He was pleased with himself—too much so, perhaps. To a naturalist, there was no act more mundane than the sexual one. Yet making love to Baroness von Seidlitz-Hardenberg had been anything but ordinary. To the contrary, it had felt momentous, far more significant than merely the beginning of a weeklong affair.

He’d been so caught up in the heady events of the evening he hadn’t even given a thought to a sponge or a French letter until now, he who was usually far more scrupulous about such things. That she was in his bed was another aberration. In his liaisons, he preferred to set the itinerary, to leave or stay as he chose. But this time, he’d ceded the control to her: She wanted to conquer her fear, and that appealed to his sense of gallantry.

He lifted a strand of her hair and wound it about his fingers. “I’m glad you decided to reconsider my proposition.”

Against his shoulder, she made a sound, something of a humfft.

He let go of her hair, turned her face, and kissed her on her mouth. “What made you change your mind?”

Her answer was the same humfft, but she tensed again—he felt it in the set of her jaw.

He had an idea why she might not be keen on speaking to him: She probably thought he’d propositioned her randomly and she still hadn’t made peace with her eventual acceptance.

“There is an interesting contradiction to you. You hide your face, but your gait is anything but retiring.”

Not only did he want her to stay, tonight he’d be the one to make conversation as well—quite a reversal for a man who was more accustomed to seeking his solitude afterward.

“Oh?” she murmured against his cheek.

“You walk with a certain swagger. Not a strut, mind you, but a confident, assertive gait. A woman out and about with her face covered can expect a great deal of attention, which can be daunting. But you carry on as if this attention is the least of your concerns, as if you daily part a sea of staring eyes.”

She stirred. “And that interests you?”

“Your reasons interest me. I asked myself whether you might be a fugitive, and decided no, the veil makes you far too visible. There is also a small chance you are a Musulman, but no Musulman woman who takes the trouble to cover her face entirely would be caught dead traveling unaccompanied. Which leaves two possibilities. One, you simply do not wish to show anyone your face, and two, there is something highly irregular about your features.”

She pulled away. “You’ve a taste for deformed women, sir? Is that why you asked me to be your lover?”

“Did I ever ask you to be my lover?”

“Of course you—” She stopped.

When he’d stated that he’d like to know her better, she’d been the one to ask whether he was looking for a lover.

“When you instantly jumped to the conclusion that I’d like to sleep with you, you answered my question. A woman of highly irregular features might be suspicious about my interest in her, but she is unlikely to immediately accuse me of a lascivious overture. You, on the other hand, take it for granted that a man’s interest in you lies in that direction.

“Since there is nothing physically wrong with you, if I were to pretend I did not have some carnal curiosity about you, I’d be lying. So, yes, I acknowledged that component of my intent. But if you’d asked, I’d have told you that I was more interested in the why of you than the naked pleasures of your body.” It was strangely easy to talk to this faceless woman in the dark, as if he were speaking to the sea or the sky. He brushed her hair back from her shoulder. “Although, had I known just how monumental were the naked pleasures you’d bring into the bargain, I’d have pursued you with much greater vigor.”

He must have failed abysmally at explaining himself—or offended her anew. For she pushed away from him and sat up.

“I should go.”

Would you like me to help you find your clothes? They might be scattered around—I’m afraid I wasn’t too careful about collecting them in a neat pile.”

His German was quite nimble and there was a smile in his voice. She bit her lower lip. Why hadn’t she planned things better? How would she be able to find everything in the dark—and dress herself to a semblance of decency?

He left the bed the same time she did. “This is something of yours. This is mine. What is this? A corset cover?”

Her toes encountered her shoes and stockings. But before she could pick them up, he was already upon her, handing her a bundle of clothes. When she took the clothes from him, his hand brushed her arm.

“Need some help dressing?”

“No, I—”

“We’ll pretend this is an excavation site and work methodically,” he said, taking the clothes from her again. “I’ll lay out your clothes on the bed one by one, then we’ll know what is what and which pieces are still missing.”

She had not expected this helpful alacrity. Her clothes landed on the bed with a small whomp. He rounded to the other side of the bed, presumably to begin the classification of said garments.

She bent down and gathered her stockings. When she straightened, she came up against what felt like a very soft blanket at her back. “Put it on, or you’ll be cold,” said Lexington.

It was a dressing gown of merino wool. She tightened the sash at her waist. “What about you?”

“I have found my trousers. Now, let’s see about your clothes. Your dress”—something rustled; his voice once again came from the far side of the bed—“will form the bottom of the heap, to be followed by everything else in reverse order. How many petticoats were you wearing?”

“One.”

“Only one?”

“The skirt is split, so the dress comes with an embroidered inner skirt. And the cut is narrow. More than one petticoat and the fit will suffer.”

Why had she explained in such detail? It was almost as if she was afraid he’d think the lack of multiple petticoats translated into moral laxity on her part. When she’d just slept with a man to whom she hadn’t even been properly introduced!

“Wise choice,” he murmured. Again that smile in his voice. “The fit most certainly did not suffer.”

She felt as if she’d fallen down the rabbit hole. Or perhaps he was a strange incarnation of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde—but instead of turning evil in the dark, he became much nicer.

“Can you find your way here?” he asked. “I have your things in readiness.”

She skirted the edge of the bed. “Where are you? I don’t want to step on your foot.”

“Hmm,” he said, “there is an accent to your German.”

