Merlots at the Lewises’.

Sauvignon blancs at the Greenes’.

Ann was desperate to host, and she wanted to do champagnes. Expensive choice, Jim said. Yes, it was expensive, but that was part of the appeal. Ann bought two cases of champagne; most of it she had to special order from the bottle shop: Veuve Clicquot, Taittinger, Moët et Chandon, Perrier-Jouët, Schramsberg, Mumm, Pol Roger. Ann killed herself over the hors d’oeuvres. She toasted and seasoned macadamia nuts; she prepared phyllo triangles with three fillings. She bought five pounds of shrimp cocktail.

A thousand dollars spent, when all was said and done, though she’d never admitted that to Jim.

The night should have been a great success, but from the get-go, things were off-kilter. Helen Oppenheimer showed up alone; Nathaniel was sick, she said. Then Helen proceeded to get very drunk. But really, Ann thought, they all got very drunk. It was something about the nature of champagne, or about the tiny, delicate (insubstantial) hors d’oeuvres Ann had prepared. The evening reached a point where Helen collapsed onto Ann and Jim’s sofa and said, “I’ve been lying to all of you. I’m sorry. Nathaniel isn’t sick. We’ve separated.”

There were expressions of shock followed by sympathy, followed by a lot of confessional talk, all of it too intimate for the nature of their group. However, Ann had willingly participated in it. She found the news of Helen’s separation titillating. It turned out that Helen, who worked in the development office at Fuqua, was desperate for children. And Nathaniel, who was a curator at the North Carolina Museum of Art, refused to have any. Their sex life was a joke, Helen said. In fact, Helen suspected that Nathaniel was gay.

“It’s an irreconcilable difference,” Helen said. “It is THE irreconcilable difference. So I left.”

Ann and the other women agreed that Helen should have left. Helen was young, and so beautiful. She would find somebody else. She would have children.

When the night drew to a close, Helen was… well, if it hadn’t been for her tragic revelation, Ann might have called her a sloppy drunk. She couldn’t drive herself home. Ann volunteered Jim to drive her.

Ann remembered Olivia giving her googly eyes. As in What the hell is wrong with you? But Ann was too drunk herself to pick up on it.

She remembered that Jim had come home whistling.

But at the time, Ann thought nothing of it. She was happy that Helen had felt close enough to the group to reveal the truth. It meant the evening had been a success. And the next day everyone called to thank Ann and tell her it was the best wine tasting yet.

Cabernets at the Fairlees’.

Finally, it was Helen’s turn to host. She had moved out of the house that she had shared with Nathaniel and into one of the brand-new lofts built at Brightleaf Square. She invited everyone over for a port tasting. She would serve only desserts, she said, and cigars for the men.

Ann had been excited to go. She was dying to see what those lofts looked like, and she wanted to support Helen in her new life. It must have been difficult to stay in the wine-tasting group as the only single person among couples. But then Ryan got the chicken pox. On the Saturday of the port tasting, he had a temperature of 103 degrees and was covered in red spots. Jim had offered to stay home and let Ann go. But Ann wouldn’t hear of it. She didn’t really like port anyway, and Helen had made a big deal about the Cuban cigars she had gotten from a friend of hers living in Stockholm. Jim should go. Furthermore, Ryan was a mama’s boy, a trait that became even more pronounced when he was sick. Ann couldn’t imagine Jim staying home to deal with him.

“You go,” Ann said.

“You’re sure?” Jim said. “We could both stay home.”

“No, no, no!” Ann said. “That would make it seem like we’re rejecting Helen.”

“It will not seem like we’re rejecting Helen,” Jim said. “It will seem like our child has the chicken pox.”

“You go,” Ann said. “I insist.”

At the groomsmen’s house, breakfast was devoured, and everyone complimented Ann’s efforts in the kitchen-especially Autumn, who seemed surprisingly at ease with Ann, considering that Autumn was wearing no pants and had spent the night with Ann’s son after knowing him all of six hours. Ann cleared the dishes and began washing them at the sink, until Ryan and Jethro nudged her out of the way and told her to go relax.

