"No," said Worth. "I will not."

"Good! You don't mince matters. I like that. Your wife is a famous whip, I believe. For the sake of our approaching kinship, find me a pair such as you would drive yourself, and I will challenge her to a race."

"I have yet to see a pair in this town I would drive myself," replied the Earl.

"Ah! And if you had? I suppose you would not permit Lady Worth to accept my challenge?"

"I am sure he would not," said Judith. "I did once engage in something of that nature - in my wild salad days, you know - and fell under his gravest displeasure. I must decline therefore, for all I should like to accept your challenge."

"Conciliating!" Barbara said with a harsh little laugh. She saw Judith's eyes kindle, and said impulsively: "Now I've made you angry! I am glad! You look splendid just so! I could like you very well, I think."

"I hope you may," Judith replied formally.

"I will; but you must not be forbearing with me, if you please. There! I am behaving abominably, and I meant to be so good!"

She clasped Judith's hand briefly, allowed her a glimpse of her frank smile, and turned from her to greet Lavisse, who was coming towards her across the room.

He looked pale. He came stalking up to Barbara, and stood over her, not offering to take her hand, not even according her a bow. Their eyes were nearly on a level, hers full of mockery, his blazing with anger. He said under his breath: "Is it true, then?"

She chuckled. "This is in the style of a hero of romance, Etienne. It is true!"

"You have engaged yourself to this Colonel Audley? I would not believe!"

"Felicitate me!"

"Never! I do not wish you happy, I! I wish you only regret."

"That's refreshing, at all events."

He saw several pairs of eyes fixed upon him, and with a muttered exclamation clasped Barbara round the waist and swept her into the waltz. His left hand gripped her right one; his arm was hard about her, holding her too close for decorum. "Je't'aime; entends tu, je't'aime!"

"You are out of time," she replied.

"Ah, qu'importe?" he exclaimed. He moderated his steps, however, and said in a quieter tone: "You knew I loved you! This Colonel, what can he be to you?"

"Why, don't you know? A husband!"

"And it is I who love you - yes, en desespere!"

"But I do not remember that you ever offered for this hand of mine, Etienne." She tilted her head back to look at him under the sweep of her lashes. "That gives you to think, eh, my friend? Terrible, that word marriage!"

"Effroyant! Yet I offer it!"

"Too late!"

"I do not believe! What has he, this colonel, that I have not? It is not money! A great position?"

"No!

"Expectations, perhaps?"

"Not even expectations!"

"In the name of God, what then?"

"Nothing!" she answered.

"You do it to tease me! You are not serious, in fact. Listen, little angel, little fool! I will give you a proud name, I will give you wealth, everything that you desire! I will adore you - ah, but worship you!"

She said judicially: "A proud name Charles will give me - if I cared for such stuff! Wealth?Yes, I should like that. Worship! So boring, Etienne, so damnably boring!"

"I could break your neck!" he said.

"Fustian!"

He drew in his breath, but did not speak for several turns. When he unclosed his lips again it was to say in a tone of careful nonchalance: "One becomes dramatic: a pity! Essayons encore! When is it to be, this marriage?"

"Oh, confound you, is not a betrothal enough for one day? Are we not agreed that there is something terrible about that word marriage?"

His brows rose. "So! I am well content. Play the game out, amuse yourself with this so gallant colonel; in the end you will marry me."

A gleam shot into her eyes. "A bet! What will you stake - gamester?"

"Nothing! It is sure, and there is no sport in it, therefore."

The music came to an end; Barbara stood free, smiling and dangerous. "I thank you, Etienne! If you knew the cross humour I was in! Now! Oh, it is entirely finished!" She turned upon her heel; her gaze swept the room, and found Colonel Audley. She crossed the floor towards him, her draperies hushing about her feet as she walked.

"That's a grand creature!" suddenly remarked Wellington, his attention caught. "Who is she, Duchess?"

The Duchess of Richmond glanced over her shoulder. "Barbara Childe," she answered. "She is a granddaughter of the Duke of Avon."

"Barbara Childe, is she? So that's the prize that lucky young dog of mine has won! I must be off to offer my congratulations!" He left her side as he spoke, and made his wayy to where Colonel Audley and Barbara were standing.

His congratulations, delivered with blunt heartiness, were perfectly well received by the lady. She shook hands, and met that piercing eagle stare with a look of candour, and her most enchanting smile. The Duke stayed talking to her until the quadrille was forming, but as soon as he saw the couples taking up their positions, he said briskly: "You must take your places, or you will be too late. No need to ask whether you dance the quadrille, Lady Barbara! As for this fellow, Audley, I'll engage for it he won't disgrace you."

He waved them on to the floor, called a chaffing word to young Lennox on the subject of his celebrated pas de zephyr, and stood back to watch the dance for a few minutes. Lady Worth, only a few paces distant, thought it must surely be impossible for anyone to look more carefree than his lordship. He was smiling, nodding to acquaintances, evidently enjoying himself. She watched him, wondering at him a little, and presently, as though aware of her gaze, he turned his head, recognised her, and said: "Oh, how d'ye do? A pretty sight, isn't it?"

She agreed to it. "Yes, indeed. Do all your staff officers perform so creditably, Duke? They put the rest quite in the shade."

"Yes, I often wonder where would Society be without my boys?" he replied. "Your brother acquits himself very well, but I believe that young scamp, Lennox, is the best of them. There he goes - but his partner is too heavy on her feet! Audley has the advantage of him in that respect."

"Yes," she acknowledged. "Lady Barbara dances very well."