She halted. She’d grown up with a German governess. Native German speakers usually remarked on her lack of an English accent. “What kind of an accent?”

“I’ve spent some time in Berlin and you don’t have the vowels of Prussia proper, either the German parts or the Polish parts. You sound as if your origins are farther south—Bavaria, I’d say.”

Her German governess had indeed been from Munich and spoke the lilting Bairisch dialect. “Very good for an Englishman.”

“Yet I’m not convinced you are German.”

Too good for an Englishman. “Why not? You yourself identified my Bavarian accent.”

“When I mentioned your accent, you stopped cold. You are still standing in place, by the way.”

She remained where she was. “Does it matter whether I am German, Hungarian, or Polish?”

“No, I suppose it doesn’t. Is your name really von Seidlitz-Hardenberg?”

“And what if I am not a baroness, either? Will that cause the Rhodesia to sink?”

“No, but I’m convinced it precipitated the storm.”

Judging by his tone, he was smiling once more—and standing all too close.

His hand combed her hair. “What are you still afraid of?”

“I’m not afraid of anything.” Yet she sounded as if she were cowering.

“Good, you shouldn’t be. What can I do to you? Once we disembark, I wouldn’t know you even if we came face-to-face.”

But she’d planned differently, hadn’t she? At Southampton, she meant to reveal herself and let him know he’d been had. She’d imagined this denouement in dozens of delicious variations, each leading to that inevitable point of rage and devastation on his part. Looking back, it was as if she’d planned a trip to the moon, with her only qualification an enthusiasm for Monsieur Verne’s scientific romances.

He tucked back her hair and kissed her beneath her earlobe, the sensation so jagged it almost hurt. Nibbling a path down the column of her neck, he pushed aside the collar of her dressing gown and exposed her shoulder.

“You are so very tense again, my dear baroness who may or may not be a baroness.”

“You make me feel nervous.” And guilty, even though she’d yet to do anything more reprehensible than sleeping with a man she did not love—or like.

He lifted her and set her down at the edge of the bed. “Unforgivable on my part. Let me offer my recompenses.”

He undid the sash on her dressing gown. She fought a renewed surge of panic. “Why are you nice to me?”

“I like you. I’m never unpleasant to people I like.”

“You are a high-minded man, are you not?”

“I do have some exacting standards.”

“As a man of exacting standards, can you justify to yourself why you like me, beyond that I am a source of naked pleasures?”

“You turned me down, and that speaks well of you—a man who went about it with as little finesse and forethought as I did deserved to be rebuffed. Other than that, you are right; I don’t have any firm foundations for approving of you. All the same, when you changed your mind, I was terribly flattered. So I am going to be unscientific and call this simply an affinity.”

Affinity. When in real life, he had the greatest antipathy for her.

“There is something else about you that I like,” he continued. She didn’t know when he’d pressed her into bed, but she lay with him beside her, her dressing gown completely open. Lightly he ran his hand over her breasts and her abdomen. “I like that I can make you forget, however briefly, everything that agitates you.”

He made love to her again. Afterward, when she began to deliberately bring her breathing under control, Christian knew that she’d left her sweet oblivion behind. This time, when she told him that she must go, he pulled on his trousers and helped her dress. Then he went out to the parlor and brought back her hat.

“What about your hair?” He’d discarded the pins and combs that had held together her coiffure. “I’ve scant knowledge on the repair of ladies’ hair.”

“I’ve the veil,” she said. “I’ll manage.”

Once her face was safely obscured behind the veil, he turned on the lamps and shrugged into his shirt.

“It’s late. I’ll walk you back.”

The light danced upon the warp and woof of her veil, which rippled just perceptibly as she exhaled. He had the feeling she was about to turn down his offer, but she said, “All right, thank you.”

A sensible woman, for he’d have insisted.

He remained in the bedroom. She walked slowly about the parlor, taking in the coffered ceiling, the stack of books on the writing desk, and the vase of red and yellow tulips on the mantel. For some reason he’d thought her dinner gown cream-colored, but it was apricot, the skirt spangled with beads and crystal drops.

He snapped his braces over his shoulders and tossed on a waistcoat and an evening coat. His cuff links, emblazoned with the Lexington coat of arms, were on the floor. He bent down and retrieved them.

As he straightened, he felt pinpricks upon his skin—the weight of her gaze. He glanced at her. She looked away immediately, even though he could see nothing but her faintly glimmering veil.

She did not trust him—or like him entirely, for that matter. And yet she’d let him seduce her—or was it the other way around?—twice. He could flatter himself and attribute the discrepancy to an intense attraction on her part, but years of training in objectivity made such delusions impossible.

He put on the cuff links. He even went to the trouble of a fresh necktie. If they were seen together at this hour, it might lead to certain suspicions, but he was not about to give concrete evidence by looking disheveled.

“Shall we?” He offered his arm.

She hesitated before laying her hand on his elbow. Still jittery, his baroness, almost as much as she’d been when she’d arrived in his suite. But questions to that regard set her on edge, so he refrained.

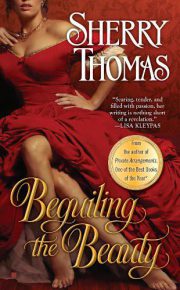

"Beguiling the Beauty" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Beguiling the Beauty". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Beguiling the Beauty" друзьям в соцсетях.