“With a visit from Scotland Yard to our house in Kent. And while the police inspector was speaking to me, the new owners of our house came to claim it—it was the first time I’d learned that the house had been sold.”

She’d been stupefied by the shock of sudden eviction, the threat of an inquest, and, above all, the sheer vindictiveness of Tony’s action. Helena even believed that he’d deliberately committed suicide in the manner he had to provoke police interest, to make the ordeal as ugly as possible for Venetia.

“Why did he hate you so?”

She could detect no compassion in Christian’s voice—but no disdain either. “Because he believed that I’d turned him from somebody into a nobody. He’d married me to have a pretty accessory to garner himself more attention, but the pretty accessory stole all the limelight he craved and left him nothing.

“I know it makes no sense at all. I can scarcely credit it myself, a grown man resenting his wife for such a reason. But the notice I attracted maddened him—he wanted everyone’s gaze squarely on himself. To that end, he resolved be become an astoundingly successful investor, so that his friends and acquaintances would stop paying mind to the wife and look to him with envy and admiration. And while he was waiting for that to happen, he’d obtain adoration from other women.”

“Such as the maid he impregnated?”

“Poor Meg Munn. But maids were an unsatisfactory lot. He wanted his adulation to come from proper ladies, proper ladies who required such things as jewels before they’d admit a man to be impressive.”

A hint of a volatile emotion traversed his features, but a moment later his face was again unreadable.

“When his investments turned sour one by one, he kept me in the dark. I didn’t know he’d become mired in debts. I only knew the amount I was allocated to run the household kept decreasing—and I thought that was because he was mean-spirited.”

Not a pretty confession, only a truthful one. “He must have believed that he’d strike gold on one of his investments. They all failed. It would have been terrifying for anyone, but for him … the implication that he had not been favored by God, that he could fall from grace just like any other ordinary bloke, and that he could do to nothing to stop this plunge into poverty and obscurity—he must have been in hell already.”

She’d never given a full recital of the facts. Perhaps she should have years ago. Then she’d have realized much sooner that the person Tony had condemned from the beginning was himself.

And only himself.

She sighed, whether from sorrow or relief Christian couldn’t quite tell. What he did know was that he wished Townsend were still alive so he could bash in the man’s face and break a few of his ribs besides.

She twirled the end of her robe’s sash between her fingers, waiting for him to say something—or perhaps simply waiting for him to leave so she could go back to her fossils. As his gaze remained upon her, she cinched the sash rather self-consciously.

The shape of her body hadn’t changed. The tightened sash attested to a waist just as slender as it had been on the Rhodesia. He would not have guessed that she carried a new life within.

He hadn’t been in the nursery in a while. There might still be some of his toys and books in there. And, of course, the whole of the estate was one vast playground for a child. “When will the baby be born?”

Her eyes turned wary. “Beginning of next year.”

He nodded.

“I wouldn’t be in such a hurry to speak to your lawyers if I were you.”

He hadn’t been thinking of speaking to his lawyers at all. “No?”

“Even they would think you a monster were you to orchestrate a divorce right after my confinement.”

“How long do you recommend I wait, then?”

“A long time. I know what happens when a divorce is granted: The woman never gets anything. And I will not be parted from my child.”

“So you will contest the divorce?”

“To my last penny. And then I’ll borrow from Fitz and Millie.”

“So we’ll be married ’til the end of time?”

“The sooner you accept it, the sooner we are all better off.” His ancestors would have appreciated her hauteur: a fit wife for a de Montfort. “Now if you’ll excuse me, I must have enough rest.”

He gazed at her retreating back. Foolish woman, did she not realize that he’d already accepted it from the moment he’d said “I do”?

CHAPTER 18

Christian had a fitful night—not that he’d known any other kind since she’d disembarked the Rhodesia. But after their encounter in his private museum he could only reel with shame and horror at how wrong he had been. What must she have felt, to have her character twisted and denigrated so carelessly, without the slightest regard for the truth.

In the morning he stopped by the breakfast parlor. He’d been having breakfast in his study, but he knew she usually had hers in the parlor, with the day’s papers and often a copy of Nature by her elbow.

She was not there.

“She has gone for a walk, sir,” said Richards.

“Where?” The grounds of Algernon House were vast. She could be miles away.

“She did not inform us, sir. She only said not to expect her before luncheon.”

“When did she leave?”

“About two hours ago, sir.”

It was not quite nine o’clock yet. If she did not come back before luncheon, she’d be out a good six hours. “You let a woman in her—”

Christian stopped himself. No one else knew of her condition yet. “Send me Gerald. Tell him to hurry.”

Gerald, head groundskeeper, arrived slightly out of breath. “Your Grace?”

“Has the duchess asked you any questions about the quarry?”

“Yes, sir, she has indeed.”

“When?”

“Yesterday, sir.”

“Did she ask for directions?”

“She did, sir. I drew her a map. She also asked about digging implements and I told her about the cabin with all the tools in it.”

“Isn’t the cabin locked?”

“She asked for my key, sir, and I gave it.”

Ten minutes later, Christian was on his horse, galloping toward the quarry.

The remains of the quarry consisted of a near-circular cliff with a ramp going down to the bottom. To reach the top of the ramp, he had to guide his stallion up a small hill. The sight that greeted him as he crested the knoll made him lose his breath.

