The buffet included clam chowder, mussels, grilled linguiça, corn on the cob, and a pile of steaming scarlet lobsters served whole. Ann had doubts about her lobster-cracking ability; she worried about lobster guts messing the front of her dress. There were plastic bibs on the tables, but the last thing Ann wanted was to be seen wearing one.

Ahead of her, Chance loaded his plate with mussels. He turned to Ann. “I’ve never had mussels before.”

“They’re yummy, you’ll love them,” she said, which was a glib thing to say, as, living three hours from the coast, she ate mussels about once every decade.

Chance pulled one from its shell and popped it into his mouth. He nodded his head. “Interesting texture,” he said.

Ann searched the party for the yellow of Helen’s dress. She spied Helen out on the patio, talking to Stuart.

Ann had been forced to swallow a whole bunch of unpleasant facts in the past twenty years, but the worst thing was that, for a time, Helen had been a stepmother to her children. Helen had coparented them every third weekend with Jim. Ann used to question the boys when they got home from weekends with their father and Helen. What had they done? What had they eaten? Had they gone out or stayed in? Did Helen cook? Did Helen read to them at night? Did Helen let them stay up late to watch R-rated movies? Did Helen kiss them good-bye before they piled into Jim’s car at seven o’clock on Sunday evening?

What Ann had gleaned was that, in those years, Jim took on most of the duties pertaining to the three older boys, while Helen cared for Chance. Chance had been a colicky baby, Helen carried him everywhere in a sling, Chance didn’t sleep in a crib, he slept in the bed with Helen and Jim. Chance had walked early, and Helen was forever chasing him around. Helen had made chicken with biscuits once, but the biscuits were burned. (In Roanoke, Ann knew, Helen had grown up with a black housekeeper who had done all the cooking.) Jim often took the boys to McDonald’s for lunch, which was a treat for them, since Ann was sponsoring an initiative for healthier eating habits for Carolina schoolchildren and hence did not allow the kids fast food. Helen bought the boys Entenmann’s coffee cake for breakfast and let them eat it straight from the box in front of the TV on Saturday mornings. Helen sometimes yelled at the boys-or even at Jim-to help out more. Jim took the boys to the Flying Burrito for Mexican food on Sunday nights before bringing them back to Ann, and Helen and Chance always stayed home.

Ann tucked every piece of information away. To her credit, she had never demonized Helen to the boys. But she had lived in mortal fear that the boys would one day arrive home, announcing that they liked Helen better.

Just the way that Jim had once announced he liked Helen better.

It took a moment for Ann to realize that Chance was in distress. He dropped his plate on the floor, where it broke in half, and the mussel shells scattered everywhere. Ann jumped out of the way. Then she saw Chance clutching at his throat; he was puffing up, turning the color of raw meat.

“Help!” Ann shouted. She spun around, hoping to find Jim, but behind her was a stout, bald man with square glasses and a bullfrog neck. “Help him!”

A commotion ensued. Chance sank to his knees. The man behind Ann rushed to his side.

“We need an EpiPen!” he shouted. “He’s having an allergic reaction!”

Ann snatched her phone out of her purse and dialed 911. She said, “Nantucket Yacht Club, nineteen-year-old male, severe allergic reaction. Please send an ambulance! His throat is closing!”

Chance was clawing at his neck, gasping for air in a way that made it look like he was drowning right in front of them. He sought out Ann’s face; his eyes were bulging. Ann was hot with panic. She was shaking, she thought, My God, what if he dies? But then her mothering instincts kicked in. She knelt beside him.

“I’ve called an ambulance, Chance,” she said. “Help is coming.”

One of the club’s managers shot through the kitchen’s double doors holding a first aid kit, from which he pulled an EpiPen. He stabbed Chance in the thigh.

Suddenly Jim was there. “Jesus Christ!” he said. “What the hell?”

“He ate a mussel,” Ann said. “He must be allergic. He swelled right up.” It had reminded Ann of the scene from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory where Violet turns into a blueberry and the Oompa-Loompas roll her away.

And then Ann saw a flash of yellow.

