Her frankness in speaking of her circumstances made Lady Bridlington a little thoughtful. She did not immediately mention the matter, but when the two ladies sat before the fire in the small saloon that evening, drinking tea, she ventured to put into words some at least of the thoughts which were revolving in her head.

“You know, my dear,” she said, “I have been considering the best way to set to work, and I have made up my mind to it that as soon as you have grown more used to London—and I am sure it will not be long, for you are such a bright, clever little puss!—I should introduce you, quietly, you know! The season—has not yet begun, and London is still very thin of company. And I think that will suit us very well, for you are not used to the way we go on here, and a small Assembly—no dancing, just an evening-party, with music, perhaps, and cards—is the very thing for your first appearance! I mean to invite only a few of my friends, the very people who may be useful to you. You will become acquainted with some other young ladies, and of course with some gentlemen, and that will make it more comfortable, I assure you, when I take you to Almack’s, or to some large ball. Nothing can be more disagreeable than to find oneself in a gathering where one does not recognize a single face!”

Arabella could readily believe it, and had nothing but approbation for this excellent scheme. “Oh, yes, if you please, ma’am! It is of all things what I should like, for I know I shall not know how to go on at first, though I mean to learn as fast as I can!”

“Exactly so!” beamed her ladyship. “You are a sensible girl, Arabella, and I am very hopeful of settling you respectably, just as I promised your Mama I would!” She saw that Arabella was blushing, and added: “You won’t object to my speaking plain, my love, for I daresay you know how important it is that you should be creditably established. Eight children! I do not know how your poor Mama will ever contrive to get good husbands for your sisters! And boys are such a charge on one’s purse! I am sure I do not care to think of what my dear Frederick cost his father and me from the first to last! First it was one thing, and then another!”

A serious look came into Arabella’s face, as she thought of the many and varied needs of her brothers and sisters. She said earnestly: “Indeed, ma’am, what you say is very just, and I mean to do my best not to disappoint Mama!”

Lady Bridlington leaned forward to lay her pudgy little hand over Arabella’s, and to squeeze it fondly. “I knew you would feel just as you ought!” she said. “Which brings me to what I had in mind to say to you!” She sat back again in her chair, fidgeted for a moment with the fringe of her shawl, and then said without looking at Arabella: “You know, my love, everything depends on first impressions—at least, a great deal does! In society, with everyone trying to find eligible husbands for their daughters, and so many beautiful girls for the gentlemen to choose from, it is in the highest degree important that you should do and say exactly what is right. That is why I mean to bring you out quietly, and not at all until you feel yourself at home in London. For you must know, my dear, that only rustics appear amazed. I am sure I do not know why it should be so, but you may believe that innocent girls from the country are not at all what the gentlemen like!”

Arabella was surprised, for her reading had taught her otherwise. She ventured to say as much, but Lady Bridlington shook her head. “No, my love, it is not so at all! That sort of thing may do very well in a novel, and I am very fond of novels myself, but they have nothing to do with life, depend upon it! But that was not what I wished to say!” Again she played with the shawl-fringe, saying in a little burst of eloquence: “I would not, if I were you, my dear, be forever talking about Heythram, and the Vicarage! You must remember that nothing is more wearisome than to be obliged to listen to stories about a set of persons one has never seen. And though of course you would not prevaricate in any way, it is quite unnecessary to tell everyone—or, indeed, anyone!—of your dear Papa’s situation! I have said nothing to lead anyone to suppose that he is not in affluent circumstances, for nothing, I do assure you, Arabella, could be more fatal to your chances than to have it known that your expectations are very small!”

Arabella was about to reply rather more hotly than was civil when the recollection of her own conduct in Mr. Beaumaris’s house came into her mind with stunning effect. She hung her head, and sat silent, wondering whether she ought to make a clean breast of the regrettable affair to Lady Bridlington, and deciding that it was too bad to be spoken of.

Lady Bridlington, misunderstanding the reason for her evident confusion, said hastily: “If you should be fortunate enough to engage some gentleman’s affection, dear Arabella, of course you will tell him just how you are placed, or I shall, and—and, depend upon it, he will not care a button! You must not be thinking that I wish you to practise the least deception, for it is no such thing! Merely, it would be foolish, and quite unnecessary, for you to be talking of your circumstances to every chance-met acquaintance!”

“Very well, ma’am,” said Arabella, in a subdued tone.

“I knew you would be sensible! Well, now, I am sure there is no need for me to say anything more to you on this head, and we must decide whom I shall invite to my evening-party. I wonder, my love, if you would see if my tablets are on that little table. And a pencil, if you will be so good!”

These commodities having been found, the good lady settled down happily to plan her forthcoming party. Since the names she recited were all of them unknown to Arabella, the discussion resolved itself into a gentle monologue. Lady Bridlington ran through the greater part of her acquaintance, murmuring that it would be useless to invite the Farnworths, since they had no children; that Lady Kirkmichael gave the shabbiest entertainments, and could not be depended on to invite Arabella, even if she did decide to give a ball for that lanky daughter of hers; that the Accringtons must of course be sent a card, and also the Buxtons—delightful families, both, and bound to entertain largely this season! “And I mean to invite Lord Dewsbury, and Sir Geoffrey Morcambe, my dear, for there is no saying but what one of them might—And I am sure Mr. Pocklington has been hanging out for a wife these two years, not but what he is perhaps a little old—However, we will ask him to come, for there can be no harm in that! Then, I must certainly prevail upon dear Lady Sefton to come, for she is one of the patronesses of Almack’s, you know; and perhaps Emily Cowper might—And the Charnwoods, and Mr. Catwick; and, if they are in town, the Garthorpes ...”

