“Lord, yes!” he agreed, with a shudder. “But it won’t come to that! If anyone asks me any prying questions, I shall say you are well known to me, and so will Felix!”

“Yes, but that is not all!” Arabella pointed out. “I can never, never accept any offer made to me, and what Mama will think of such selfishness I dare not consider! For she so much hoped that I should form an eligible connection, and Lady Bridlington is bound to tell her that—that quite a number of very eligible gentlemen have paid me the most marked attentions!”

Bertram knit his brows over this. “Unless—No, you’re right, Bella; devilish awkward fix! You would have to tell the truth, if you accepted an offer, and ten to one he’d cry off. What a tiresome girl you are, to be sure! Dashed if I see what’s to be done! Do you, Felix?”

“Very difficult situation,” responded Mr. Scunthorpe, shaking his head. “Only one thing to be done.”

“What’s that?”

Mr. Scunthorpe gave a diffident cough. “Just a little thing that occurred to me. Daresay you won’t care about it: can’t say I care about it myself, but can’t hang back when a lady’s in a fix.”

“But what is it?”

“Mind, only a notion I had!” Mr. Scunthorpe warned him. “You don’t like it: you say so! I don’t like it, but ought to offer.” He perceived that the Tallants were quite mystified, blushed darkly, and uttered in a strangled voice; “Marriage!”

Arabella stared at him for a moment, and then went into a peal of mirth. Bertram said scornfully: “Of all the cork-brained notions—! You don’t want to marry Bella!”

“No,” conceded Mr. Scunthorpe. “Promised I would help her out of the scrape, though!”

“What’s more,” Bertram said severely, “those trustees of yours would never let you! You’re not of age.”

“Talk them over,” said Mr. Scunthorpe hopefully.

However. Arabella, thanking him for his kind offer, said that she did not think they would suit. He seemed grateful, and relapsed into the silence which appeared to be natural to him.

“I daresay I shall hit upon something,” said Bertram. “I’ll think about it, at all events. Should I stay to do the pretty to this godmother of yours, do you think?”

Arabella urged him strongly to do so. She was inclined to grieve over his necessary incognito, but he told her frankly that it would not at all suit him to be for ever gallanting her to the ton parties. “Very dull work!” he said. “I know you are gone civility-mad since you came to town, but it’s not in my line.” He then enumerated the sights he meant to see in London, and since these seemed to consist mostly of such inocuous entertainments as Astley’s Amphitheatre, the Royal Menagerie at the Tower, Madame Tussaud’s Waxworks, a look-in at Tattersall’s, the departure of the Brighton coaches from the White Horse Cellar, and the forthcoming Military Review in Hyde Park, his anxious sister’s worst qualms were allayed. At first sight he had seemed to her to have grown a great deal older, for he was wearing a sophisticated waistcoat, and had brushed his hair in a new style; but when he told her about the peep-show which had diverted him so much in Coventry Street, and expressed a purely youthful desire to witness that grand spectacle, The Burning of Moscow (supported by Tight-rope Walking, and an Esquestrian Display) she could feel that he was still boy enough not to hanker after the more sophisticated and by far more dangerous amusements to be found in London. But, then, as he confidentially informed Mr. Scunthorpe, when they presently left Park Street together, females took such foolish notions into their heads that it would have been ridiculous to have disclosed to her that he had an equally ardent desire to see a bout of fisticuffs at the Fives-court, to blow a cloud with all the Corinthians at the Daffy Club, to penetrate the mysteries of the Royal Saloon, and the Peerless Pool, and certainly to put in an appearance at the Opera—not, he hastened to assure his friend, because he wanted to listen to music, but because he was credibly informed that to stroll in the Fops’ Alley was famous sport, and all the go. Since he had decided, very prudently, to put up at one of the City inns, where, if he chose, he could be sure of a tolerable dinner at the Ordinary, which was very moderately priced, he entertained reasonable hopes of being able to afford all these diversions. But first, he perceived, it was necessary to buy a much higher-crowned and more curly-brimmed beaver to set on his head; a pair of Hessians with tassels; a fob, and perhaps a seal; and certainly a pair of natty yellow gloves. Without these adjuncts to a gentleman’s costume he would look like a Johnny Raw. Mr. Scunthorpe agreed, and ventured to point out that a driving-coat with only two shoulder-capes was thought, in well-dressed circles, to be a paltry affair. He said he would take Bertram along to his own man, a devilish clever tailor, even though he had not acquired the fame of a Weston or a Stultz. However, as the great advantage of patronizing this rising man lay in the assurance that he would be willing to rig out any friend of Mr. Scunthorpe’s on tick, Bertram raised no objection to jumping into a hackney at once, and telling the jarvey to drive with all speed to Clifford Street. Mr. Scunthorpe vouched for it that Swindon’s art would give his friend quite a new touch, and as this seemed extremely desirable to Bertram, he thought he could hardly lay out a substantial sum of money to better advantage. Mr. Scunthorpe then imparted to him a few useful hints,. particularly warning him against such extravagances of style as must give rise to the suspicion that he belonged to the extreme dandy-set frowned upon by the real Pinks of the Ton. Beyond question, the finest model for any aspiring gentleman to copy was the Nonpareil, that Go amongst the Goers. This put Bertram in mind of something which had been slightly troubling his mind, and he said: “I say, Felix, do you think my sister should be driving about the town with him? I don’t mind telling you I don’t like it above half!”

