He’d run off for a tryst. Of course! What else would have taken him from the palace on this day? What else would see him return to the palace looking as if he’d fallen out of bed and right into his clothes? Were men so desperately sexual all the time?

A loud rap on the door was followed by it swinging open, and Beck strolled in. He paused just inside the doorway and stared at the two of them. “I had hoped that someone might have come and whisked you both down to the ball you’re determined to attend and thus spare me the deed. Alas, I see my dreams have been dashed.”

“A splendid good evening to you, as well, Beck,” Hollis said cheerily.

“My lord is customary, Hollis, but I’ll allow it in light of your obvious delirium of happiness at your sister’s nuptials.”

“Where have you been?” Caroline demanded. “I’ve been waiting and waiting.”

“What are you talking about? I was giving you ample time to admire yourself in the mirror,” he said. “Are you ready?”

“Is it not obvious? I’ve been ready. We both have. You were expected a half hour ago.” She checked her hair in the mirror once more.

“I beg your pardon, but I was out with my Alucian friends. Cheerful lot, I must say. What has happened to the bodice of your gown, Caro? It looks to have gone missing.”

“You were with friends?” Caroline said, arching one brow, hoping to skim over the fact that her bodice had indeed gone missing, and moreover, she didn’t intend to look for it. “What friends? Of which gender?”

“One of two possibilities. Is that another new gown?”

She rolled her eyes at him. “How can you even ask? Of course it is—I couldn’t wear anything that I’ve already worn, not to tonight’s ball. Even you know that.”

“Do you think our funds flow from a bottomless well?” he asked crossly as he dropped into a seat. “You buy gowns as if they cost nothing.”

“Pardon, but wasn’t it you who purchased an Alucian racehorse just last week, Beck?” Hollis asked as she closed her notebook. “You buy horses as if they cost nothing.”

Beck pointed a finger at her. “You are not allowed to offer any opinion or observation just now. Did no one ever tell you to mind your own business?”

Hollis laughed. “Many times. But be forewarned—if I’m not allowed to speak my observations, then I shall write them.”

To the casual observer, this behavior between Hollis and Beck might have been deemed alarmingly impolite, but Beck had known Hollis and Eliza as long as he’d known Caroline. They were family, really. For years, Eliza and Hollis had summered with them at the Hawke country estate. Caroline was a frequent visitor to the home of Justice Tricklebank, their widowed father, who treated her like one of his own. And when their mothers, the best of friends, had died of cholera—Caroline’s mother succumbing after caring for Hollis and Eliza’s mother—Beck had treated Eliza and Hollis as if they were his wards, too.

In other words, he paid them no heed most of the time, and they paid him even less.

Beck stacked his feet on an ottoman. “I’m exhausted. All of this wedding business has taken its toll. I could sleep for days—”

“No, no, no,” Caroline said quickly. “You mustn’t make yourself comfortable, Beck. We’re already late! We must carry on to the ball—it would be the height of inconsiderate behavior to arrive after the newlyweds. You, too, Hollis. It’s time to go.”

“Just a moment,” Hollis said. “I’m making note about the purchase of a racehorse.” She glanced at Beck sidelong.

“Am I never allowed any peace?” Beck groaned. “For God’s sake, then, come on, the two of you. What joy I will experience when you’re both married and I may be relieved of my never-ending duty to escort you about town.”

“What an absurd thing to say,” Caroline said as she checked her headdress one last time. “We are the very reason you are able to attend these events without looking as if you haven’t a friend in the world. You need us, Beck.”

“What I need is silence and a bed,” he said blithely as he offered one arm to Caroline and the other to Hollis. “Let’s get this over and done, shall we, ladies?”

“Oh, Beck, how charming you are,” Hollis said dreamily. “Just when I think I despise you, I discover I love you all over again.”

WHEN LORD HAWKE and his charges had been announced and had entered the crowded ballroom, Caroline looked around for Prince Leopold. Naturally, after his afternoon of debauchery, he was nowhere to be seen.

She was inexplicably exasperated by his absence. Should he not have been here, in the center of attention, doing his duty as brother of the groom? Prince Sebastian and Eliza were due to arrive at any moment, but his brother couldn’t be bothered to arrive in time?

And why had he come into the private wing of the palace looking as if he’d been wrestling? The king and queen were here, as were a variety of Alucian nobility Caroline had met in the month she’d been in Helenamar.

Well, no matter—Caroline didn’t care a whit. Whenever he did deign to make his appearance, she was quite confident that her stunning dress and her obvious appeal would catch his eye. By then, of course, it would to be too late for him. By then she would be surrounded by admiring gentlemen and have no room for him on her dance card. Being admired was her forte, after all.

She checked her train to make sure it was securely fastened and sallied forth to meet all the gentlemen.

CHAPTER FIVE

With all the excitement of a very grand royal wedding, most would be content to come away with the experience of it. But for the families of several young women, the royal wedding ball was a perfect opportunity to begin talks of a new royal wedding. Alas, while Prince Leopold was seen dancing with no less than a dozen such young women, it is common knowledge that an engagement to a Weslorian songbird has all been arranged, and an announcement will soon be made.

This news did not prevent the only remaining bachelor prince in Alucia from departing the ball before anyone else.

—Honeycutt’s Gazette of Fashion and

Domesticity for Ladies

LEO REQUIRED TWO cups of medicinal tea and a cold bath before he began to feel in control of his faculties. He did not feel himself, really—that encounter in the alleyway had left him rattled. From his initial fear of imminent death, to the more insidious fear that someone was plotting against him, to the new fear creeping into his thoughts about what this Lysander fellow needed to say to him, he couldn’t seem to find his footing.

