The scent of new bamboo was in the air, and off in the distance, a pair of snow white egrets soared into the blue sky. I sighed with pleasure, dazzled. I was so entranced in my own visions of the rolling lawns, the flagstone walkways, the flower beds and bushes, that I didn't hear a car come up our drive, nor did I hear the door chimes.

James came out to the patio to inform me I had a visitor. Before I could go back into the house, Paul's father appeared. As soon as James retreated, Octavious hurriedly approach me. A chilling shiver ran down my spine.

"I told Paul I'd join you two for lunch and then go over to the wells with him, but I left early so I would have a chance to speak with you alone," he quickly explained.

"Mr. Tate . . ."

"You might as well start calling me Octavious or . . . Dad," he said, not quite bitterly, but not quite willingly either.

"Octavious, I know this is something you left my house believing I wouldn't go through with, but Paul was so heartbroken―and after I had been attacked by Buster Trahaw—"

"Don't explain," he said. He took a deep breath and gazed out at the swamp. "What's done is done. Long ago," he continued, "I stopped believing that Fate or Destiny owes me anything. Whatever good fortune I have, whatever blessings I receive, I don't deserve. I live only to see my children and my wife happy and secure."

"Paul is very happy," I said.

"I know. But my wife . . ." He looked down a moment and then raised his dark, sad eyes to me. "First off, she's terrified that somehow, because of this marriage, the truth will rear its ugly head in our small community and all of the make-believe she has constructed around Paul and herself will come crashing down. People think because we are a rich, successful family that we are as hard as rock, but behind closed doors . . . our tears are just as salty."

"I understand," I said.

"Do you?" He brightened. "Because I've come early to beg a favor."

"Of course," I said without hearing his request.

"I want you to keep the . . . for lack of a better word . . . illusion alive whenever you see her. Even though you know the truth and Gladys knows you know."

"You didn't have to ask me," I said. "I'd do it for Paul as well as for Mrs. Tate."

"Thank you," he said with relief, and then gazed around. "Well, this is quite a home Paul is building. He's a nice young man. He deserves his happiness. I'm very proud of him, always have been, and I know your mother would have been proud of him, too." He backed away. "Well . . . I . . . I'm just going out to speak to one of the workers in front," he stammered. "I'll wait for Paul. Thanks," he added, and quickly turned to disappear into the house.

My quickened heartbeat slowed, but the emptiness in my stomach that made it feel as if I had swallowed a dozen butterflies live continued. It would take time, I thought, and maybe even time wouldn't smooth the rough edges between me and Paul's parents, but for Paul's sake, I would try. Every day of this specially arranged marriage would be a day full of tests and questions. At least in the beginning. Despite all we had and all we would have, I had to question whether or not I could go through with it.

James returned to interrupt my heavy thoughts. "Mr. Tate is on the phone, madame," he said.

"Oh. Thank you, James." I started for the house, realizing I didn't know exactly where the closest phone was.

"You can take it right here on the patio," James said, and nodded toward the table and chairs. A telephone had been placed on a small bamboo stand beside one of the chairs.

"Thank you, James." I laughed to myself. The servants were more familiar with my new home than I was. "Hello, Paul."

"Ruby, I'll be home very soon, but I had to call you to tell you about this stroke of luck. At least, I think it is," he said excitedly.

"What is it?"

"Our foreman here at the cannery knew this nice elderly woman who just lost her job as a nanny because the family's moving away. Her name is Mrs. Flemming. I just spoke to her on the phone and she can come to Cypress Woods this afternoon for a personal interview. I spoke with the family and they can't stop raving about her."

"How old is she?"

"Early sixties. She's been a widow for some time. She has a married daughter who lives in England. She misses her family and seeks employment to be around children. If she works out, maybe we can hire her immediately and leave her with Pearl while we go to New Orleans."

"Oh, I don't know if I can do that so soon, Paul."

"Well, you'll see after you speak with her. Should I tell her to come around two?"

"Okay," I said.

"What's the matter? Aren't you happy about it?" he asked. Even through a telephone, Paul could sense when I was nervous or anxious, sad or happy.

"Yes, it's just that you keep moving so fast, I barely have time to catch my breath over one astounding thing when you present me with another."

He laughed. "That's my plan. To overwhelm you with good things, to drown you in happiness, so that you will never regret what we have done and why we have done it," he said. "Oh, my father is going to join us for lunch. He might arrive before I do, so . . ."

"Don't worry," I said.

"I'll call Mrs. Flemming and then I'll start for home. What's Letty making?"

"I was afraid to ask her," I said, suddenly realizing. He laughed.

"Just tell her you'll put the hoodoo on her if she doesn't behave," he said.

I hung up and sat back. I felt like I was in a pirogue going over one waterfall after another, with no chance to catch my breath.

"The little one's up, Mrs. Tate," Holly called from an upstairs window.

"Coming," I said. There wasn't time to think about anything now, but maybe Paul was right. Maybe that was for the best.

At lunch neither I nor Paul's father did or said anything to reveal we'd spoken earlier, but we were all nervous. Paul did most of the talking. He was so full of excitement, it would have taken a hurricane to slow him down. His conversation with his father finally centered around their business problems.

Promptly at two, Mrs. Flemming arrived in a taxi. Paul's father had left, but Paul had remained to greet her with me. The first thing that struck me about her was how close in size she was to Grandmère Catherine. Standing no taller than five feet three or four, Mrs. Flemming had the same doll-like, diminutive facial features: a button nose and small, delicate mouth with two bright grayish blue eyes. Her light silvery hair still had some strands of corn yellow running through it. She kept it pinned up in a soft bun with her bangs trimmed.

