‘“I perceive,” said Mr. Beaumaris, “that we have much in common, ma’am. But I shall not allow a distaste for hired vehicles to be old-fashioned. Let us rather say that we have a little more nicety than the general run of our fellow-creatures!” He turned his head towards the butler. “Let a message be conveyed to the wheelwright, Brough, that he will oblige me by repairing Miss Tallant’s carriage with all possible expedition.”

Miss Tallant had nothing to do but thank him for his kind offices, and finish her Rhenish cream. That done, she rose from the table, saying that she had trespassed too long on her host’s hospitality, and must now take her leave of him, with renewed thanks for his kindness.

“The obligation, Miss Tallant, is all on my side,” he replied. “I am grateful for the chance which has made us acquainted, and shall hope to have the pleasure of calling upon you in town before many days.”

This promise threw Miss Blackburn into agitation. As she accompanied Arabella upstairs, she whispered: “My dear Miss Tallant, how could you? And now he means to call on you, and you have told him—oh dear, oh dear, what would your Mama say?”

“Pooh!” returned Arabella, brazening it out. “If he is indeed a rich man, he will not care a fig, or think of it again!”

“If he is—Good gracious, Miss Tallant, he must be one of the wealthiest men in the country! When I collected that he was in very truth Mr. Beaumaris I nearly swooned where I stood!”

“Well,” said the pot-valiant Arabella, “if he is so very grand and important you may depend upon it he has not the least intention of calling on me in town. And I am sure I hope he will not, for he is an odious person!”

She refused to be moved from this stand, or even to acknowledge that in Mr. Beaumaris’ person at least no fault could be found. She said that she did not think him handsome, and that she held dandies in abhorrence. Miss Blackburn, terrified that she might, in this alarming mood, betray her dislike of Mr. Beaumaris at parting, begged her not to forget what the barest civility rendered obligatory. She added that one slighting word uttered by him would be sufficient to wither any young lady’s career at the outset, and then wished that she had held her tongue, since this warning had the effect of bringing the militant sparkle back into Arabella’s eyes. But when Mr. Beaumaris handed her into the coach, and, with quite his most attractive smile, lightly kissed the tips of her fingers before letting her hand go, she bade him farewell in a shy little voice that gave no hint of her loathing of him.

The coach set off down the drive; Mr. Beaumaris turned, and in a leisurely way walked back into his house. He was pounced on in the hall by his injured friend, who demanded to know what the devil he meant by inflicting lemonade upon his guests.

“I don’t think Miss Tallant cared for my champagne,” he replied imperturbably.

“Well, if she didn’t, she could have refused it, couldn’t she?” protested Lord Fleetwood. “Besides, it was no such thing! She drank two glasses of it!”

“Never mind, Charles, there is still the port,” said Mr. Beaumaris.

“Yes, by God!” said his lordship, brightening. “And, mind, now! I expect the very best in your cellar! A couple of bottles of that ’75 of yours, or—”

“Bring it to the library, Brough—something off the wood!” said Mr. Beaumaris.

Lord Fleetwood, always the easiest of preys, rose to the bait without a moment’s hesitation. “Here, no, I say!” he cried, turning quite pale with horror. “Robert! No, really, Robert!”

Mr. Beaumaris lifted his brows in the blandest astonishment, but Brough, taking pity on his lordship, said in a soothing tone: “We have nothing like that in our cellars, I assure your lordship!”

Lord Fleetwood, perceiving that he had once more been gulled, said with strong feeling: “You deserve I should plant you a facer for that, Robert!”

“Well, if you think you can—!” said Mr. Beaumaris.

“I don’t,” replied his lordship frankly, accompanying him into the library. “But that lemonade was a dog’s trick to serve me, you know!” His brow puckered in an effort of thought. “Tallant! ... Did you ever hear the name before, for I’ll swear I never did?”

Mr. Beaumaris looked at him for a moment. Then his eyes fell to the snuff-box he had drawn from his pocket. He flicked open the box, and took a delicate pinch between finger and thumb. “You have never heard of the Tallant fortune?” he said. “My dear Charles—!”

