He led Barbara into the set that was forming. A hand clapped Colonel Audley on the shoulder. "Hallo, Charles! Slighted, my boy?"

The Colonel turned to confront Lord Robert Manners. "You, is it? How are you, Bob?"

"Oh, toll-loll!" said Manners, giving his pelisse a hitch. "I have just been telling Worth all the latest London scandal. You know, you're a paltry fellow to be enjoying yourself on the staff in stirring times like these, upon my word you are! I wish you were back with us."

"Enjoying myselfl You'd better try being one of the Beau's ADCs, my boy! You don't know when you're well off, all snug and comfortable with the Regiment!"

"Pho! A precious lot of comfort we shall have when we go into action. When you trot off in your smart cocked hat, with a message in your pocket, think of us, barging to death or glory!"

"I will," promised the Colonel. "And when you're enjoying your nice, packed charge, spare a thought for the lonely and damnably distinctive figure galloping hell for leather with his message, wishing to God every french sharpshooter didn't know by his cocked hat he was a staff officer, and wondering whether his horse is going to hold up under him or come down within easy reach of the French lines: he will very likely be me!"

"Oh, well!" said Lord Robert, abandoning the argument. "Come and have a drink, anyway. I have a good story to tell you about Brummell!"

The story was told, others followed it; but presently Lord Robert turned to more serious matters, and said, over a glass of champagne: "But that's enough of London! Between friends, Charles, what's happening here?"

"It's pretty difficult to say. We get intelligence from Paris, of course, and what we don't hear Clarke does: but one's never too sure of one's sources. By what we can discover, the French aren't by any means unanimous over Boney's return. All this enthusiasm you hear of belongs to the Army. It wouldn't surprise me if Boney finds himself with internal troubles brewing. Angouleme failed, of course; but we've heard rumours of something afoot in La Vendee. One thing seems certain: Boney's in no case yet to march on us. We hear of him leaving Paris, and of his troops marching to this frontier - they are marching, but he's not with them."

"What about ourselves? How do we go on?"

"Well, we can put 70,000 men into the field now, which is something."

"Too many 2nd Battalions," said Lord Robert. "Under strength, aren't they?"

"Some of them. You know how it is. We're hoping to get some of the troops back from America. But God knows whether they'll arrive in time! We miss Murray badly - but we hear we're to have De Lancey in his place, which will answer pretty well. By the by, he's married now, isn't he?"

"Yes: charming girl, I believe. What are the Dutch and Belgian troops like? We don't hear very comfortable reports of them. Disaffected, are they?"

"They're thought to be. It wouldn't be surprising: half of them have fought under the Eagles. I suppose the Duke will try to mix them with our own people as much as possible, as he did with the Portuguese. Then there will be the Brunswick Oels Jagers: they ought to do well, though they aren't what they were when we first had them with us."

"Well, no more is the Legion," said Lord Robert.

"No: they began to recruit too many foreigners. But they're good troops, for all that, and they've good generals. I don't know what the other Hanoverians are like: there's a large contingent of them, but mostly Landwehr battalions."

"It sounds to me," said Lord Robert, draining his glass, "like a devilish mixed bag. What are the Prussians like?"

"We don't see much of them. Hardinge's with them: says they're a queer set, according to our notions. When Blucher has a plan of campaign, he holds conferences with all his generals, and they discuss it, and argue over it under his very nose. I should like to see old Hookey inviting Hill, and Alten, and Picton, and the rest, to discuss his plans with him!"

Lord Robert laughed; Mr Creevey peeped into the room, and seeing the two officers, came in, rubbing his hands together, and smiling like one who was sure of his welcome. There might be news to be gleaned from Audley, not the news that was being bandied from lip to lip, but titbits of private information, such as an oficer on the Duke's staff would be bound to hear. He had buttonholed the Duke a little earlier in the evening, but had not been able to get anything out of him but nonsense. He talked the same stuff as ever, laughing a great deal, pooh-poohing the gravity of the political situation, giving it as his opinion that Boney's return would come to nothing. Carnot and Lucien Bonaparte would get up a Republic in Paris; there would never be any fighting with the Allies; the Republicans would bea: Bonaparte in a very few months. He was in a joking mood, and Mr Creevey had met jest with jest, but thought his lordship cut a sorry figure. He allowed him to be very natural and good humoured, but could no perceive the least indication of him of superior talents. He was not reserved; quite the reverse: he was communicative; but his conversation was not that of a sensible man.

