They skirted around a bank of standing bookshelves in the middle of the room and came face-to-face with the head of a dragon—or the neck and head of one, to be exact. Openmouthed and baring sharp teeth, the wooden carving was about her height, on display in a glass case.

“That’s Drake,” Winter said, stuffing his hands in his pockets. “The bow off a Viking longship from the twelfth century.”

“You are Scandinavian, then?”

“Swedish. My parents immigrated here when my mother was pregnant with me.”

“An arduous journey for a pregnant woman.”

Something in his brow shifted. A wistfulness. Or guilt, perhaps. “She insisted on coming to give me a better life. My siblings were born here.”

She walked around the dragon, peering through the glass. The carving was crude, the wood cracked and splintered. “Shouldn’t this be in a museum?”

“Probably. If we ever need money, we can sell him. He’s worth more than the whole damn house. It was one of the first things my father had imported after the bootlegging money started flowing. I’ve got an uncle who’s an archaeologist. My younger brother is on a dig with him out in Cairo right now.”

“Really? How exciting. Hope he’s not opening up any cursed tombs.”

“My brother could fall into shit and come out smelling of roses.”

Aida laughed.

In a fluid pair of movements, Winter curved his body closer to hers while settling his forearm above his head on the top of the glass case. His fingers tapped on the glass. A big body like his possessed an unspoken dominance if the personality commanding it understood its power, and Winter did. He towered over her at an angle that forced her to tilt her face up and back to meet his gaze, and spoke in a lower, more relaxed tone, as if he were sharing a choice bit of gossip, luring her into his web. “Uncle Jakob found the dragon bow a few years ago. Found three, actually—reported one, kept one for himself, and gave my father Drake, here.”

“Lawbreaking runs in the family.”

He made a grunting noise. “My uncle is fond of shipping black market goods, and my father always had boats. That’s why he got into bootlegging in the first place.”

“Bo mentioned that your father was a fisherman.”

“Crab and salmon, mainly. I’ve traded most of the fishing fleet for rumrunners and a couple of big, new powerboats that go to Canada. But I haven’t gotten rid of the crabbers.”

“You still crab?”

“It’s good money and a legitimate cover for the booze.”

She glanced at a long bay of windows lining the outer wall of the study and left Winter to survey the view. “Oh, look at that. Bet you can see the entire city when it’s clear.”

Winter’s low voice was closer than she expected. He pointed over her shoulder. “You can see Fisherman’s Wharf and Alcatraz Island from here. If the bay wasn’t foggy, we could also see the northern point of the Presidio where they’re going to build a suspension bridge across the Golden Gate strait to Marin County. Have you heard about it?”

“No.”

“Will be the longest in the world, if they ever raise the funds to build the damn thing.”

“Impressive.”

They gazed out over the rooftops for a moment until Winter spoke again. “Velma said you’re booked at Gris-Gris through July. What do you do, just go from club to club?”

“Sometimes theaters, but speakeasies pay better. I’ve worked six of them over the past couple of years up and down the East Coast. This is the first time I’ve been out West since I was a small child. I’m originally from here—my parents were killed in the Great Fire.”

“I’m sorry.”

“I was only seven, so my memories are limited. Our apartment building initially survived the quake. It was one of the gas pipe explosions that brought it down. I got separated from my parents when we were trying to escape. One of the neighbors got me out, but my parents never made it. To this day, I’m a little phobic of fire.”

“Understandable. I was nine when it happened, but I still dream about the city burning.”

God, so did she.

“What happened to you after the fire?” Winter asked.

“I was shuffled off to a temporary camp, then an orphanage. I lived with three families before a couple, the Lanes, took me in later that year. They were moving out east, so I went with them.” She glanced out the window. “I have a few memories of living here before the quake, but I definitely don’t remember it looking like this. It’s going to spoil me. I won’t want to leave.”

“How do you live like that, moving around all the time? Do you travel with someone?”

“Just me and myself.”

Two deep lines etched his brow. “Doesn’t seem safe for a single woman to be running around the country.”

If she had a penny for every time she’d heard that . . . “I’ve managed just fine.”

“Sounds lonely.”

It was lonely at times—terribly lonely. But she did what she had to in order to survive, and she wasn’t embarrassed about it. A certain pride came with the kind of independence she had. If you didn’t rely on anyone but yourself, you had fewer chances of being disappointed—that’s what Sam always told her. Out of habit, her fingers reached for the locket hanging near her heart.

“I live for the moment, not the past or future,” she said. Another Sam mantra. “But if you must know, I do prefer private séances to work onstage. They pay better for less work. Building up a client list takes more time than—”

A loud brring-brring startled her out of her memories.

