"Not jealous, Charles?"

"How should I be? You wear my ring, not his."

His guess was correct. The Comte de Lavisse appeared in Brussels four days later to attend the Belgian dinner at the Hotel d'Angleterre. He lost no time in calling in the Rue Ducale, and on learning that Lady Barbara was out, betook himself to the Park, and very soon came upon her ladyship, in company with Colonel Audley, Lady Worth and her offspring, Sir Peregrine Taverner, and Miss Devenish.

The party seemed to be a merry one, Judith being in spirits and Barbara in a melting mood. It was she who held Lord Temperley's leading strings, and directed his attention to a bed of flowers. "Pretty lady!" Lord Temperley called her, with weighty approval.

"Famous!" she said. She glanced up at Judith, and said with a touch of archness: "I count your son one of my admirers, you see!"

"You are so kind to him I am sure it is no wonder," Judith responded, liking her in this humour.

"Thank you! Charles, set him on your shoulder, and let us take him to see the swans on the water. Lady worth, you permit?"

"Yes indeed, but I don't wish you to be teased by him!"

"No such thing!" She swooped upon the child, and lifted him up in her arms. "There! I declare I could carry you myself!"

"He's too heavy for you!"

"He will crush your pelisse!"

She shrugged as these objections were uttered, and relinquished the child. Colonel Audley tossed him up on to his shoulder, and the whole party was about to walk in the direction of the pavilion when Lavisse, who had been watching from a little distance, came forward, and clicked his heels together in one of his flourishing salutes.

Lady Worth bowed with distant civility; Barbara looked as though she did not care to be discovered in such a situation; only the Colonel said with easy good humour: "Hallo! You know my sister, I believe. And Miss Devenish - Sir Peregrine Taverner?"

"Ah, I have not previously had the honour! Mademoiselle! Monsieur!" Two bows were executed; the Count looked slyly towards Barbara, and waved a hand to include the whole group. "You must permit me to compliment you upon the pretty tableau you make; I am perhaps de trop, but shall beg leave to join the party."

"By all means," said the Colonel. "We are taking my nephew to see the swans."

"You cannot want to carry him, Charles," said Judith in a low voice.

"Fiddle!" he replied. "Why should I not want to carry him?"

She thought that the picture he made with the child on his shoulder was too domestic to be romantic, but could scarcely say so. He set off towards the pavilion with Miss Devenish beside him; Barbara imperiously demanded Sir Peregrine's arm; and as the path was not broad enough to allow of four persons walking abreast, Judith was left to bring up the rear with Lavisse.

This arrangement was accepted by the Count with all the outward complaisance of good manners. Though his eyes might follow Barbara, his tongue uttered every civil inanity required of him. He was ready to discuss the political situation, the weather, or mutual acquaintances, and, in fact, touched upon all these topics with the easy address of a fashionable man.

Upon their arrival at the sheet of water by the pavilion his air of fashion left him. Judith was convinced that nothing could have been further from nis inclination than to throw bread to a pair of swans, gut he clapped his hands together, declaring that the swans must and should be fed, and ran off to the pavilion to procure crumbs for the purpose.

He came back presently with some cakes, a circumstance which shocked Miss Devenish into exclaiming against such extravagance.

"Oh, such delicious little cakes, and all for the swans! The stale bread would have been better!"

The Count said gaily: "They have no stale bread, Mademoiselle; they were offended at the very question. So what would you?"

"I am sure the swans will much prefer your cakes Etienne," said Barbara, smiling at him for the first time. "If only you may not corrupt their tastes!" remarked Audley, holding on to his nephew's skirts.

"Ah, true! A swan with an unalterable penchant for cake . I fear he would inevitably starve!"

"He might certainly despair of finding another patron with your lavish notions of largess," observed Barbara.

She stepped away from the group, in the endeavour to coax one of the swans to feed from her hand; after a few moments the Count joined her, while Colonel Audley still knelt, holding his nephew on the brink of the lake, and directing his erratic aim in crumb throwing.

Judith made haste to relieve him of his charge, saying in an undervoice as she bent over her son: "Pray, let me take Julian. You do not want to be engaged with him."

"Don't disturb yourself, my dear sister. Julian and I are doing very well, I assure you."

She replied with some tartness: "I hope you will not be stupid enough to allow that man to take your place beside Barbara! There, get up! I have Julian fast."

He rose, but said with a smile: "Do you think me a great fool? Now I was preening myself on being a wise man!"

He moved away before she could answer him, and joined Miss Devenish, who was sitting on a rustic bench, drawing diagrams in the gravel with the ferrule of her sunshade. In repose her face had a wistful look, but at the Colonel's approach she raised her eyes, and smiled, making room for him to sit beside her.

"Of all the questions in the world I believe.What are you thinking about? to be the most impertinent," he said lightly.

She laughed, but with a touch of constraint. "Oh - I don't know what I was thinking about! The swans - the dear little boy - Lady Worth - how I envy her!"

These last words were uttered almost involuntarily. The Colonel said: "Envy her? Why should you do so?"

She coloured, and looked down. "I don't know how I came to say that. Pray do not regard it!" She added in a stumbling way: "One does take such fancies! It is only that she is so happy, and good…"

"Are you not happy?" he asked. "I am sure you are food."

She gave her head a quick shake. "Oh no! At least, I mean, of course I am happy. Please do not heed me! I am in a nonsensical mood today. How beautiful Lady Barbara looks in her bronze bonnet and pelisse." She glanced shyly at him. "You must be very proud. I hope you will be very happy too."

"Thank you. I wonder how long it will be before I shall be wishing you happy in the same style?" he said, with a quizzical smile.

