They were soon roused from this condition by the necessity of calming the servants, some of whom were hysterical with fright. Barbara went out into the hall among them, and very soon restored order. While Judith occupied herself with reassuring those whose alarm had had the effect of bereaving them of all power of speech or of action, she dealt in a more drastic manner with the rest, swearing at the butler, and emptying jugs of water over any fille de chambre unwise enough to fall into a fit of hysterics.

By the time Worth returned, the household was quiet, and Barbara had gone back into the salon with Judith, who had temporarily forgotten her own fears in amusement at her guest's ruthless methods.

Worth brought reassuring tidings. The noise they had heard had been caused by a long train of artillery, passing through the town on its way to the battlefield.

The panic had arisen from a false notion having got about that the train was in retreat. People had rushed out of their houses in every stage of undress; a rumour that the French were coming had spread like wildfire; and the greatest confusion reigned until it became evident, even to the most foolish in the crowd, that the artillery was moving, not away from the field of action but towards it.

"Is that all?" exclaimed Barbara. "Well, if there is no immediate need for us to become heroines we may as well go to bed. I, at any rate, shall do so."

"Oh," said Judith, with a little show of playfulness, "you need not think that I shall be behind you in sangfroid: you have put me quite on my mettle!"

Goodnights were exchanged; both ladies retired again to their rooms, each with a much better opinion of the other than she had had at the beginning of what, in retrospect, seemed to have been the longest day of her life.

Chapter Nineteen

The night was disturbed. Many of the Bruxellois seemed to be afraid to go to bed, and spent the hours sitting in their houses with ears on the prick, ready to run out into the streets at the smallest alarm. Just before dawn a melancholy cortege entered the town, bearing the Duke of Brunswick's body. Numbers of spectators saw it pass through the streets. The sable uniforms of the Black Brunswickers, the grim skull-and-crossbones device upon their caps and the grief in their faces, awed the thin crowds into silence. A feeling of dismay was created; when the sad procession had passed, people dispersed slowly, some to wander about in an aimless fashion till daylight, others returning to their houses to lie down fully clothed upon their beds or to drop uneasily asleep in chairs.

Between five and six in the morning, after an interval of quiet, commotion broke out again. A troop of Belgian cavalry, entering by the Namur Gate, galloped through the town in the wildest disorder, overturning market-carts, thundering over the cobbles, their smart green uniforms white with dust and their horses roaming. They had all the appearance of men hotly pursued, and scarcely drew rein in their race through the town to the Ninove Gate. All was panic; they were shouting: "Les Franqais sont ici!" and the words were immediately taken up by the terrified crowds who saw them pass. The French were said to be only a few miles outside the town, the Allied Army in full retreat before them. Distracted Belgians ran to collect their more precious belongings, and then wandered about carrying the oddest collection of goods, not knowing where to go, or what to do. Women became hysterical , filles de chambre rushing into hotel bedrooms to rouse sleepy visitors with the news that the French were at the gates; mothers clasping their children in their arms and screaming at their husbands to transport them instantly to safety. The drivers of the carts and the wagons drawn up in the Place Royale caught the infection; no sooner had the cavalry flashed through the great square than they set off down every street, rocking and lurching over the pave in their gallop for the Ninove Gate. In a few minutes the Place was deserted except for the people who still drifted about, spreading the dreadful news, or begging complete strangers for the hire of a pair of horses; and for a few market-carts driven into the town by stolid peasants in sabots and red night-caps, who seemed scarcely to understand what all the pandemonium was about.

Many of the English visitors behaved little better. Some of those who, on the night of the 15th, had stoutly declared their intention of remaining Brussels, now ordered their carriages, or, if they possessed none, hurried about the town trying to engage horses to procure passages on the canal track-boats. For the most part, however, the flight of a troop of Belgic cavalry did not rouse much feeling of alarm in British breasts. Ladies busied themselves, as they had done the previous day, with preparations for the wounded, and if there were some who thought the cessation of all gun-fire ominous, there were others who considered it to be a sure sign that all must be well.

Judith and Barbara again went to the Comtesse de Ribaucourt's. On entering the house Judith encountered Georgiana Lennox, who came up to her with a white face and trembling lips, trying to speak calmly on some matter of a consignment of blankets. She was scarcely able to control her voice, and broke off to say: "Forgive me, this is foolish! Only it is so dreadful - I don't seem able to stop crying."

Judith took her hand, saying with a good deal of concern: "Oh, my poor child! Your brothers -?"

"Oh no, no!" Georgiana replied quickly. "But Hay has been killed!" She made an effort to control herself. "He was almost like one of my brothers. It is stupid - I know he would not care for that, but I can't get it out of my head how cross I was with him for being so glad to be going into action." She tried to smile. "I scolded him. I wouldn't dance with him any more, and then I never saw him again. He went away so excited, and now he's been killed, and I didn't even say goodbye to him."

Judith could only press her hand. Georgiana said rather tightly: "I can't believe he's dead, you know. He said: 'Georgy! We're going to war! Was there ever anything so splendid?' And I was cross."

"Dearest Georgy, you mustn't think of that. I am sure he did not."

"Oh no! I know I'm being silly. Only I wish I had not scolded him." She brushed her hand across her eyes. "He was General Maitland's aide-de-camp, you know. Now that he has been killed William feels that he must rejoin Maitland, and he is not fit to do so."

"Your brother! Oh, he cannot do so. His arm is still in a sling, and he looks so ill!"