"Well? What's the news?" asked Mr Creevey cheerily. "How d'ye do, Lord Robert?"

"Oh, come, sir! It's you who always have the latest news," said Colonel Audley. "Will you drink a glass of champagne with us?"

"Oho, so that's what you are up to! You're a most complete hand, Colonel! Well, just one then. What's the latest intelligence from France, eh?"

"Why, that Boney's summoning everyone to are assembly, or some such thing, in the Champ du Mars."

"I know that," said Mr Creevey. "I have been talking about it to the Duke. We have had quite a chat together. I can tell you, and some capital jokes too. He believes it won't answer, this Champ de Mai affair; that there will be an explosion; and the whole house of cards will come tumbling about Boney's ears."

"Ah, I daresay," responded the Colonel vaguely. "Don't know much about these matters, myself."

Mr Creevey drank up his wine, and went away in search of better company. He found it presently in the group about Barbara Childe. She had gathered a numbered of distinguished persons about her, just the sort of people Mr Creevey liked to be with. He joined the group, noticing with satisfaction that it included General Don Miguel de Alava, a short, sallow-faced Spaniard, with a rather simian cast of countenance, quick-glancing eyes, and a tongue for ever on the wag. Alava had lately become the Spanish Ambassador at The Hague, but was at present acting as military commissioner to the Allied Army. He had been commissar at Wellington's Headquarters in Spain, and was known to be on intimate terms with the Duke. Mr Creevey edged nearer to him, his ears on the prick.

"But your wife, Alava! Is she not with you?" Sir William Ponsonby was demanding.

Up went the expressive hands; a droll look came into Alava's face. "Ah non, par exemple!" he exclaimed. "She stays in Spain. Excellente femme! - mais forte ennuyeuse!"

Caroline Lamb's voice broke through the shout of laughter. "General Alava, what's the news? You know it all! Now tell us! Do tell us!"

"Mais, madame, je n'en sais rien! Rien, rien, rien!" Decidedly, Mr Creevey was out of luck tonight.

Chapter Twelve

May came in, bringing trouble. There seemed to be no end to the difficulties for ever springing up round his lordship. Now it was Major-General Hinuber, querulously demanding leave to resign his staff, and to retire to some German spa, because he was not to command the Legion as a separate division: he might go with the Duke's goodwill, but it meant more letter writing, more trouble; now it was news from his brother William, in London: the Peace party was attacking his lordship in Parliament, accusing him of being little better than a murderer, because he had set his name to the declaration that made Napoleon hors la loi: he did not really care, he had never cared for public opinion, but it annoyed him. To attack a public servant absent on public service seemed to him "extraordinary and unprecedented". Then there was the constant fret of being obliged to deal with the Dutch King, a jealous man, continually raising difficulties, or turning obstinate over petty issues. He could be managed, in the end he would generally give way, but it took time to handle him, and time was what his lordship could least spare.

The question of the Hanoverian subsidy had become acute; King William should have shared the payment with Great Britain, but he was wriggling out of that obligation, on the score that he had only been bound to pay it while he had no troops of his own. His lordship had had an interview with the M. de Nagel over the business, but in the end he supposed the whole charge of the Hanoverian subsidy would fall upon Great Britain.

Trouble sprang up in the Prussian camp. The Saxon troops at Liege mutinied over some question of an oath of allegiance to the King of Prussia, and poor old Blucher was obliged to quit the town. The Saxons would have been willing enough to have come over to the British camp, but his lordship did not want such fellows, and knew that the Prussians would never agree to his having them if he did. They would have to be got rid of before they spread disaffection through the Army, but the question was how to get them out of the country. Blucher wanted them to be embarked on British ships, but his lordship had no transports; his troops were sent out to him on hired vessels, which returned to England as soon as their cargoes were landed. If they were to be escorted through the Netherlands, King William's permission must be obtained, but there was no inducing Blucher to realise the propriety of referring to the King. It would fall on his lordship's shoulders to arrange matters, writing to Hardinge, to Blucher, to King William.

