‘What?’

‘Nothing.’

She got to her feet as Clemmie came back with her brush and a mirror from my dressing table, struggling under the weight.

‘Oh, salon stuff!’ Frankie relieved her of the mirror and hoisted it onto the table. ‘A French pleat, madam, or shall we cut it all short?’

‘All short!’ sang Clemmie, jumping up and down, ecstatic with excitement.

Frankie grinned. ‘Nah, yer mum might notice that. Then again,’ she grimaced and shot me a look, ‘in her state she might not. Here, give me that.’ She took the brush from her. ‘We’re going to go for a pleat, right? And then we’ll give Archie a comb-over.’

My son had yet to collect much hair, but what he had was long, wispy and very much around the edges. Archie beamed and offered her some more cracker, clenched and soggy in his fist. She took it and put it on her tongue, which was pierced.

‘D’you dare me?’

Clemmie nodded. Frankie swallowed. The children roared with laughter, delighted.

‘Don’t underestimate those harpies, though,’ she went on as I turned to go out of the back door. ‘Once they put their heads together, you’re sunk. Trust me, I should know. Oh, and you might want to take your dressing gown off under your coat. They’ll need smelling salts if they see that.’ I glanced down to where two inches of pale blue towelling protruded from my navy reefer. ‘Then again, you might not. Personally I like the layered look. But our Jennie’s got ever so bourgeois recently. She’s not so into the Quentin Crisp philosophy.’

I took her advice, removed the dressing gown, replaced my coat, and putting one foot in front of the other, went off down the road to choir practice. In a small corner of my mind I was dimly aware that Frankie had given me a searching look as I’d left and, for one crazy moment, I’d almost turned and shared with her. Almost come back in, shut the door and blurted out my troubles, just as she’d blurted hers. I hadn’t, though. Of course not. Because there was no one I could tell. Not even Jennie. Not because I’d be mortified – I would – but because once it was out, I’d have no control over it. Dan would know. Then someone in the pub would know. And my children, so damaged already, must never know. Never hear from someone at school. I clenched my fists fiercely in my coat pockets in resolve. It must be a closely guarded secret. My secret. No one must ever know that their father, my husband, hadn’t found me enough, emotionally. That he’d had another life with another woman. That she’d been to see me ten days ago, paid me a visit. That she’d been there at his funeral and I’d never known. Been in our lives and I’d never known. Filled a void in Phil’s life I hadn’t been able to. They must never know that their father had been unhappy, desperate. It was my shame and I must bear it alone. Tears fled down my cheeks, soaking my face as I walked on.

5

Carefully wiping my face as I stood on the church step, I gave myself a moment; breathed in and out deeply. Then I pushed open the heavy door. The choir were already assembled in their stalls up by the altar, but then I was ten minutes late, having lingered to talk to Frankie. Most people I knew: friends and neighbours, who turned and smiled as I came in. But as I let the heavy oak door swing shut behind me, I wondered what on earth I was doing here. I hadn’t been in since Phil’s funeral and the familiar smell of cold stone, candle wax and damp, which I usually found rather comforting, seemed to ambush my senses as if a hood had been slipped stealthily over my head. I felt even more breathless than usual. I turned and with a shaky hand reached for the door handle again. I could pretend I’d forgotten something, then not come back. But the handle was stiff, and anyway, Jennie was beside me in a moment, having slipped out of her stall and down the aisle. My arm was in her vice-like grip.

‘Good, good, you’re here,’ she purred. ‘We haven’t started yet because we’re waiting for the organist. Come along, I’ve saved you a place.’

She frogmarched me down the aisle in seconds, which wasn’t hard, because our church is tiny. And rather beautiful, or so I usually thought. This evening, though, the domed ceiling with its rows of blackened beams seemed ominously lofty and towering; the figure in the stained-glass window, St John the Baptist, I think, less kindly and benevolent, more threatening as he turned to glare at me over his rippling shoulder in his rags, eyes flashing. Angie was beckoning hard from the back row. No Peggy, but then she was a firm non-believer.