"That is what Mama feels, but my father agrees that it is William's duty to go to General Maitland. I do not know what will come of it." Her lips quivered again; she said inconsequently: "Do you remember how beautifully the Highlanders danced at our ball? They are all dead."

"Oh, hush, my dear, don't think of such things! Not all!"

"Most of them. They were cut to pieces by the cuirassiers. They say the losses in the Highland brigade are terrible."

Judith could not speak. She had seen the Highlanders march out of Brussels in the first sunlight, striding to war to the music of their own fifes, and the memory of that proud march brought a lump into her throat. She pressed Georgiana's hand again, and released it, turning away to hide the sudden rush of tears to her own eyes.

She and Barbara returned home a little after noon, to find that Worth had just come back from visiting Sir Charles Stuart. He was able to tell them that an aide-de-camp had ridden in during the morning, having left the field at 4a.m. He reported that after a very sanguinary battle the Allied Army had remained in possession of the ground. Towards the close of the action the cavalry had come up, having been delayed by mistaken orders. It had not been engaged on the 16th, but would certainly be in the thick of it today, if the French attack were renewed, as the Duke was confident it would be.

The ladies had hardly taken off their hats when the sound of cheering reached the house; they ran out to the end of the street, where a crowd had collected, and were in time to see a number of French prisoners being marched under guard towards the barracks of Petit Chateau.

But the heartening effect of this sight was not of long duration. The next news that reached Brussels was that the Prussians had been defeated at Ligny, and were in full retreat. The intelligence brought a fresh feeling of dismay, which was made the more profound by the arrival, a little later, of the first wagon-loads of wounded. In a short time the streets were full of the most pitiable sights. Men who were able to walk had dragged themselves to Brussels on foot all through the night, some managing to reach the town, many collapsing on the way, and dying by the roadside from the effects of their wounds.

Except among those whom panic had rendered incapable of any rational action, the arrival of the wounded made people forget their own alarms in the more pressing need to do what they could to alleviate the sufferings of the soldiers. Ladies who had never encountered more unnerving sights than a pricked finger or the graze on a child's knee, went out into the streets with flasks of brandy and water, and the shreds of petticoats torn up to provide bandages; and stayed until they dropped from fatigue, stanching the blood that oozed from ghastly wounds; providing men who were dying on the pavements with water to bring relief to their last moments; rolling blankets to form pillows for heads that lolled on the cobbles; collecting straw to make beds for those who, unable to reach their own billets, had sunk down on the road; and accepting sad, last tokens from dying men who thought of wives, and mothers, and sweethearts at home, and handed to them a ring, a crumpled diary, or a laboriously scrawled letter.

Judith and Barbara were among the first to engage on this work. Neither had ever come into anything but the most remote contact with the results of war; Judith was turned sick by the sight of blood congealed over ugly contusions, of the scraps of gold lace embedded in gaping wounds, of dusty rags twisted round shattered joints, and of grey, pain-racked faces lying upturned upon the pavement at her feet. There was so little that could be accomplished by inexpert hands; the patient gratitude for a few sips of water of men whose injuries were beyond her power to alleviate brought the tears to her eyes. She brushed them away, spoke soothing words to a boy crumpled on the steps of a house, and sobbing dryly, with his head against the railings; bound fresh linen round a case-shot wound; spent all the Hungary Water she owned in reviving men who had covered the weary miles from Quatre-Bras only to fall exhausted in the gutters of Brussels.

Occasionally she caught sight of Barbara, her flowered muslin dusty round the hem with brushing the cobbles, and a red stain on her skirt where an injured head had lain in her lap. Once they met but neither spoke of the horrors around them. Barbara said briefly: "I'm going for more water. The chemists have opened their shops and will supply whatever is needed."

"For God's sake, take my purse and get more lint - as much of it as you can procure!" Judith said, on her knees beside a lanky Highlander, who was sitting against the wall with his head dropped on his shoulder.

"No need; they are charging nothing," Barbara replied. "I'll get it."

She passed on, making her way swiftly down the street. A figure in a scarlet coat lay across the pavement; she bent over it, saying gently: "Where are you hurt? Will you let me help you?" Then she saw that the man was dead, and straightened herself, feeling her knees shaking, and nausea rising in her throat. She choked it down, and walked on. A Highlander, limping along the road, with a bandage round his head and one arm pinned up by the sleeve across his breast, grinned weakly at her. She stopped, and offered him the little water that remained in her flask. He shook his head: "Na, na, I'm awa' to my billet. I shall do verra weel, ma'am."

"Are you badly hurt? Will you lean on my shoulder?"

"Och, I got a wee skelp wi' a bit of a shell, that's all. Gi'e your watter to the puir red-coat yonder: we are aye well respected in this toon! We ha' but to show our petticoat, as they ca' it, and the Belgians will ay gi'e us what we need!"

She smiled at the twinkle of humour in his eye, but said: "You've hurt your leg. Take my arm, and don't be afraid to lean on me."

He thanked her, and accepted the help. She asked him how the day had gone, and he replied, gasping a little from the pain of walking: "It's a bluidy business, and there's no saying what may be the end on't. Oor regiment was nigh clean swept off, and oor Colonel kilt as I cam' awa'. But I doot all's weel."

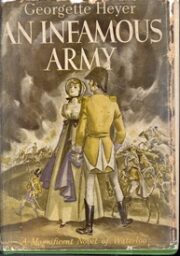

"An Infamous Army" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "An Infamous Army". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "An Infamous Army" друзьям в соцсетях.