"Audley's a fortunate fellow," said the Duke decidedly. "Won't thank me for taking him away from Brussels, I daresay. Don't blame him! But it can't be helped."

"You are leaving us, then?"

"Oh yes - yes! for a few days. No secret about it: I have to visit the Army."

"Of course. We shall await your return with impatience, I assure you, praying the Ogre may not descend upon us while you are absent!"

He gave one of his sudden whoops of laughter. "No fear of that! It's all nonsense, this talk about Bonaparte! Ogre! Pooh! Jonathan Wild, that's my name for him!" He saw her look of astonishment, and laughed again, apparently much amused, either by her surprise or by his own words.

She was conscious of disappointment. He had been described to her as unaffected: he seemed to her almost inane.

Chapter Eight

Upon the following day was published a General Order, directing officers in future to make their reports to the Duke of Wellington. Upon the same day, a noble-browed gentleman with a suave address and treat tact, was sent from Brussels to the Prussian Headquarters, there to assume the somewhat arduous duties of military commissioner to the Prussian Army. Sir Henry Hardinge had lately been employed by the Duke in watching Napoleon's movements in France. He accepted his new role with his usual equanimity, and commiserated with by his friends on the particularly trying nature of his commission, merely smiled, and said that General von Gneisenau was not likely to be as tiresome as he was painted.

The Moniteur of this 11th day of April published loomy tidings. In the south of France, the Duc D'Angouleme's enterprise had failed. Angouleme had led his mixed force on Lyons, but the arrival from Paris of a competent person of the name of Grouchy had ennded Royalist hopes in the south. Angouleme and his masterful wife had both set sail from France, and his army was fast dwindling away.

It was not known what King Louis, in Ghent, made of these tidings, but those who were acquainted with his character doubted whether his nephew's failure would much perturb him. Never was there so lethargic a monarch: one could hardly blame France for welcoming Napoleon back.

The news disturbed others, however. It seemed as though it were all going to start again: victory upon victory for Napoleon; France overrunning Europe. Shocking to think of the Emperor's progress through France, of the men who flocked to join his little force, of the crowds who welcomed him, hysterical with joy! Shocking to think of Marshal Ney, with his oath to King Louis on his conscience, deserting with his whole force to the Emperor's side! There must be some wizardry in the man, for in all France there had not been found sufficient loyal men to stand by the King and make it possible for him to hold his capital in Napoleon's teeth. He had fled, with his little Court, and his few troops, and if ever he found himself on his throne again it would be once more because foreign soldiers had placed him there.

But how unlikely it seemed that he would find himself there! With Napoleon at large, summoning his Champ de Mai assemblies, issuing his dramatic proclamations, gathering together his colossal armies, only the very optimistic could feel that there was any hope for King Louis.

Even Wellington doubted the ability of the Allies to put King Louis back on the throne, but this doubt sprang more from a just appreciation of the King's character than from any fear of Napoleon. Sceptical people might ascribe the Duke's attitude to the fact of his never having met Napoleon in the field, but the fact remained that his lordship was one of the few generals in Europe who did not prepare to meet Napoleon in a mood of spiritual defeat.

He accorded the news of Angouleme's failure a sardonic laugh, and laid the Moniteur aside. He was too busy to waste time over that.

He kept his staff busy too, a circumstance which displeased Barbara Childe. To be loved by a man who sent her brief notes announcing his inability to accompany her on expeditions of her planning was a new experience. When she saw him at the end of a :firing day, she rallied him on his choice of profession. "For the future I shall be betrothed only to civilians."

He laughed. He had been all the way to Oudenarde and back, with a message for General Colville, commanding the 4th Division, but he had found time to buy a ring of emeralds and diamonds for Barbara, end although there was a suggestion of weariness about his eyelids, he seemed to desire nothing as much as to dance with her the night through.

Waltzing with him, she said abruptly: "Are you tired?"

"Tired! Do I dance as though I were tired?"

"No, but you've been in the saddle nearly all day."

"Oh, that's nothing! In Spain I have been used to ride fifteen or twenty miles to a ball, and be at work again by ten o'clock the next day."

"Wellington trains admirable suitors," she remarked. "How fortunate it is that you dance so well, Charles!"

"I know. You would not otherwise have accepted me."

"Yes, I think perhaps I should. But I should not dance with you so much. I wish you need not leave Brussels just now."

"So do I. What will you do while I am away? Flirt with your Belgian admirer?"

She looked up at him. "Don't go!" He smiled, but shook his head.

"Apply to the Duke for leave, Charles!"

He looked started. As his imagination played with the scene her words evoked, his eyes began to dance.

"Unthinkable!"

"Why? You might well ask the Duke!"

"Believe me, I might not!"

She jerked up a shoulder. "Perhaps you don't wish for leave?"

"I don't," he said frankly. "Why, what a fellow I should be if I did!"

"Don't I come first with you?"

He glanced down at her. "You don't understand, Bab."

"Oh, you mean to talk to me of your duty!" she said impatiently. "Tedious stuff!"

"Very. Tell me what you will do while I am away."

"Flirt with Etienne. You have already said so. Have I your permission?"

"If you need it. It's very lucky: I leave Brussels on the 16th, and Lavisse will surely arrive on the 15th for the dinner in honour of the Prince of Orange. I daresay he'll remain a day or two, and so be at your disposal."

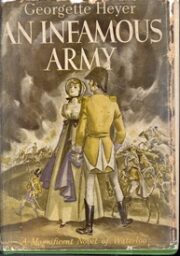

"An Infamous Army" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "An Infamous Army". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "An Infamous Army" друзьям в соцсетях.