"I've got to get back to dinner at the house," Paul said after we pulled up to the dock and he helped us out of the boat. "Uncle John, my mother's brother, is here from Clearwater, Florida, and I promised," he said apologetically.

"It's all right. I'm tired and I want to go to sleep early tonight myself."

"I'll stop by as soon as I can tomorrow. Tonight, if I can get an hour alone with my father, I'll tell him about our decision," he added firmly. My heart began to pitter-patter. It was one thing to talk about all this, but another to actually start the series of events that would make us man and wife.

"I hope it's the right decision, Paul," I said.

"Of course it is. Stop worrying. We'll be very happy," he promised, and leaned over to kiss my cheek. "Besides, God owes us some happiness and success," he added with a smile.

I waved good-bye as he started away in his boat. After I fed Pearl and put her to sleep, I ate a little gumbo, read by the butane lantern, and went to sleep myself, praying for the wisdom to make the right decisions.

Mornings began for me now just the way they had when I had lived here with Grandmère Catherine. After I carried out the blankets, baskets, and palmetto hats I had woven in the loom room, I set Pearl out in her carriage in the shade beside the roadside stand and did some needlework to pass the time and wait for any tourist customers. It was a quiet morning, but I had nearly a half dozen cars stop and sold most of my blankets and baskets by lunch. I had only a few customers for my gumbo, and then the long, quiet, and hot afternoon settled over the bayou. When the insects began to bother Pearl, I decided it was time to take a break and brought her into the shack for her afternoon nap. I had expected Paul to drop by during lunch, but he didn't, and he had still not arrived by midafternoon.

I made myself some cold lemonade and sat on the front gallery just thinking about the past. In my pocket I had crumpled the most recent letter from my twin sister, Gisselle. She was attending a ritzy private college in New Orleans that sounded more like a place to dump spoiled rich young people than a real institute of higher learning. Her teachers, from what she wrote, let her get away with not doing her reading or homework or paying attention in class. She even bragged about how often she cut classes without being reprimanded for doing so.

But in all of her letters she loved to include some news of Beau, and even if it was news that brought me pain, I still had to read it repeatedly. I unfolded the letter and skipped down to those passages. "You might be interested to know," she wrote, knowing how much I wanted to know ". . . that Beau is getting more serious with this girl in Europe. His parents told Daphne that Beau and his French debutante are only inches away from announcing a formal engagement. All they do is rave about her, how beautiful she is, how wealthy she is, and how cultured she is. They said the best thing they could have done for him was to send him to Europe and keep him there.

"Now let me tell you about the boys here at Galen . . ."

I balled the letter in my fist and shoved it back into my pocket. Memories of Beau seemed stronger now that I was thinking about marrying Paul and choosing a safe, secure life. But it promised to be a life without passion, and whenever I thought about that, I thought about Beau. His soft smile appeared before me and I recalled the morning when Gisselle and I were leaving for Greenwood, the private school in Baton Rouge. He had arrived just in time and we had only a few minutes to say our good-byes, but he surprised me by giving me the locket I still wore hidden under my blouse.

I pulled it out and opened it to look at his face and mine. Oh, Beau, I thought, surely I will never love another man as passionately as I loved you, and if I can't have you, then perhaps a happy, secure life with Paul is the right choice. The feel of warm tears on my cheeks surprised me. I wiped them away quickly and sat back just as a familiar big automobile pulled into the yard. It was Paul's father, Octavious. I closed the locket and quickly dropped it back under my blouse where it rested between my breasts.

A tall, distinguished-looking man who was always well dressed and well groomed, Mr. Tate stepped out of his car. His shoulders dipped like a weary old man's and his eyes looked tired. Paul got most of his good looks from his father, who had a strong mouth and jaw with a straight nose, not too long or too narrow. I hadn't seen Mr. Tate for some time and I was a bit surprised at how much he had aged in the interim.

"Afternoon, Ruby," he said when he reached the steps. "I was wondering if I could talk to you sort of privately."

My heart was pounding. I couldn't remember passing more than a half dozen words between us, mostly hellos and good-byes at church over the years.

"Of course," I said, standing. "Come inside. Would you like a glass of lemonade? I just made a fresh pitcher."

"I would. Thanks," he said, and followed me into the house.

"Please, sit down," I said, nodding toward my one good piece of furniture: the rocker.

I poured his glass of lemonade and returned to the living room.

"Thank you," he said, taking the glass, and I sat across from him on the worn, faded brown settee, the threads so thin on the ends of the arms, the stuffing of Spanish moss showed through. He took a sip of the lemonade. "Very good," he said. Then he looked about nervously for a moment and smiled. "You haven't got much here, Ruby, but you keep it real nice."

"Not as nice as Grandmère Catherine used to keep it," I said.

"Your Grandmère was quite a woman. I must confess I never took much stock in faith healing and the herbal medicines she concocted, but I know many people who swore by her. And if anyone could stand up to your Grandpère, it was her," he added.

"I miss her a great deal," I admitted. He nodded and sipped some more lemonade. Then he took a deep breath. "I guess. . . I guess I'm a little nervous. The past has a way of coming back at you and punching you in the stomach when you least expect it sometimes," he added, and leaned forward, his sharp, penetrating gaze fixing on me.

"You're Catherine Landry's granddaughter and you've been through a helluva lot yourself. I can see in your face that you're much older and wiser than the pretty little girl I used to see march up to the church beside her Grandmère."

