"Lord Palmer told me he has heard stories of a ring of forgers rumored to work in London."

"Surely the keepers at the museum would notice the differences between the original and a forgery?"

"I don't think they would have any reason to question a piece after initially acquiring it."

"But how did Philip get the original? He must have believed he was buying a reproduction."

"That, Ivy, is precisely the point that is causing me much anxiety. Lord Palmer insists that Philip would never buy a reproduction. He was adamant in his belief."

"That's not so difficult. The piece came on the market, Philip determined it to be genuine, and bought it. Obviously he did not know it was supposed to be in the British Museum."

"But doesn't that seem odd? It's a striking piece, and, given the amount of time he spent in the Greco-Roman galleries, it seems unlikely that he had never seen it."

"Yes, I agree he most certainly had seen it. But think, Emily, how much there is in the British Museum. A person could never claim complete familiarity with even one collection. Philip probably thought his bust of Apollo similar to the one in the museum but not identical."

"To find two such busts attributable to Praxiteles himself is unthinkable. I've read everything I can about the artist, Ivy. Only one other of his original works has survived. Virtually everything that we know about him comes from Roman copies and ancient texts. An authentic Praxiteles is a treasure. Philip must have known that it belonged in the museum."

"You're not suggesting that he dealt knowingly with these forgers?"

"I hardly know what I'm suggesting." We sat silently for several moments. "I think we must consider the facts before us. I have the original Apollo that Praxiteles made. The one in the British Museum must be a very good forgery."

"Are you absolutely certain that yours is the original? Could the restorer be wrong?"

"I don't think so. He gives his reasoning in his note and says that he showed the piece to several others with whom he works. They unanimously agreed that it is authentic. Lord Palmer would not have recommended them if they were not competent, so I have no reason to doubt their conclusions."

"Is it even possible to copy something so well?"

"It certainly is. Did I ever tell you about a fascinating character Monsieur Pontiero introduced to me in Paris? A Mr. Attewater, whose career is copying antiquities. He was quite confident that his work is virtually indistinguishable from the originals."

"Does Mr. Attewater live in London?"

"He does."

"Perhaps he could go to the museum and look at their Apollo, then let us know if it is in fact a copy? If it is, we could alert the keeper."

"I'm not sure that I want to do that, Ivy."

"Why not?"

"We still do not know Philip's role in this. How did he come to have something that should be in the museum? Given what little we know, it appears that at best he purchased something of dubious provenance, and for a man of his character to have done such a thing would be inconceivable."

"Please forgive me for saying this, Emily. I know that you have grown very fond of Philip over the past few months, but what do we really know of him?"

"That is my concern, Ivy. I know from his diary that he did have strong feelings for me, and the portrait by Renoir confirms his romantic nature. But when it comes to matters of character, what firsthand information do we have?"

"Well..." Ivy looked around the room as she thought. "We may have no direct confirmation of excellent character, but I think you would have known if he were really bad, don't you? He treated you well during your marriage."

"He did, but I imagine that many a great criminal mind has the capacity to love a woman."

"Emily! Are you calling him a criminal?"

"No! I'm only saying that his treatment of me cannot be relied on to serve as an ultimate substantiation of his true nature. At any rate, we both know that I did not pay much attention to Philip while we were married. I learned almost nothing about him."

"What has made you believe now that he was a good man?"

"Primarily stories told to me by Lord Palmer and Colin Hargreaves. Andrew, too. However, Colin has been asking me some very strange questions about Philip's business transactions, specifically those concerning purchases of antiquities. I've just been through Philip's papers and found nothing that refers to them."

"Could Colin be collaborating with the forgers?"

"I'd sooner believe that of Colin than of Philip if it weren't for the physical evidence of Apollo. We haven't caught Colin with a stolen artifact."

"But Colin could still be involved. Why else would he be so interested in Philip's purchases? Did your husband have any other antiquities in the house?"

"Not to speak of. There is a vase in the library, but other than that, nothing," I said, shaking my head.

"A bit surprising for someone who was so interested in the subject, isn't it?"

"Apparently he kept his collection at Ashton Hall, where I shall have to visit as soon as possible. Perhaps I can find some documentation there. And I think I shall write to Cécile. Monsieur Fournier told me that Philip was looking for Apollo in Paris. Perhaps Cécile could determine if he did indeed purchase it there and from whom. There must be some simple explanation for the whole thing."

"I hope so, Emily. It would be rather shocking to have to completely reform your opinion of Philip after all the trouble you've gone to falling in love with him."

"You are rather understating things, my dear," I said. "Do you think Robert could spare you in order that you might accompany me to the country?"

"I'm certain he could be convinced." She giggled. "Men can so easily be persuaded."

Much to my surprise, it was Andrew, not Robert, who attempted to undermine our plans. He protested vehemently after receiving a note I sent canceling a trip to the theater.

"I cannot understand why you must rush off to the country, Emily. It makes no sense."

"Why does it have to make sense?" I asked. I felt that telling Andrew of my suspicions would be disloyal to Philip, and I had no intention of explaining my motives. "I haven't seen the house, Ivy will return to her own estate before long, and we have decided to have a bit of an adventure."

"Nonsense." He snorted. "I don't like the two of you traveling unaccompanied."