‘Papist nonsense.’

‘It’s C of E, Peggy.’

‘Still. All those smells and bells.’

‘Not in the Anglican church.’

‘I’ve got my own, thank you very much.’ And she’d puff on her ciggie and tinkle her beads.

‘Hello, Poppy.’

Molly, a widow of about seventy, was sitting in the front row with her carer. She looked a bit dishevelled and smiled toothlessly at me, most of her tea down her front, shaky paws, slippers on. Molly wasn’t quite like other budgerigars.

‘Hello, Molly.’

‘Would you like to sit beside me, dear?’

‘Of course.’ I moved to do so.

‘No – no, because Angie and I have saved you a place, haven’t we?’ Jennie’s grip tightened on my arm and she shot me, then Molly, a look.

But, actually, I had a feeling I didn’t necessarily want to be squeezed between my two best friends tonight. And anyway, Molly would be hurt. I sat firmly where I was. Jennie hesitated – I think for a moment considering heaving me bodily to my feet and bundling me away – then she rolled her eyes, shrugged helplessly at Angie, who rolled her eyes back, and sat huffily beside me, which put her next to Jed Carter, a local farmer from down the valley. Molly wasn’t the only one with an appendage this evening. Jed didn’t go anywhere without his sheepdog, Spod, a randy old boy lying at his feet who was in love with Leila. The joy in Spod’s eyes as he sniffed Jennie’s ankle, got a whiff of his beloved and realized he could shut his eyes and pretend her left leg was Leila, was hard to describe.

‘You see why we don’t sit here?’ hissed Jennie as Spod attached himself to her like a limpet, eyes glazed, humping hard. She shook him off furiously.

‘Sorry.’

‘And Spod’s not the only reason, as you’ll discover to your cost,’ she muttered grimly, as Sue Lomax, flaxen and inclined to furious blushes, took up her position at the lectern, tapping it smartly for our attention. We obediently got to our feet. Sue, or Saintly Sue as she was surreptitiously known, was attractive in a buxom way, but preachy. Ex-head girl, county lacrosse player and choir mistress, Sue was an all-round goody-goody – although Jennie and I privately thought her frustrated and man-hungry. She cleared her throat and looked important.

‘Right. Welcome, everyone. Now since you’re all here I think we’ll crack on with just Ron on the piano because Mr Chambers has just sent me a text saying he’ll be a bit late.’ She gazed down at the phone in her hand with a look I’d seen very recently in someone else’s eyes. Ah yes, Spod’s.

‘The organist,’ Jennie informed me importantly.

So crack on we did, straight into Mozart’s Gloria, with Just Ron, who played mostly at the pub, thumping away valiantly. Everyone belted it out, myself included surprisingly, bounced as I was into behaving, into opening my mouth and remembering it from school. It was quite a shock, and not altogether unpleasant. I even felt a sensation approaching the warmth of blood in my veins. Molly was a bit distracting beside me, though, because she was singing something different.

‘She’s singing “Nights in White Satin”,’ I muttered to Jennie when Sue tapped the lectern to stop us because Ron had lost his place.

‘Always does,’ muttered back Jennie. ‘But she’s been in the choir for thirty years, so what can you do? We just don’t sit next to her,’ she added pointedly.

At that moment the church door flew open.

‘Oh, good – you made it, Luke!’ Saintly Sue swung around delighted, even more flushed than usual and her colour was always high.

A tall, rather attractive sandy-haired man in jeans, a biscuit-coloured linen jacket and gold-rimmed specs bounded down the aisle.

‘New organist,’ Angie leaned forward from behind to murmur in my ear, as we lunged to catch our hymn sheets, which were fluttering up like a flock of doves on the blast of cold air.