She looked started. A blush suffused her cheeks, and her eyes brightened all at once with a spring of tears. "Oh no! Impossible! Please do not speak of it!"

He said in a tone of concern: "My dear Miss Devenish, forgive me! I had no notion of distressing you, upon my honour!"

"You must think me very foolish!"

"Well," he said, in a rallying tone, "do you know, I do think you a little foolish to speak of your marriage as impossible! Now you will write me down a very saucy fellow!"

"Oh no! But you don't understand! Here is Lady Barbara coming towards you: please forget this folly!"

She got up, still in some agitation of spirit, and walked quickly away to Judith's side.

"Good God! did my approach frighten the heiress away?" asked Barbara, in a tone of lively amusement. "Or was it your gallantry, Charles? Confess! You have been trifling with her!"

"What, in such a public place as this?" protested the Colonel. "You wrong me, Bab!"

She said with a gleam of fun: "I thought you liked public places, indeed I did! Parks - or Allees!"

"Allees!" ejaculated Lavisse. "Do not mention that word, I beg! I shall not easily forgive Colonel Audley for discovering, with the guile of all staff officers (an accursed race!), that you ride there every morning."

The Colonel laughed. Barbara took his arm saying: "I have made such a delightful plan, Charles. I am quite tired of the Allee Verte. I am going further afield, with Etienne."

"Are you?" said the Colonel. "A picnic? I don't advise it in this changeable weather, but you won't care for that. Where do you go?"

It was Lavisse who answered. "Do you know the Chateau de Hougoumont, Colonel? Ah, no! How should you, in effect? It is a little country seat which belongs to a relative of mine, a M. de Luneville."

"I know the Chateau," interrupted the Colonel. "It is near the village of Merbe Braine, is it not, on the Nivelles road?"

The Count's brows rose. "You are exact! One would say you knew it well."

"I had occasion to travel over that country last year," the Colonel responded briefly. "Do you mean to make your expedition there? It must be quite twelve or thirteen miles away."

"What of that?" said Barbara. "You don't know me if you think I am so soon tired. We shall ride through the Forest, and take luncheon at the Chateau. It will be capital sport!"

"Of whom is this party to consist?" he enquired. "Of Etienne and myself, to be sure."

He returned no answer, but she saw a grave look in his face, which provoked her into saying: "I assure you Etienne is very well able to take care of me."

"I don't doubt it," he replied.

Lady Worth had joined them by this time, and was listening to the interchange in silence, but with a puckered brow. The whole party began to walk away from the lake, and Judith, resigning her son into Peregrine's charge, caught up with Barbara, and said in a low voice: "Forgive me, but you are not in earnest?"

"Very seldom, I believe."

"This expedition with the Count: you cannot have considered what a singular appearance it will give you!"

"On the contrary: I delight in singularity."

Judith felt her temper rising; she managed to control it, and to say in a quiet tone: "You will think me impertinent, I daresay, but I do most earnestly counsel you to give up the scheme. I can have no expectation of my words weighing with you, but I cannot suppose you to be equally indifferent to my brother's wishes. He must dislike this scheme excessively."

"Indeed! Are you his envoy, Lady Worth?"

Judith was obliged to deny it. She was spared having to listen to the mocking rejoinder, which, she was sure, hovered on the tip of Barbara's tongue, by Colonel Audley's coming up to them at that moment. He stepped between them, offering each an arm, and having glanced at both their faces, said: "I conclude that I have interrupted a duel. My guess is that Judith has been preaching propriety, and Bab announcing herself a confirmed rake."

"I have certainly been preaching propriety," replied Judith. "It sounds odious, and I fear Lady Barbara has found it so."

"No! Confoundedly boring!" said Barbara. "I am informed, Charles, that you will dislike my picnic scheme excessively. Shall you?"

"Good God no! Go, by all means, if you wish to and can stand the gossip."

"I am quite accustomed to it," she said indifferently.

Judith felt so much indignation at the lack of feeling shown by this remark that she drew her hand away from the Colonel's arm, and dropped behind to walk with her brother. This left Miss Devenish to the Count's escort, an arrangement which continued until Barbara left the party. The Count then requested the honour of being allowed to conduct her home; Colonel Audley, who was obliged to call at Headquarters, made no objection, and Miss Devenish found herself once more in the company of Sir Peregrine, Lady Worth and Colonel Audley walking ahead of them.

After a few moments, Judith said in a vexed tone: "You will surely not permit her to behave with such impropriety!"

"I see no impropriety," he replied.

"To be alone with that man the whole day!"

"An indiscretion, certainly."

She walked on beside him in silence for some way, but presently said: "Why do you permit it?"

"I have no power to stop her even if I would."

"Even if you would? What can you mean?"

"She must be the only judge of her own actions. I won't become a mentor."

"Charles, how nonsensical! Do you mean to let yourself be ridden over roughshod?"

" Neither to be ridden over nor to ride roughshod," he answered. "To manage my own affairs in my own way, however."

" I beg your pardon," she said, in a mortified voice.

He pressed her hand, but after a slight pause began to talk of something else. She attempted no further discussion with him on the subject of the picnic, but to Worth, later, spoke her mind with great freedom. He listened calmly to all she had to say, but when she demanded to know his opinion, replied that he thought the intervention to have been ill-judged.

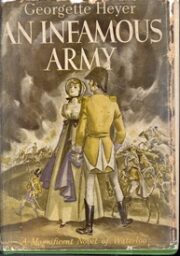

"An Infamous Army" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "An Infamous Army". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "An Infamous Army" друзьям в соцсетях.