Were there truly spies among them? He had hoped that the cancer had been rooted out after the murder of Matous in London. That the palace had been swept clean of those plotting to overthrow the king. Then again, that sounded awfully naive, to think the palace had been swept clean of plotting and intrigue. Still, plotting and intrigue never had anything to do with him.

What could Lysander possibly want?

As Leo soaked in the bath, he tried to recall the details from the workhouse riots a few years ago. Lysander was a priest from the northern mountains of Alucia that formed the border with Wesloria. He’d come to the capital city, like so many other mountain people, in search of work. According to the reports about him at the time of the riots, he’d found deplorable conditions at the workhouses.

Once, Leo had been riding with friends through the streets of Helenamar. They had happened upon the man standing on an overturned crate, shouting at a crowd of people who gave him their rapt attention. “People are dying!” he’d bellowed. “The people in the workhouses lack clean water and decent food!”

“Did he say workhouse or whorehouse?” Edoard, one of Leo’s companions, had quipped. Their friends had laughed. Leo had not laughed. He’d wondered if what the man said was true.

He’d been intrigued by the mountain of a man with the unruly blond hair, and his courage to rebel about those conditions and thereby risk arrest and detention. “Do you suppose it’s true?” he’d asked his friends.

“No,” Edoard had said immediately. “He wants attention, that’s all.”

“He’s lucky he doesn’t have the attention of the metropolitan police,” Jacques had said.

“If Helenamar is to be the jewel of Europe, can such conditions exist for her residents?” the big man had asked the crowd. “If Alucia is to lead the way in economic development, can she treat the most common of her workers like dogs?”

The crowd was riled and began to chant back at him. Pane er vesi. Pane er vesi. Food and water.

“Will any of the men at the highest reaches of your government listen to a man like me?” he shouted.

“Noo!” the crowd roared back.

Lysander shook his head. “No. But they will listen to all of us.”

“Je, je, je, je!” the crowd began to chant.

“Come,” Edoard had said. “Before it gets out of hand.”

It wasn’t until another fortnight had passed that Leo’s curiosity peaked, and he found a way to have a look at the workhouses himself—incognito. He was completely unprepared and unaware of the conditions in which common people lived. The workhouses—dank, overcrowded and dirty—certainly had not been part of his education. People were suffering without adequate food, clothing or shelter. They were made to work long hours for a meager existence. He’d been incensed on their behalf. He’d been reminded again of how privileged he was. His conscience had been pricked.

He mentioned the conditions to his father one evening during a private meal. “Don’t listen to the false prophets, Leopold. The man wants fame. That’s all.”

Leo had tried to start a conversation with his father about it, but as usual, his father was uninterested in what he had to say. He’d smiled and said, “Worry about your studies, son.”

In the end, it was Leo’s mother who had turned the tide. “I don’t think you should ignore this man,” she said to her husband. “He seems dangerous to me.”

Leo never really knew what had happened after that—he returned to England and his very vibrant social life. But the Alucian Parliament took up the cause, and the workhouses were eventually shut down. Now factories provided modest housing for the workers.

By the end of his bath, Leo had determined it didn’t matter what Lysander wanted—Leo wouldn’t involve himself with it. He wouldn’t be in the garden tomorrow, because Leo was setting sail in two nights, no matter what.

There was a soft rap at the door, and then Leo’s valet, Freddar, appeared, holding a large towel. “Will you dress now, Your Highness?”

Leo sighed. “Je.” He couldn’t avoid the ball. All eyes would be on Leo tonight, more so than ever before. He was the new prized bull, the one everyone wanted as sire. For years, he’d watched Bas endure these evenings and the endless introductions to all manner of women—short and round, tall and thin. Beautiful and plain. Women with pleasing dispositions and those who were cold as fish. All of them wanting an opportunity to woo a crown prince. Leo was no crown prince, but as of today, he was the next best thing. It hardly mattered that his father had already negotiated a marriage—the wealthy and privileged would present their daughters and sisters to him like gifts from the Magi.

His long black formal frock was embellished with the dignitatis epaulets on the shoulders, denoting his rank in the military. A rank that was achieved by virtue of his birth and nothing else. He would also wear a royal blue sash onto which medals of his family’s name, military achievements and honors would be affixed. None of them belonged to him personally.

Those medals would complement the larger, ribboned medals that were pinned to his chest, also granted because of his titles and privileges and for nothing that he’d done. Such as the large bloom of white ribbon with a gold circle and pearls encrusted in the middle, the Order of the King’s Garter. There were more medals that signified his rank in the navy and the army—bestowed on him because he was a prince—as well as the Order of Merit and the Order of the Reeve, given to him by his father. And of course, his father’s coronation medal, another large gold piece with dark blue and gold ribbons, that celebrated Leo’s royal birth.

He was doused in the symbols and trappings of his family’s wealth and privilege, and he’d done absolutely nothing to deserve any of it. How was it fair that by virtue of his birth alone he should have such fortune? How was it fair that another child, born into lesser circumstances, would struggle through his or her life and accomplish far more than Leo ever would, yet not have a single medal worth so much? Any one of these medals on his chest would bring prosperity to a family for several years.

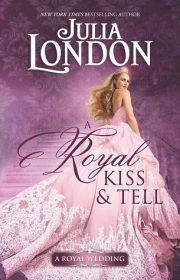

"A Royal Kiss and Tell" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "A Royal Kiss and Tell". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "A Royal Kiss and Tell" друзьям в соцсетях.