‘Sorry I’m late,’ he said, bouncing towards us with a wide smile. ‘Bit of a cock-up at work and I couldn’t get away.’ There was a definite puppyish charm: long legs, floppy hair, eyes that glinted merrily from behind the specs in an open, friendly face.

‘Oh, no, not at all,’ purred Sue, smoothing back her hair and straightening her blue lambswool jumper over her ample bosom. ‘We were slightly early in fact. But then I’m always a bit keen!’

It might not have been entirely what she meant to say – Jennie sniggered – but I find that often happens to me, and as her hand went to her darkening throat, I sympathized.

‘Well, I’ll pop up, shall I?’ Luke said, after a slight pause during which their eyes met, his slightly more amused than hers. He indicated the organ above us, aloft. ‘Press on?’

‘Oh, yes, do,’ said Sue, as if it was a terrific idea, and one that hadn’t occurred to her. ‘Super!’

‘You’re all sounding great, by the way,’ he told us. ‘I could hear you halfway down the street – wonderful stuff!’

He bestowed on us another winning smile, gathering everyone in, and everyone beamed delightedly back. All except one. I might have remembered how to do the Gloria, but I wasn’t up to beaming yet. My mouth did twitch politely, but later, after the event, as I find is often the case these days.

‘Rather gorgeous, isn’t he?’ breathed Jennie lustily in my ear as Luke eased himself into position at the organ. He had a lengthy grace, sensitive fingers poised.

‘Not bad,’ I said non-committally.

‘He’s fresh out of the Guildhall,’ Angie billowed from behind into my other ear, as if he were a gleaming trout from the river. ‘Post-grad, obviously. Just bought a cottage in Wessington. He’s in insurance now. Got his own business.’

I didn’t answer.

‘Incredibly charming,’ she murmured again. ‘I mean, to talk to.’ As opposed to what?

‘All yours, Angie,’ I said, turning and managing the first half-smile of the evening. ‘I’ll hold your handbag.’

‘Me?’ She reared back incredulously, hand on heart. ‘Oh, no, he’s far too young for me. He’s your age, Poppy.’ She fluttered her fingers dismissively at me.

I turned back. Shut my eyes. Why had I come? Why wasn’t I at home in my chair?

Off we went again, only this time not so successfully. As Ron slipped gratefully out of the side door and back to his pint in the Rose and Crown, Luke, up at the organ, got very busy. So busy we didn’t know where we were. All sorts of crashing introductory chords rolled into one another like waves and we’d ejaculate prematurely only to discover Luke was still building up to something big. Only Molly ploughed on doggedly with her shrill, warbling rendition of the number-one seventies hit for Procol Harum. Molly, and obviously Spod, whose look of glazed lust as Jennie tried to concentrate and forgot to kick him off was close to euphoric. As the organ threatened to climax, Spod, it seemed, was closer.

Afterwards, as we walked home, or rather as I was escorted, my friends agreed over my head that we needed more practice.

‘Which is fine, because we’ve got plenty of time. The wedding’s not for a few weeks,’ said Jennie.

‘Wedding?’ I was surprised to hear my voice.

‘Well, that’s the whole point, that’s what we’re practising for.’

‘Oh.’

‘Every Monday,’ Angie told me firmly. ‘And don’t forget, you’re all coming to my house tomorrow.’

‘Are we?’ I felt panicky. ‘Why?’

‘Because we’re starting the book club. We told you that a week or so ago, remember?’

Oh, yes, vaguely. But it had been that terrible day. The one when everything had changed. All the clocks stopped. Black Friday. When, suddenly, I hadn’t been a widow who was finding hidden reserves and coping really rather marvellously, much to the relief of my friends, but in the blink of an eye, in twenty-five minutes to be precise, had become someone different.

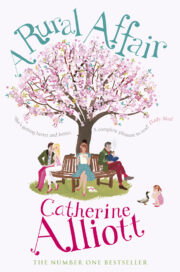

"A Rural Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "A Rural Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "A Rural Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.