Standing halfway up the earthen ramp that he’d had built years ago to facilitate access to the higher parts of the cliff was his baroness, complete with the veiled hat that had been such a part of her mystery. She stood with her back to him, studiously chipping away at a promising patch of sediment, late Triassic by the look of it. Setting down her hammer and chisel, she picked up a brush and swept away the debris around an ocher-colored protuberance. All the while she whistled, a lively aria from Rigoletto, her notes bright and exactly in tune, until she hit a sustained high note where she ran out of air and stuttered. This made her giggle.

At the sound of her laughter, the Ghost of Ocean Crossings Past shouldered through him, a great, muscular longing.

He did something: tightened his hands on the reins or the grip of his thighs on the flanks of his steed. The horse shifted, struck its hooves against the ground, and let out a rumbly neigh.

She looked over her shoulder. The front of the veil had been lifted over the crown of her hat; her face was dirty and smudged, her extraordinary eyes largely hidden beneath the wide brim. All the same he felt the familiar upending of his peace of mind, of the ingrained expectation that he should affect the world and those in it, but not the other way around.

He nudged his mount forward. At the bottom of the slope there was a hitching post. He tied the horse and made his way up the ramp.

“How did you find me?”

“It’s not that difficult to guess which part of my estate you may wish to explore. What have you found?”

She glanced at him, seemingly surprised by his civility. “A very small skull. I am hoping it might be a juvenile dinosaur but most probably not—it’s too far into the Tertiary strata.”

“An amphibian, by the looks of it,” he judged.

She did not quite look at him. “I’m still thrilled.”

A silence spread. He didn’t know what to say. For a man of science, a devotee to cold facts, he had blundered badly, allowing his action to be guided by assumption after ill-supported assumption. “You said you were there at my Harvard lecture in person,” he heard himself say. “Why didn’t you approach me afterward and correct my misconceptions?”

She swirled the bristles of a brush against the skull’s small, sharp teeth. “I couldn’t have shared the most painful details of my life with a stranger who had coldly condemned me.”

No, of course not.

“So you chose to punish me instead.”

She drew a deep breath. “So I chose to punish you instead.”

His hand tightened around his riding crop. For a moment it seemed that he was about to say something, but he only inclined his head and left: untethered his horse, rode it up the slope, and disappeared from sight.

Venetia bit her lower lip. She was still unsettled from their conversation the night before, during which she had shared the most painful details of her life, and he had reacted not at all.

But then he too had shared his most closely held secret and she had thrown it back in his face—with great glee, as far as he could tell.

She sat down to rest on a hardened clump of soil. After a while, she thought of picking up the hammer and the chisel and chipping away some more at the edges of the skeleton. But her arms were sore and each whack of the hammer had jarred the socket of her arm. It had been a long time since she last dug: Then she’d been an indefatigable child who never ached anywhere; now she was a pregnant woman who didn’t sleep well.

It would be wiser to be on her way back to the house. She had prepared for her outing with a flask of tea and a sandwich. The sandwich was already gone—eaten en route, as it had taken her longer than expected to find the site. The flask, too, was nearly empty—the day had warmed fast.

It would be a hot, thirsty walk home.

The sound of horse hooves and wheels. She spun around, hoping to see Christian. But it was only Wells, the gamekeeper, who’d come in a two-wheel dogcart pulled by a Clydesdale.

“Do you need a lift to the manor, mum?” said Wells.

Venetia was surprised and relieved. “Yes, I do. Thank you.”

Wells carried the bucket of tools back to the shed while she climbed up to the slope to the dogcart.

“Did you happen by the quarry?” she asked, once he had helped her up to the high seat. The gamekeeper’s cottage was somewhere nearby, from what Gerald had told her.

“No, mum. His Grace stopped by and asked me to wait on you. He also asked the wife to have some tea and some biscuits for you.”

Wells passed her a basket covered with a large napkin. She ate a biscuit. It tasted lemony. “It’s very kind of you and Mrs. Wells.”

And even kinder of Christian, to arrange for transport and nourishment, before she’d even realized her needs.

All of a sudden she couldn’t wait to see him again. Enough of the Great Beauty. Enough of her pride. And enough of this fretting about their impasse. He was the love of her life—it was time she treated him as such.

“Would you mind hurrying a little?” she asked Wells, who drove as if the dogcart were the state carriage during the Queen’s Jubilee.

“His Grace said I was to drive slow and steady, so as to not jostle you, mum.”

“That’s very lovely of His Grace, but I’m not afraid of jostling. Faster, please.”

The Clydesdale went from a stately trot to a more energetic trot, but Wells refused to accelerate further. Venetia waited impatiently for the manor to come into view. And when the dogcart drew up before the front steps, she thanked Wells and ran inside.

“Where is the duke?” she asked the first person she came across, who happened to be Richards.

Richards looked surprised at the question. “His Grace has departed for London.”

Christian hadn’t said a thing about leaving Algernon House. “Of course,” she murmured, hoping she didn’t look as she felt, faltering. “I meant when did he leave?”

“Half an hour ago, ma’am.”

“Thank you, Richards,” she said numbly.

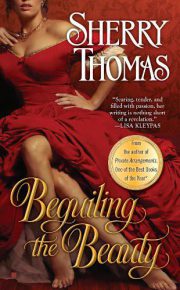

"Beguiling the Beauty" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Beguiling the Beauty". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Beguiling the Beauty" друзьям в соцсетях.