She presented her letter of reference and we all went into the living room to talk. But none of her previous experience, nor an arm's length of references, would have made any difference if Pearl didn't take to her. A baby is completely reliant on its instincts, its feelings, I thought. The moment Mrs. Flemming saw my baby and the moment Pearl set eyes on her, my decision was made. Pearl smiled widely and didn't complain when Mrs. Flemming took her into her arms. It was as if they had known each other from the day Pearl had been born.

"Oh, what a precious little girl," Mrs. Flemming declared. "You are precious, you know, as precious as a pearl. Yes, you are."

Pearl laughed, shifted her eyes toward me as if she wanted to see whether or not I was jealous, and then gazed into Mrs. Flemming's loving face.

"I didn't get much chance to be with my own granddaughter when she was this small," she remarked. "My daughter lives in England, you know. We write to each other a lot and I go there once a year, but . . ."

"Why didn't you move there with her?" I asked. It was a very personal question, and perhaps I shouldn't have asked it so directly, but I felt I had to know as much as I could about the woman who would be with Pearl almost as much as, if not more than, I would be. Mrs. Flemming's eyes darkened.

"Oh, she has her own life now," she said. "I didn't want to interfere." Then she added, "Her husband's mother lives with them."

She didn't have to explain any more. As Grandmère Catherine would say, "Keeping two Grandmères under the same roof peacefully is like trying to keep an alligator in the bathtub."

"Where are you living now?" Paul asked.

"I'm just in a rooming house."

He looked at me, while Mrs. Flemming played with Pearl's tiny fingers.

"Well, I don't see any reason why you shouldn't move right in, then," I said. "If the arrangements are satisfactory for you," I added.

She looked up and brightened immediately.

"Oh yes, dear. Yes. Thank you."

"I'll have one of my men take you back to the rooming house and wait for you to get your things together," Paul said.

"First let me show you where you will sleep, Mrs. Flemming," I said, pointedly eyeing Paul. He was doing it again, moving along so fast, I could barely catch my breath. "Your room adjoins the nursery."

Pearl didn't complain when Mrs. Flemming carried her out and up to her room. I kept feeling there was almost something spiritual about the way the two of them took so quickly to each other, and sure enough, I discovered Mrs. Flemming was left-handed. To Cajuns that meant she could have spiritual powers. Perhaps hers were more subtle, the powers of love, rather than the powers of healing.

"Well?" Paul asked after Mrs. Flemming had left with one of his men to get her things.

"She does seem perfect, Paul."

"Then you won't be upset leaving her here with Pearl?" he followed. "We'll be away only a day or two." I hesitated and he laughed. "It's all right. I've come up with the solution. I have to be reminded from time to time how rich I really am. We really are, I should say."

"What do you mean?"

"We'll just take Pearl along, reserve an adjoining room with a crib," he said. "Why should I care what it costs, as long as it makes you happy?"

"Oh, Paul," I cried. It did seem like his newfound wealth could solve every problem. I threw my arms around him and kissed him on the cheek. His eyes widened with happy surprise. As if I had crossed a forbidden boundary, I pulled back. For a moment my happiness and excitement had overwhelmed me. A strange look of reflection came into his blue eyes.

"It's all right, Ruby," he said quickly. "We can love each other purely, honestly. We're only half brother and sister, you know. There's the other half."

"That's the half that worries me," I confessed softly.

"I just want you to know," he said, taking my hands into his, "that your happiness is all I live for." His face became dark and serious as we just stared into each other's faces.

"I know, Paul," I finally said. "And that frightens me sometimes."

"Why?" he asked with surprise.

"It's . . . it just does," I said.

"All right. Let's not have any sad talk. We have to pack and plan. I have to go make some arrangements with the oil drill foreman and then go back to the cannery for a few hours. In the meantime, draw up your shopping list and don't spare a thing," he said. "My family will be here about six-thirty," he added, and left.

I had forgotten about that. Facing Paul's mother was something I dreaded. It started my heart tripping with anxiety. Despite the promise I had made to Paul's father, I wasn't good at looking someone in the face and ignoring the truth. My twin sister, Gisselle, was the expert when it came to that, not me. Somehow, though, I had to do it.

I changed my dress five times before deciding on the one I would wear to dinner with my new family. I couldn't decide whether I should pin up my hair or wear it long. Every little detail suddenly took on paramount importance. I wanted to make the best impression I could. In the end I decided to pin up my hair and went down to dinner just as the Tates arrived. Paul was already dressed and waiting in the entryway.

Toby and Jeanne entered first, Jeanne bubbling over with excitement and eager to describe how the community was reacting to our elopement. Octavious and Gladys Tate followed; she clung to his arm as if she were afraid she wouldn't be able to stand straight or keep from fainting if she were on her own. She kissed Paul on the cheek and then gazed up at me as I descended the stairway.

A tall woman, only an inch or so shorter than her husband, Gladys Tate usually projected a regal stature. I knew she had come from a wealthy Cajun family in Beaumont, Texas. She had attended a finishing school and college where she had met Octavious Tate. It often surprised me that more people didn't suspect Paul was not really her child. Her features were so much sharper, thinner. There was a hardness in her face, a look of superiority and arrogance, and aloofness, that set her apart from most of the women in our Cajun community, even the ones who were wealthy, too.

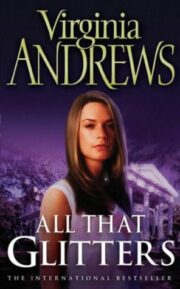

"All That Glitters" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "All That Glitters". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "All That Glitters" друзьям в соцсетях.