And, like a running accompaniment to the rest, the bickering correspondence with Torrens over staff appointments dragged on, until his lordship dashed off one of his hasty, biting notes, requesting that it should cease. "The Commander-in-Chief has a right to appoint whom he chooses, and those whom he appoints shall be employed," he wrote in a stiff rage. "It cannot be expected that I should declare myself satisfied with these appointments till I shall find the persons as fit for their situations as those whom I should have recommended to his Royal Highness."

On May 6th his lordship was able to tell Lord Bathurst that King William had placed the Dutch-Belgian Army under his command. The appointment had been delayed on various unconvincing pretexts, but at last. and when his lordship had reached the end of his patience, it had been made. Things should go better now; he could begin to pull the whole Allied Army into shape, drafting the troops where he thought proper without the hindrance of having to make formal application for permission to His Majesty.

The month wore on; the weather grew warmer; no more friendly logfires in the grates, no more fur-lined pelisses for the ladies. Out came the cambrics and the muslins: lilac, pomona green, and pale puce, made into wispy round dresses figured with rosebuds, with row upon row of frills round the ankles. Knots of jaunty ribbons adorned low corsages, and gauze scarves floated from plump shoulders in a light breeze. The feathered velvet bonnets and the sealskin caps were put up in camphor. Hats were the rage; chip hats, hats of satin straw, of silk, of leghorn, and of willow: high-crowned, flat-crowned, with full-poke fronts, and with curtailed poke fronts: hats trimmed with clusters of flowers, or bunches of bobbing cherries, with puffs of satin ribbons, drapings of thread net, and frills of lace. Winter half boots of orange Jean or sober black kid were discarded: the ladies tripped over cobbled streets in sandals and slippers. Red morocco twinkled under rushed skirts; Villager hats and Angouleme bonnets framed faces old or young, pretty or plain; silk openwork mittens covered rounded arms; frivolous little parasols on long beribboned handles shaded delicate complexions from the sun's glare. Denmark Lotion was in constant demand, and Distilled Water of Pineapples; strawberries were wanted for sunburnt cheeks; Chervil Water, for bathing a freckled skin.

The balls, the concerts, the theatres continued, but picnics were added to the gaieties now, charming expeditions, with flowering muslins squired by hot scarlet uniforms; the ladies in open carriages; the gentlemen riding gallantly beside; hampers of cold chicken and champagne on the boxes; everyone lighthearted; flirtation the order of the day. There were reviews to watch, fetes to attend; day after day slid by in a pursuit of pleasure; days that were not quite real, that belonged to some half-realised dream. Somewhere in the south was a Corsican ogre, who might at any moment break into the dream and shatter it, but distance shrouded him; and, meanwhile, into the Netherlands was streaming an endless procession of British troops, changing the whole face of the country, swarming in every village; lounging outside estaminets, in forage caps, with their jackets unbuttoned; trotting down the rough, dusty roads with plumes flying and accoutrements jingling; haggling with shrewd Flemis farmers in their broken French; making love to giggling girls in starched white caps and huge voluminous skirts: spreading their Flanders tents over the meadows: striding through the streets with clanking spurs and swinging sabretaches. Here might be seen a looped and tasselled infantry shako, narrow-topped and leathernpeaked; there the bell-topped shako of a Light Dragoon, with its short plume and ornamental cord; o: the fur cap of a hussar; or the glitter of sunlight on a Heavy Dragoon's brass helmet, with its jutting crest and waving plume.

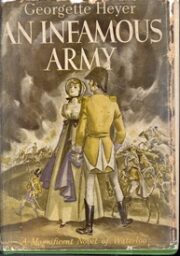

"An Infamous Army" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "An Infamous Army". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "An Infamous Army" друзьям в соцсетях.