She rambled on in this style, while Arabella tried to appear interested. But as she could do no more than agree with her hostess when she was appealed to, her attention soon wandered, to be recalled with a jerk when Lady Bridlington mentioned a name she did know.

“And I shall send Mr. Beaumaris a card, because it would be such a splendid thing for you, my love, if it were known that he came to your debut—for such we may call it! Why, if he were to come, and perhaps talk to you for a few minutes, and seem pleased with you, you would be made, my dear! Everyone follows his lead! And perhaps, as there are so few parties yet, he might come! I am sure I have been acquainted with him for years, and I knew his mother quite well! She was Lady Mary Caldicot, you know: a daughter of the late Duke of Wigan, and such a beautiful creature! And it is not as though Mr. Beaumaris has never been to my house, for he once came to an Assembly here, and stayed for quite half-an-hour! Mind, we must not build upon his accepting, but we need not despair!”

She paused for breath, and Arabella, colouring in spite of herself, was able at last to say: “I—I am myself a little acquainted with Mr. Beaumaris, ma’am.”

Lady Bridlington was so much astonished that she dropped her pencil. “Acquainted with Mr. Beaumaris?” she repeated. “My love, what can you be thinking about? When can you possibly have met him?”

“I—I quite forgot to tell you, ma’am,” faltered Arabella unhappily, “that when the pole broke—I told you that!—Miss Blackburn and I sought shelter in his hunting-box, and—and he had Lord Fleetwood with him, and we stayed to dine!”

Lady Bridlington gasped. “Good God, Arabella, and you never told me! Mr. Beaumaris’s house! He actually asked you to dine, and you never breathed a word of it to me!”

Arabella found herself quite incapable of explaining why she had been shy of mentioning this episode. She stammered that it had slipped out of her mind in all the excitement of coming to London.

“Slipped out of your mind?” exclaimed Lady Bridlington. “You dine with Mr. Beaumaris, and at his hunting-box, too, and then talk to me about the excitement of coming to London? Good gracious, child—But, there, you are such a country-mouse, my love, I daresay you did not know all it might mean to you! Did he seem pleased? Did he like you?”

This was a little too much, even for a young lady determined to be on her best behaviour. “I daresay he disliked me excessively, ma’am, for I thought him very proud and disagreeable, and I hope you won’t ask him to your party on my account!”

“Not ask him to my party, when, if he came to it, everyone would say it was a success! You must be mad, Arabella, to talk so! And do let me beg of you, my dear, never to say such a thing of Mr. Beaumaris in public! I daresay he may be a little stiff, but what is that to the purpose, pray? There is no one who counts for more in society, for setting aside his fortune, which is immense, my love, he is related to half the houses in England! The Beaumarises are one of the oldest of our families, while on his mother’s side he is a grandson of the Duchess of Wigan—the Dowager Duchess, I mean, which of course makes him cousin to the present Duke, besides the Wainfleets, and—But you would not know!” she ended despairingly.

“I thought Lord Fleetwood most amiable, and gentlemanlike,” offered Arabella, by way of palliative.

“Fleetwood! I can tell you this, Arabella: there is no use in your setting your cap at him, for all the world knows that he must marry money!”

“I hope, ma’am,” cried Arabella, flaring up, “that you do not mean to suggest that I should set my cap at Mr. Beaumaris, for nothing would prevail upon me to do so!”

“My love,” responded Lady Bridlington frankly, “it would be quite useless for you to do so! Robert Beaumaris may have his pick of all the beauties in England, I daresay! And, what is more, he is the most accomplished flirt in London! But I do most earnestly implore you not to set him against you by treating him with the least incivility! You may think him what you please, but, believe me, Arabella, he could rain your whole career—and mine, too, if it came to that!” she added feelingly.

Arabella propped her chin in her hand, pondering an agreeable thought. “Or he could make everything easy for me, ma’am?” she enquired.

“Of course he could—if he chose to do it! He is the most unpredictable creature! It might amuse him to make you the rage of town—or he might take it into his head to say you were not quite in his style—and if once he says that, my dear, what man will look twice at you, unless he has already fallen in love with you, which, after all, we cannot expect?”

“My dear ma’am,” said Arabella, in dulcet accents, “I hope I should not be so ill-bred as to be uncivil to anyone—even Mr. Beaumaris!”

“Well, my dear, I hope not, indeed!” said her ladyship doubtfully.

“I promise I will not be in the least degree uncivil to Mr. Beaumaris. if he should come to your party,” said Arabella.

“I am happy to hear you say so, my love, but ten to one he won’t come,” responded her ladyship pessimistically.

“He said to me at parting that he hoped to have the pleasure of calling on me in town before many days,” said Arabella disinterestedly.

Lady Bridlington considered this, but in the end shook her head. “I do not think we should set any store by that,” she said. “Very likely he said it for politeness’ sake.”

“Very likely,” agreed Arabella. “But if you are acquainted with him, I wish you will send Lord Fleetwood a card for your party, ma’am, for he was excessively kind, and I liked him.”

“Of course I am acquainted with him!” declared Lady Bridlington, quite affronted. “But do not be setting your heart on him., Arabella, I beg of you! A delightful rattle, but the Fleetwoods are all to pieces, by what I hear, and however much he may flirt with you, I am persuaded he will never make you an offer!”

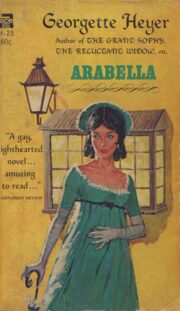

"Arabella" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Arabella". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Arabella" друзьям в соцсетях.