengefully. "All he nee-needs to do"-the tears she was fighting to hold back clogged her voice-"is look at y-you with those freezing cold blue eyes of his and you j-just know what he wants you to do, and y-you d-do it, because he's a m-monster, too." Friar Gregory put his arm around her shoulders and Jenny, who was more accustomed to adversity than sympathy, especially of late, turned her face into his sleeve. "I hate him!" she cried brokenly, heedless of Friar Gregory's warning squeeze on her arm. "I hate him, I hate him!"

Fighting for control, she moved away from him. As she did so, her eyes riveted on the pair of black boots planted firmly in front of her, and she followed them the full distance up Royce's muscled legs and thighs, his narrow waist and wide chest, until she finally met his hooded gaze. "I hate you," she said straight to his face.

Royce studied her in impassive silence, then he transferred his contemptuous gaze to the friar. Sarcastically, he asked, "Tending to your flock, Friar? Preaching love and forgiveness?"

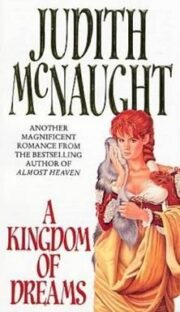

"A Kingdom of Dreams" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "A Kingdom of Dreams". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "A Kingdom of Dreams" друзьям в соцсетях.