Here Mr. Scunthorpe was able at once to allay his qualms: for a lady to drive in a curricle or a phaeton, with a groom riding behind, was unexceptionable. “Mind, it would not do for a female to go in a tilbury!” he said.

His brotherly concern relieved, Bertram abandoned the question, merely remarking that he would give a monkey to see his father’s face if he knew how racketty Bella had become.

Arrived in Clifford Street, they obtained instant audience of Mr. Swindon, who was so obliging as to bring out his pattern-card immediately, and to advise his new client on the respective merits of Superfine and Bath Suiting. He thought six capes would be sufficient for a light drab driving-coat, an opinion in which Mr. Scunthorpe gravely concurred, explaining to Bertram that it would never do for him to ape the Goldfinches, with their row upon row of capes. Unless one was an acknowledged Nonesuch, capable of driving to an inch, or one of the Melton men, it was wiser, he said, to aim at neatness and propriety rather than the very height of fashion. He then bent his mind to the selection of a cloth for a coat, he was persuaded to do so, as much by the assertion of Mr. Swindon that a single-breasted garment of corbeau-coloured cloth, with wide lapels, and silver buttons, would set his person off to advantage, as by the whispered assurance of his friend that the snyder always gave his clients long credit. Indeed, Mr. Scunthorpe was rarely troubled with his tailor’s account, since that astute man of business was well aware that being a fatherless minor Mr. Scunthorpe’s considerable fortune was held in trust by tight-fisted guardians, who doled him out a beggarly allowance. Nothing so ungenteel as cost or payment was mentioned during the session in Clifford Street, so that Bertram left the premises torn between relief and a fear that he might have pledged his credit for a larger sum than he could afford to pay. But the novelty and excitement of a first visit to the Metropolis soon put such untimely thoughts to route, while a lucky bet at the Fives-court clearly showed the novice the easiest way of raising the wind.