"The past has punched us both in the stomach," I said. His eyes brightened with more interest.

"Yes. Well then, you'll understand why I don't want to beat around the bush. You know some of what happened in the past and you probably got some ideas about me. I don't blame anyone but myself for that. Twenty-one years ago, I was what you'd call a very young man, full of himself. I'm not here to justify anything or make excuses for myself," he added quickly. "What I did was wrong and I've been paying for it in one way or another all my life.

"But your mother . . . Gabrielle . . . she was one special young woman." He shook his head and smiled with the memory. "Being your Grandmère's daughter and all, I used to think she was one of them swamp goddesses about whom the old folks whispered and most Christian folks half believed in in spite of themselves. Seemed like you could never come upon her, never surprise her without her looking beautiful, so beautiful, it was . . . spiritual. I know it's hard for you to understand about a woman you never set eyes on, but that's the way she was."

Deep in my heart, I felt waves of dread. Why was he telling all this now?

"Every time I set eyes on her," he continued, "my heart would pound and I'd feel like tiptoeing around her. When she looked at me . . . it was like that Greek thing . . . you know with that cherub and his bow and arrow?"

"Cupid?"

"Yeah, Cupid. I was married, but we had no children yet. I tried to love my wife. I did," he said, raising his hand, "but it was as if Gabrielle cast spells or something. One day I was poling through the swamp alone, returning from a little fishing, and I came around a turn and found her swimming without a stitch of clothing. I thought all time had stopped. I froze and held my breath. All I could do was watch her. She had the most youthful, happy eyes, and when she set them on me, she laughed. I couldn't help myself. I peeled off my own clothes as fast as I could and dove into the water. We swam side by side, splashed each other and tormented each other by embracing and breaking away. I followed her out of the water to her canoe and there . . .

"Well, the rest you know. I owned up to what I had done as soon as it was revealed. Your Grandpère Jack came after me.

"Gladys, well, she was devastated, of course. I broke down and cried and begged her to forgive me. In the end she didn't, but she was bigger about it than I thought possible. She decided we would pretend the baby was hers and she began this elaborate ruse, faking her pregnancy.

"Your Grandpère wasn't satisfied with the initial payment. He came after me time after time, demanding more until I finally put an end to it. By then Paul was a little boy and I realized no one would believe any story Jack Landry spun. He stopped bothering me and the whole affair ended.

"Of course, I've spent most of my life ever since trying to make it up to my wife. She never let Paul think she was anything but his mother either, and until the time Paul found out the truth, he never felt anything toward her but a son's love. I'm sure of that. In fact, I go so far as to say he still feels that way toward Gladys. He's just an awfully confused young man sometimes. We've had our arguments about it, and I thought he understood and accepted and finally forgave."

He paused and anxiously, with narrow eyes, waited for me to digest his tale.

"That's a great deal to ask anyone to forgive, especially Paul," I said. His lips grew tight for a moment and then he nodded as if confirming a thought about me.

"I got to tell you," he continued, "when you ran off to New Orleans, I was happy. I thought he would start looking for a nice young lady to be his wife and the turmoil would be over, but . . . you came back, and last night . . . last night he came to me and told me what you two had decided. All the time he was having that mansion built, I feared something like this, but I hoped I was wrong."

He sat back, exhausted for a moment.

"Our plan is to just live together, side by side," I said softly. "So many people around here think Pearl is Paul's child anyway."

"I know. Gladys even feared it herself for a while until Paul explained, but now she's in a deep depression. You see," he said, sitting forward, "we both want only the best for Paul. We want him to have a normal life, to have the things any man should have, especially children of his own. I don't think he realizes what he's proposing to do.

"In short, Ruby, I come here to plead for my son. I come here to ask you to refuse to marry him. There's no need for him to pay for his father's sins. Maybe this one time, the son don't have to have his father's mistakes and pain on his head. We can change it, stop it from happening, if you'll only turn him away. Once you do, he'll settle down and marry some nice young girl and—"

"The last thing in the world I want to do, Mr. Tate, is hurt Paul," I said, the tears streaming down my face. I made no effort to wipe them away and they dripped from my chin.

"I'm really asking for my wife, too. I don't want her hurt anymore. It seems this sin I committed won't die. It's reared its ugly head again to haunt me even twenty-one years later."

He straightened up in his seat. "I'm prepared to offer you some security, Ruby. I can give you what you need until you find yourself another young man and—"

"Don't!" I cried. "Don't offer me a bribe, Mr. Tate. Seems like everyone wants to buy away their troubles in this world, that everyone, whether it's rich Creoles or rich Cajuns, everyone thinks money has the power to right every wrong. I'm doing just fine right now, and soon I will be inheriting money from my father's estate."

"I'm sorry," he said softly. "I just thought . . ."

"I don't want it."

I turned away and a heavy silence fell between us.

"I'm begging you for my son," he said softly. I closed my eyes and tried to swallow, but my throat wouldn't work. It felt as if I had already swallowed a small rock and it was stuck in my chest. I nodded.

"I’ll tell Paul I can't do it," I said, "but I don't know if you understand how much he wants it."

"I understand. I'm prepared to do all I can to help him get over it."

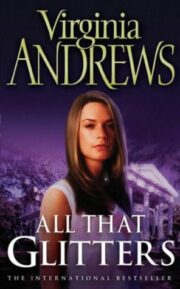

"All That Glitters" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "All That Glitters". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "All That Glitters" друзьям в соцсетях.