V

Thanks to Mr. Beaumaris’s message, which worked so powerfully on the wheelwright as to cause him to ignore the prior claims of three other owners of damaged vehicles, Arabella was only kept waiting for one day in Grantham. Since the Quorn met there on the morning following her encounter with Mr. Beaumaris, she was able, from the window of a private parlour at the Angel and Royal Inn, to see just how he looked on horseback. She could have seen how Lord Fleetwood looked too, had she cared, but curiously enough she never even thought of his lordship. Mr. Beaumaris looked remarkably well, astride a beautiful thoroughbred, with long, sloping pasterns, and shoulders well laid back. She decided that Mr. Beaumaris’s seat was as good as any she had ever seen. The tops to his hunting-boots were certainly whiter than a mere provincial would have deemed possible.

The Hunt having moved off, there was nothing for two delayed travellers to do for the rest of the day but stroll about the town, eat their meals, and yawn over the only books to be found in the inn. But by the following morning the Squire’s carriage was brought round to the Angel, with a new pole affixed, and the horses well-rested, and the ladies were able to set forward betimes on the last half of their long journey.

Even Miss Blackburn was heartily sick of the road by the time the muddied carriage at last drew up outside Lady Bridlington’s house in Park Street. She was sufficiently well acquainted with the metropolis to feel no interest in the various sounds andsights which had made Arabella forget her boredom and her fidgets from the moment that the carriage reached Islington. These, to a young lady who had never seen a larger town than York in her life, were at once enthralling and bewildering. The traffic made her feel giddy, and the noise of post-bells, of wheels on the cobbled streets, and the shrill cries of itinerant vendors of coals, brick-dust, door-mats, and rat-traps quite deafened her. All passed before her wide gaze in a whirl; she wondered how anyone could live in such a place and still retain her sanity. But as the carriage, stopping once or twice for the coachman to enquire the way of nasal and not always polite Cockneys, wound its ponderous way into the more modish part of the town, the din abated till Arabella began even to entertain hopes of being able to sleep in London.

The house in Park Street seemed overpoweringly tall to one accustomed to a rambling two-storeyed country-house; and the butler who admitted the ladies into a lofty hall, whence rose an imposing flight of stairs, was so majestic that Arabella felt almost inclined to apologize for putting him to the trouble of announcing her to her godmother. But she was relieved to find that he was supported by only one footman, and so was able to follow him up with tolerable composure to the drawing-room on the first floor.

Here her qualms were put to flight by the welcome she received. Lady Bridlington, whose plump, pink cheeks were wreathed in smiles, clasped her to an ample bosom, kissed her repeatedly, exclaimed, just as Aunt Emma had, on her likeness to her Mama, and seemed so unaffectedly glad to see her that all constraint was at an end. Lady Bridlington’s good-nature extended even to the governess, to whom she spoke with kindness, and perfect civility.

When Mama had known Lady Bridlington, she had been a pretty girl, without more than commonsense, but with such a respectable portion, and with so much vivacity and good-humour, that it was no surprise to her friends when she contracted a very eligible match. Time had done more to enlarge her figure than her mind, and it was not many days before her young charge had discovered that under a superficial worldly wisdom there was little but a vast amount of silliness. Her ladyship read whatever new work of prose or verse was in fashion, understood one word in ten of it, and prattled of the whole; doted on the most admired singers at the Opera, but secretly preferred the ballet; vowed there had never been anything to equal Kean’s Hamlet on the English stage, but derived considerably more enjoyment from the farce which followed this soul-stirring performance. She was incapable of humming a tune correctly, but never failed to patronize the Concerts of Ancient Music during the season, just as she never failed to visit the Royal Academy every year, at Somerset House, where, although her notion of a good-picture was a painting that reminded her forcibly of some person or place with which she was familiar, she unerringly detected the hand of a master in all the most distinguished artists’ canvasses. Her life seemed to a slightly shocked Arabella to consist wholly of pleasure; and the greatest exertion she ever put her mind to was the securing of her own comfort. But it would have been unjust to have called her a selfish woman. Her disposition was kindly; she liked the people round her to be as happy as she was herself, for that made them cheerful, and she disliked long faces; she paid her servants well, and always remembered to thank them for any extraordinary service they performed for her, such as walking her horses up and down Bond Street in the rain for an hour while she shopped, or sitting up till four or five in the morning to put her to bed after an evening-party; and provided she was not expected to put herself out for them, or to do anything disagreeable, she was both kind and generous to her friends.