Relax? she thought.

She headed upstairs to find Stuart.

Ann often wondered: If Jim had stayed home to take care of Ryan with the chicken pox and Ann had gone to the port tasting at Helen’s new apartment, would any of this have happened?

As it was, Jim went to Helen’s party and returned home at 3:20 in the morning. Ann had fallen asleep a little after ten after giving Ryan a baking soda bath, but she opened one eye to Jim, and the clock, when he climbed into bed. He smelled unfamiliar-like cigar smoke, and something else.

In the morning, Ann asked, “How was the party?”

Jim nodded. “Yep. It was good.”

In the afternoon, Olivia called. She said, “Helen Oppenheimer is trouble. She was all over every man at that party.” She paused. “What time did Jim get home?”

“Oh,” Ann said. “Not late.”

The affair had started that night, or at least that was what Jim confessed later. Ann had her suspicions that something had actually happened when Jim drove Helen home after the champagne party. But Ann had continued on, blissfully unaware, throughout the spring, into the summer.

It was in July that Shell Phillips had called with the idea of hot air ballooning. It could be done near Asheville, in the western part of the state, a four-hour drive away. They would lift off at five in the evening and land just before sunset in a meadow where there would be a gourmet picnic dinner with wines to match. There was a bed-and-breakfast nearby where couples could spend the night.

“Perfect for our group,” Shell said.

Ann had been thrilled by the prospect of ballooning, and she accepted right away. She wasn’t sure how Jim would react. He had been moody around the house, sometimes snapping at Ann and the kids. He bought a ten-speed bicycle and started going on long rides on the weekends; sometimes he was gone for three hours. Ann thought the bike riding was probably a good thing. She said to Olivia, “He must have seen Breaking Away one night on TV. He’s obsessed with the biking.”

Ann started calling him “Cutter.”

She worried that Jim might not want to go on an all-day ballooning adventure with the wine-tasting group. But when she asked him, he said yes right away. It was almost as if he already knew about it, Ann thought.

It had been so many years earlier that certain details were now lost. What did Ann remember about the hot air ballooning trip? She remembered that Jim had been quiet in the car on the way to Asheville. Normally on a ride that long, he popped in a cassette of Waylon Jennings or the Marshall Tucker Band, and he and Ann sang along, happily out of key. But on that ride, Jim had been silent. Ann asked him what the matter was, and he said tersely, “Nothing is the matter.”

Jim liked to stop on the highway at Bob’s Big Boy for lunch. He positively adored Bob’s Big Boy; he always ordered the catfish sandwich and the strawberry pie. But this time, when Ann suggested stopping, he said, “Not hungry.”

Ann said, “Well, what if I’m hungry?”

Jim shook his head and kept on driving.

Ann remembered gathering with the group in the expansive green field; she remembered her heightened sense of anticipation. Along with Ann, Helen Oppenheimer seemed the most excited. She had been positively glowing.

Ann remembered the gas fire, the heat, the billowing balloon, the stomach-twisting elation of lifting up off the ground. She recalled the incredible beauty of the patchwork fields below them. The farmland, the woods, the creeks, streams, and ponds below them. She filled with pride. North Carolina was the most picturesque state in the nation-and she represented it.

The basket was eight feet square. Their group was packed in snugly. Ann, at one point, found herself hip to hip with Steve Fairlee and Robert Lewis as they leaned over the edge and waved to children playing a game of Wiffle ball below. It was only bad luck that caused Ann to turn around to see how Jim was faring. She happened to catch the smallest of gestures-Jim grabbing Helen’s hand and giving it a surreptitious squeeze. Ann blinked. She thought, What? She hoped she’d imagined it, but she knew that she hadn’t. She hoped it was innocent, but she knew Jim Graham. Jim wasn’t a hand grabber-or he hadn’t been-with anyone except for Ann. He used to grab Ann’s hand all the time: when they were dating, when they were engaged, the first few years of marriage. It was his gesture of affection; it was his love thing.