A close inspection of such sprigs of fashion as were to be seen at the Fives-court made Bertram very glad to think he had bespoken a new coat, and he confided to Mr. Scunthorpe that he would not visit the haunts of fashion until his clothes had been sent home. Mr. Scunthorpe thought this a wise decision, and, as it was of course absurd to suppose that Bertram should kick his heels at the City inn which enjoyed his patronage, he volunteered to show him how an evening full of fun and gig could be spent in less exalted circles. This entertainment, beginning as it did in the Westminster Pit, where it seemed to the staring Bertram that representatives of every class of society, from the Corinthian to the dustman, had assembled to watch a contest between two dogs; and proceeding by way of the shops of Tothill Fields, where adventurous bucks tossed off noggins of Blue Ruin, or bumpers of heavy wet, in company with bruisers, prigs, coal-heavers, Nuns, Abbesses, and apple-women, to a coffee-shop, ended in the watch-house, Mr. Scunthorpe having become bellicose under the influence of his potations. Bertram, quite unused to such quantities of liquor as he had imbibed, was too much fuddled to have any very clear notion of what circumstance it was that had excited his friend’s wrath, though he had a vague idea that it was in some way connected with the advances being made by a gentleman in Petersham trousers towards a lady who had terrified him earlier in the proceedings by laying a palpable lure for him. But when a mill was in progress it was not his part to enquire into the cause of it, but to enter into the fray in support of his cicerone. Since he was by no means unlearned in the noble art of self-defence, he was able to render yeoman service to Mr. Scunthorpe, no proficient, and was in a fair way to milling his way out of the shop when the watch, in the shape of several Charleys, all springing their rattles, burst in upon them and, after a spirited set-to, over-powered the two peacebreakers, and hailed them off to the watch-house. Here, after considerable parley, conducted for the defence by the experienced Mr. Scunthorpe, they were admitted to bail, and warned to present themselves next day in Bow Street, not a moment later than twelve o’clock. The night-constable then packed them both into a hackney, and they drove to Mr. Scunthorpe’s lodging in Clarges Street, where Bertram passed what little was left of the night on the sofa in his friend’s sitting-room. He awoke later with a splitting headache, no very clear recollection of the late happenings, but a lively dread of the possible consequences of what he feared had been a very bosky evening. However, when Mr. Scunthorpe’s man had revived his master, and he emerged from his bedchamber, he was soon able to allay any such misgivings. “Nothing to be in a fret for, dear boy!” he said. “Been piloted to the lighthouse scores of times! Watchman will produce broken lantern in evidence—they always do it!—you give false name, pay fine, and all’s right!”

So, indeed, it proved, but the experience a little shocked the Vicar’s son. This, coupled with the extremely unpleasant after-effects of drinking innumerable flashes of lightning, made him determine to be more circumspect in future. He spent several days in pursuing such harmless amusements as witnessing a badger drawn in a menagerie in Holborn, losing his heart to Miss O’Neill from a safe position in the pit, and being introduced by Mr. Scunthorpe into Gentleman Jackson’s exclusive Boxing School in Bond Street. Here he was much impressed by the manners and dignity of the proprietor (whose decision in all matters of sport, Mr. Scunthorpe informed him, was accepted as final by patrician and plebeian alike), and was gratified by a glimpse of such notable amateurs as Mr. Beaumaris, Lord Fleetwood, young Mr. Terrington, and Lord Withernsea. He had a little practise with the single-stick with one of Jackson’s assistants, felt himself honoured by receiving a smiling word of encouragement from the great Jackson himself, and envied the assurance of the Goers who strolled in, exchanged jests with Jackson, who treated them with the same degree of civility as he showed to his less exalted pupils, and actually enjoyed bouts with the ex-champion himself. He was quick to see that no consideration of rank or consequence was enough to induce Jackson to allow a client to plant a hit upon his person, unless his prowess deserved such a reward; and from having entered the saloon with a feeling of superiority he swiftly reached the realization that in the Corinthian world excellence counted for more than lineage. He heard Jackson say chidingly to the great Nonpareil himself (who stripped to remarkable advantage, he noticed) that he was out of training; and from that moment his highest ambition was to put on the gloves with this peerless master of the art.

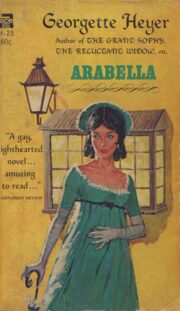

"Arabella" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Arabella". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Arabella" друзьям в соцсетях.