“Chancey!” Helen screamed.

The epinephrine seemed to help. Chance’s color didn’t improve, but neither did it deepen, and he was still forcing wheezing breaths in and out. A crowd gathered, and urgent queries of What happened? and Who is it? circulated. Ann heard someone say, “It’s Stuart’s stepbrother,” then someone else say, “It’s the other woman’s son.” Ann turned around and to no one in particular said, “His name is Chance Graham, and he’s the groom’s half brother.”

Jim and the yacht club manager kept imploring people to back up so that Chance could have some air. Helen was kneeling by Chance’s head, smoothing his hair, patting his mottled cheeks. She seemed elegant and glamorous, even on her knees. She looked up at Ann. “What did he eat?” she demanded.

The question was nearly accusatory, as though Ann were somehow to blame. She felt like the wicked stepmother who had given him a poison apple.

“He ate a mussel,” Ann said.

Helen returned her attention to Chance, and Ann felt a creeping sense of shame. Chance had said he’d never eaten a mussel before, and Ann had said, They’re yummy, you’ll love them. She hadn’t told him to eat it; he had tried it of his own volition. But she also hadn’t given him a warning about allergies. She hadn’t even considered allergies. Hadn’t Chance been allergic to milk as a child? Ann thought she recalled hearing that, but she wasn’t positive. He wasn’t her child. But lots of people were allergic to shellfish. Should she have warned him instead of encouraging him?

The paramedics stormed in, all black uniforms and squawking police scanners. The lead paramedic was a woman in her twenties with wide hips and a brown ponytail. “What’d he eat?”

“A mussel,” Helen said.

There was talk and fussing, another shot of something, an oxygen mask. They lifted Chance onto a gurney.

Helen said, “May I ride in the ambulance?”

“You’re his mother?” the paramedic asked.

“And I’m his father,” Jim said. Jim and Helen were now standing side by side, unified in their roles as Chance’s parents.

“No family in the ambulance. You can follow us to the hospital.”

“Oh, please,” Helen said. “He’s only a teenager. Please let me come in the ambulance.”

“Sorry, ma’am,” the paramedic said. They whisked Chance down the hall and out the front doors.

Helen gazed at Jim-in her heels, she was nearly as tall as he was-and burst into tears. Ann watched Jim fight what must have been a dozen conflicting emotions. Did he want to comfort her? Ann wondered.

He patted her shoulder. “He’ll be fine,” Jim said.

“We have to go to the hospital,” Helen said. “Can I get a ride with y’all?”

“Okay,” Jim said. He took Ann by the shoulder. “Let’s go.”

Ann hesitated. An old, dark emotion bubbled up in her, as thick and viscous as tar. She didn’t want to go anywhere with Jim and Helen. She would be an outsider; she wasn’t Chance’s mother. She loved Chance and was sick with worry, but she didn’t belong at the hospital with Jim and Helen. However, she didn’t want Jim and Helen to go without her, either. She couldn’t decide what to do. It was an impossible situation.

Suddenly Stuart and Ryan and H.W. were upon her. “Mom?” Ryan said. He circled his arm around her shoulders.

Stuart said, “Is he going to be okay?”

Jim said, “Your mother and I are going to the hospital with Helen.”

“Actually, I’m going to stay here,” Ann said. To Jim she said, “You go. Please keep me posted.”

“What?” Jim said.

Helen shifted from foot to foot. “Can we please leave?”

“Go,” Ann said. She gave Jim’s arm a push.

“Would you stop acting like a child?” he whispered.

“I need to stay here,” Ann said. “It’s the rehearsal dinner. It’s Stuart’s wedding.” These words sounded reasonable to her ears, but was she acting like a child? She didn’t want to be a third wheel with Jim and Helen. She didn’t want to have to watch them together in their roles as Mom and Dad. She hated them both at that moment; she hated what they’d done to her. She couldn’t believe that she had somehow thought having Helen at the wedding would be a healing experience. It was turning out to be the opposite of healing.

“Ann,” Jim said. “Please come. I need you.”