And at that moment, it all crashed down on Ann. The champagne party, the port party, Jim coming home at three in the morning, the absurdly long bike rides. He rode to Helen’s loft, Ann knew it, and they fucked away the afternoon.

Ann came very close to jumping out of the basket. She would die colliding with North Carolina; her body would leave an Ann-sized-and-shaped divot, like in a Wile E. Coyote cartoon.

Instead she turned. The fire was hot enough to scorch her. She called out, “Hey, Cutter!”

Jim and Helen both looked over at her. Guilty, she thought. They were guilty.

Once back on the ground, Ann drank the exceptional wine Shell had selected, but ate nothing. She tried to keep up with the conversation swirling around her, but she kept drifting away. Jim-and Helen Oppenheimer. Of course, it was so obvious. Ann had been so stupid.

She shanghaied Olivia, pulling her away from the picnic blankets to the edge of the woods. She said, “I think my husband is having an affair with Helen.”

Olivia gave her a look of sympathy. Olivia knew. Possibly everyone knew.

After the picnic was eaten and every bottle of wine consumed, they all piled into a van that drove them back to where their cars were parked. When they arrived, it was ten o’clock. The other couples were all making the short drive to the bed-and-breakfast for the night. Ann and Jim had booked a room at the B &B as well, but there was no way Ann was going to spend the night under the same roof as Helen Oppenheimer. She was certain Jim and Helen had made plans to meet in Helen’s room in the middle of the night to fuck.

When Jim and Ann got into the car, Ann said, “Jim.” His name sounded unfamiliar on her tongue; she had been calling him “Cutter” for weeks.

“Yes, darling?” Jim said. The wine had significantly lightened his mood, or seeing Helen had. Ann wanted to slap him.

Ann said, “You’re sleeping with Helen Oppenheimer.”

Jim froze with his hand on the key in the ignition. The other couples were pulling away. Helen, in the lipstick-red Miata she had bought herself upon leaving Nathaniel, was pulling away.

Jim said, “Annie…”

“Confirm or deny,” Ann said. “And tell me the truth, please.”

“Yes,” he said.

“Are you in love with her?” Ann asked.

“Yes,” he said. “I think I am.”

Ann nearly swallowed her tongue. Her head swam with wine and the fumes from the balloon.

“Drive home,” Ann said.

“Annie…”

“Home!” Ann said.

“She’s pregnant,” Jim said. “She’s pregnant with my child.”

Ann had started to weep, although the news didn’t come as a surprise. Ann had known just from looking at Helen that she was pregnant. The glow.

Jim drove the four hours home; they arrived in Durham at two in the morning. Ann took the babysitter home, and by the time she returned, Jim had a bag packed. The very next day he moved into Brightleaf Square with Helen, and when Chance was born, he bought a house in Cary. Ann was certain he did this so that he and Helen would no longer be Ann’s constituents.

It had not been Ann’s intention to relive all of this on the weekend of her son’s wedding. But since she’d made the ill-advised decision to invite Helen, it now seemed inevitable that this would be exactly what she was thinking about.

Ann knocked on the last door on the left, which was the room where Stuart was staying. “Sweetie?” she said. “It’s Mom.”

No response. She pressed her ear against the door, then tried the knob. It was unlocked, but she couldn’t bring herself to open the door. One of the things she had learned when the boys were teenagers was that she should never enter their rooms uninvited.

“Stuart, honey?” she said. “I made breakfast. There’s still some left, but you’d better hurry or H.W. will finish it.”

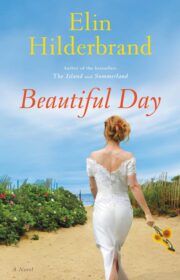

"Beautiful Day" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Beautiful Day". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Beautiful Day" друзьям в соцсетях.