She expected nothing but pleasure from Arabella’s visit, and although she knew that in launching the girl into society she was behaving in a very handsome way, she never dwelled on the reflection, except once or twice a day in the privacy of her dressing-room, and then not in any grudging spirit, but merely for the gratifying sensation it gave her of being a benevolent person. She was very fond of visiting, shopping, and spectacles; liked entertaining large gatherings in her own house; and was seldom bored by even the dullest Assembly. Naturally, since every woman of fashion did so, she complained of dreadful squeezes or sadly insipid evenings, but no one who had seen her at these functions, greeting a multitude of acquaintances, exchanging the latest on-dits,closely scanning the newest fashions, or taking eager part in a rubber of whist, could have doubted her real and simple enjoyment of them.

To be obliged, then, to chaperon a young lady making her debut to a succession of balls, routs, Assemblies, Military Reviews, balloon ascensions, and every other diversion likely to be offered to society during the season, exactly suited her disposition. She spent the better part of Arabella’s first evening in Park Street in describing to her all the delightful plans she had been making for her amusement, and could scarcely wait for Miss Blackburn’s departure next day before ordering her carriage to be sent round, and taking Arabella on a tour of all the smartest shops in London.

These cast the shops of High Harrowgate into the shade. Arabella was obliged to exercise great self-restraint when she saw the alluring wares displayed in the windows. She was helped a little by her north-country shrewdness, which recoiled from trifles priced at five times their worth, and not at all by her cicerone who, having been blessed all her life with sufficient means to enable her to purchase whatever took her fancy, could not understand why Arabella would not buy a bronze-green velvet hat, trimmed with feathers and a broad fall of lace, and priced at a figure which would have covered the cost of all the hats so cleverly contrived by Mama’s and Sophia’s neat fingers. Lady Bridlington owned that it was an expensive hat, but she held that to buy what became one so admirably could not be termed an extravagance. But Arabella put it resolutely aside, saying that she had as many hats as she required, and explaining frankly that she must not spend her money too freely, since Papa and Mama could not afford to send her any more. Lady Bridlington was quite distressed to think that such a pretty girl should not be able to set her beauty off to the best ad-vantage. It seemed so sad that she was moved to purchase a net stocking-purse, and a branch of artificial flowers, and to bestow them on Arabella. She hesitated for a few minutes over a handsome shawl of Norwich silk, but it was priced at twenty guineas, and although this could not be said to be a high price, she remembered that she had one herself, a much better one, for which she had paid fifty guineas, which she could very well lend to Arabella whenever she did not wish to wear it herself. Besides, there would be all the expense of Arabella’s Court dress to be borne later in the season, and even though a great deal might be found in her own wardrobe which could be converted to Arabella’s needs, the cost was still certain to be heavy. A further inspection of the shawl convinced her that it was of poor quality, not at all the sort of thing she would like to give her young charge, so they left the shop without buying it. Arabella was profoundly relieved, for although she would naturally have liked to have possessed the shawl, it made her very uncomfortable to be in danger of costing her hostess so much money.

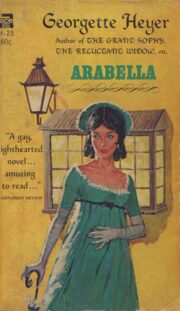

"Arabella" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Arabella". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Arabella" друзьям в соцсетях.