Ann smiled her senatorial smile. “I’m going to represent here. You go, and let me know how he’s doing.” She took Ryan’s arm and headed back into the party.

Ryan put his hand on her lower back and whispered in her ear, “Well done, Mother. As always.”

Ann fixed herself a plate of food and went to sit with the Lewises, the Cohens, and the Shelbys. On the way, she stopped at each table-most of them filled with people she didn’t know-and reassured everyone that Chance would be fine, he was on his way to the hospital to get checked out. As a politician, Ann had spent her career managing crises; the soothing smiles and words and gestures came naturally to her. She wouldn’t let herself think about Helen and Jim side by side in the front seat of the rental car, or about how Helen’s intoxicating perfume would linger there for Ann and Jim to smell every time they opened the door and climbed in.

Violet, you’re turning violet. All the nights that Ann had read Charlie and the Chocolate Factory to her boys, Jim had been living in Brightleaf Square making love to the woman he was now driving to the hospital.

Ann closed her eyes against the vision, but all she saw was yellow.

Ann sat next to Olivia, who squeezed the heck out of Ann’s forearm but said nothing except “I’m sure he’ll be fine.”

“Of course he’ll be fine,” Ann said. She beamed vacantly at her friends, all of whom were wearing plastic bibs and attacking their lobsters. The conversation turned to allergic reactions that people had witnessed or merely heard of secondhand-a man going comatose over his bowl of New England clam chowder, a fifteen-year-old girl dying because she kissed her boyfriend, who had eaten peanut butter for lunch. Meanwhile, in the background, the orchestra played “Mack the Knife” and “Fly Me to the Moon.” Couples danced. Stuart and Jenna got up to dance, and there was a smattering of applause. Those two made such a sweet, earnest, clean-cut, wholesome, good-looking couple. Thank God Stuart had broken up with She Who Shall Not Be Named. When Ann used to gaze upon Stuart and Crissy Pine, she had had visions of expensive vacations and overindulged children; she imagined Stuart trapped in a soulless McMansion with a perpetually unhappy wife. Stuart and Jenna’s union would be meaningful and strong; they would live with a social conscience, serve on nonprofit boards, and be role models, envied by their friends and neighbors.

Ann picked at a boiled red-skinned potato. Yes, it all looked good from here, but who knew what would happen.

The Cohens got up to dance, and Ann buttered a roll that she had no intention of eating. She checked her cell phone: nothing. Jim and Helen would be at the hospital by now. They would be sitting in the waiting room together, awaiting news. People who saw them would think they were a couple.

Tap on the shoulder. Jethro.

“Dance with me,” he said.

“I don’t feel up to it,” Ann said.

“You have to,” Jethro said. “You need to show these northerners you didn’t bring me along as chattel.”

Ann made a face. “Please spare me the self-deprecating black humor.” But Ann then admitted she was powerless to resist Jethro under any circumstances. “Only you,” she said.

She accepted his hand and followed him to the dance floor, where he swung her expertly around. Ann and Jim had taken dance lessons right after getting married the second time; it was one of the things they’d made an effort to do together, along with couples Bible study, and antiquing in Asheville, and trout fishing on the Eno River in a flat-bottomed rowboat Jim had bought. They had been happy the second time. Happy until thirty minutes ago. Now Ann could feel herself cracking inside, a ravine opening up.

The song ended. She and Jethro clapped. She kissed his cheek. Ryan had told Ann and Jim that he was gay during Thanksgiving break of his freshman year in college. Ann would say she had handled it well. It wasn’t exactly her wish for him, only because she feared his life would be difficult-and of course there was the issue of grandchildren. Jim had taken the news in stride. He had said, “I’m in no position to judge you, son. But for crying out loud, be careful.” Ann hadn’t been able to predict then how she would adore her son’s future boyfriend. She felt even closer to Jethro than she did to Jenna.

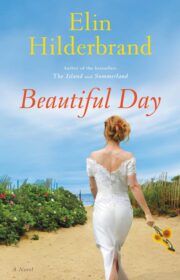

"Beautiful Day" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Beautiful Day". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Beautiful Day" друзьям в соцсетях.