"We aren't. Miss Seward is coming with us."

"Margaret Seward is hardly the type of woman who is likely to put my mind at ease on any subject."

"Andrew, do not force me to become irritated with you," I said severely, wishing that I had not allowed Meg to lace me so tightly. I could hardly draw breath as I spoke. "Going to visit a house in which I, in a sense, live is hardly dangerous."

"How can you suggest that you live there when you have just admitted to never having seen it?"

"You know very well what I mean. I want to see the estate, and I want to go with my friends. Don't be difficult. We can go the theater when I return."

"I shall miss you," he said, reverting to his usual mode of charm.

"I shall be back in two days." I smiled.

"Before you go," he started. "My father is still waiting for those bloody papers of Philip's. May I come back tomorrow and look for them?"

"I don't see why not. I'll tell Davis to expect you."

5 JULY 1887

BERKELEY SQUARE, LONDON

Can hardly wait to depart for Greece, although things here better than expected.

After days spent agonizing over how best to present my suit, spoke to Lord Bromley at the Turf Club yesterday regarding his daughter. At the end of my rather elegant speech, the old man laughed heartily, got me a drink, and said that it was unlikely I could find a father in England who would not gladly relinquish his daughter to me. Delighted to offer me K's hand and assures me entire family would welcome our marriage. Went to Grosvenor Square today-overjoyed to report that my proposal has been accepted. Paris himself would envy me my bride...

16

"I don't think I truly appreciated how rich Philip really was until now," Ivy said as our carriage approached the entrance to Ashton Hall, Philip's family seat. "How long has it taken us to reach the house from the main road? I feel like I am at Windsor."

"You should never appraise a man's fortune from the outer appearance of his estate, Ivy. Reserve judgment until you have seen the entire inside. Lord Palmer has shut up two of the wings of his country house. Fortunes are not what they used to be."

"That is very true," Margaret agreed. "But these grounds are spectacular, Emily."

"You really ought to spend the holidays here," Ivy suggested.

"I shall have to give the matter serious consideration." I wondered what it would have been like to spend Christmas here with Philip. My family, of course, would have visited, as would his. Did he prefer Ashton Hall or London? I had no idea. I looked at Ivy and smiled, knowing how nervous she was at the prospect of hosting her own holiday celebrations for the first time. Robert's mother had already joined them and evidently had a great many ideas about the renovations the couple were making to her former home. Poor Ivy! Her sweet nature made it difficult for her to stand up to her mother-in-law, but I knew that as time passed, she would find her own mischievous, though harmless, ways of making sure she was the only mistress of her estate.

The carriage stopped in front of the magnificent house, and I looked in wonder for several moments before accepting the footman's assistance in descending to the drive. I wished that Cécile were with us, as the façade reminded me a bit of Versailles, albeit on a slightly smaller scale. Mrs. Henley, the housekeeper, greeted us at the door and began immediately apologizing for the state of the interior.

"I assure you I am not here to judge you, Mrs. Henley. I've only come to take a look at the place; I'm sorry I haven't done so before. I realize that you had very little warning of my arrival."

"His lordship sent so many boxes and asked that they not be disturbed. Emory stacked them in the library." The man standing at her side bowed slightly. "We didn't know what to do with them after we heard of Lord Ashton's death, madam, and didn't want to disturb you."

"Please do not worry yourself, Mrs. Henley. You've done quite well. What are these boxes, Emory?"

"I couldn't say, madam. They arrived quite regularly for several months before your wedding, so I assumed they were items you and his lordship had purchased to redecorate the house." I looked at my friends and raised an eyebrow before replying.

"Would you please take me to the library?"

"Of course, madam."

"Shall I bring you some tea, your ladyship?" Mrs. Henley inquired. "You must be in need of refreshment after your long trip. Those railroads are not as comfortable as they might be."

"That would be lovely, Mrs. Henley." I smiled. Margaret, Ivy, and I followed Emory through a seemingly endless maze of rooms until we reached the largest library I had ever seen in a house. The housekeeper told us it contained more than thirty thousand volumes, a number I would not have believed had I not been standing in their midst when I heard it. Margaret was immediately drawn to them and began investigating the contents of the shelves. Massive fireplaces stood at either end of the room, and the remaining wall space was lined with bookshelves that rose to the ceiling, whose gilded stucco was painted with scenes from Greek mythology. The furniture, although very masculine looking, was made from a light-colored wood, brightening the room. Sunlight poured through tall French doors that overlooked the gardens behind the house. Altogether it was a very pleasant library. The only fault, as Mrs. Henley had warned us, was an extremely large pile of shipping crates in the middle of the floor.

"What on earth do you think could be in them?" Ivy asked, trying to peer into one.

"Let's find out." I motioned for Emory to open the box nearest to me.

"Shall we try to guess what it is?" Ivy asked. "Hunting trophies?"

"I hope not!" I exclaimed.

"I beg your pardon, your ladyship, but those come in much larger crates," Emory said apologetically.

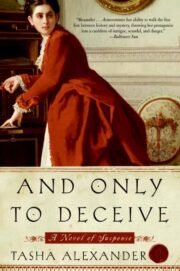

"And Only to Deceive" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "And Only to Deceive". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "And Only to Deceive" друзьям в соцсетях.