“Hold that thought.” Winter excused himself and strode across the room to answer the telephone. She was a little relieved to drop the subject of her career choice. It was none of his business, really. And she’d already said more than she probably should. A bad habit of hers, not controlling the things that exited her mouth.

While he spoke in a hushed voice on the phone, she strolled past the windows and looked around, glancing at the book spines on a bay of shelves, mostly commerce and fishing titles. Her gaze fell upon a couple of long books sitting on a nearby lamp table. Scrapbooks? Photos?

Leather cracked when she opened the top book. Not photographs, but postcards attached to black pages with adhesive mounting corners. Postcards from Cairo. Postcards from France. The Eiffel Tower. The Arc de Triomphe. The Louvre. Two French maids wearing nothing but aprons. A girl falling off a bike, her skirt lifted, wearing only rolled-down stockings underneath. A woman sitting on a sofa reading a French copy of Ulysses with her legs spread—

Dear Lord.

Erotic postcards. Dozens and dozens. She glanced in Winter’s direction. He was quiet, listening to the earpiece receiver while pacing around the fireplace, toting the candlestick base as a black telephone cord snaked around the floor, trailing his footsteps.

She hurriedly leafed through the pages, which seemed to get progressively worse—or better, depending on your view. A fully dressed man kissing a nude woman on his lap. A man fondling a woman beneath her chemise.

Flipping toward the back of the book, Aida stopped on a page with only one postcard affixed to the center—not a photograph, but a colored illustration. It featured a naked woman with bobbed hair. She sat upon the lap of a naked man, who was propped up against a pile of cushions. His cock was drawn to fantastical proportions, and the artist had managed to include an impressive amount of detail in rendering every vein, ridge, and hair as it slid into the woman’s exposed sex. She rode him, mouth open, with a look of ecstasy on her face.

And she was freckled.

Aida’s pulse pounded. She stared at the shocking postcard, transfixed. It was surely only a coincidence the illustrated woman looked like her—artists often added freckles to make females look younger, after all, and—

“Find something interesting?” Winter’s low voice rumbled near her ear.

She jumped in surprise and attempted to shut the book, but his palm slapped down on the pages. When she tried to step away, another hand planted on the other side of the book, pinning her inside his arms. His chest against her back was warm and solid.

Her breathing faltered. Embarrassment created a fog that rolled over her brain. “They were sitting out,” she argued dumbly.

“My study. My books. I can leave them where I like.”

Her heart pattered like a frightened animal. “You should take more care when you invite guests over.”

“I didn’t know my guest would be so curious.”

“And I didn’t know I’d be visiting a deviant!”

“One man’s deviance is another man’s lunch break.”

“Pervert.”

His mouth was against her ear, his words spoken through her hair. “Are you referring to me or yourself? You’ve been staring at that for quite a long time.”

Her face flamed. She never blushed. Never! “It’s . . . depraved.”

“How so?” His thumb ran along the edge of the postcard. “Is the artist depraved for rendering a fantasy, or is the woman in the painting depraved for enjoying it?”

“You’re the one who’s depraved for owning it.” She shoved her shoulders back against him, grunting. “Let go.”

He didn’t grip her tighter, nor impede her from ducking out of his hold, but instead distracted her with words. “Look closer,” he said, pointing to the woman in the illustration. “There’s a trust between them. She enjoys him watching her. Oh, and would you look at that? She’s got freckles just like you. How interesting.”

Aida’s eyes flicked to the bulky arms flanking her shoulders. She twisted inside his trap, defiantly faced him, and shoved at his chest. A useless act against someone built like a mountain; he didn’t budge.

She drew back. He leaned forward, erasing the distance. Their combined weight pressing against the lamp table caused it to slide a few centimeters. A frightening, almost unbearable intensity darkened his eyes. She could no longer tell which pupil was bigger, because both were enlarged beneath languid, drooping eyelids.

“Do you like people watching you onstage, Aida?”

The question was, at best, rude, and paired with the postcard, the insinuation behind it was downright vulgar. But it was her name on his lips that unexpectedly triggered lust to uncoil low in her belly. It sounded so startlingly intimate, and he was so close. So close, so big . . . so intimidating. She was overawed and overexcited, all at once.

His gaze dropped. Hers followed, only to find the hands that had shoved at his chest were now grasping his necktie, either in an attempt to choke him or pull him closer.

Maybe both.

“Christ alive,” he whispered thickly.

Her thoughts exactly—what on earth did she think she was doing? Rattled by her own lack of restraint, she released the necktie and ducked under his arm, then took several quick steps to put some distance between them.

“Sorry,” she mumbled with her back to him. “I’m not sure what came over me.”

He didn’t answer. God, she’d rattled him. Probably a first. And now that her foggy brain was clearing, she was uncertain about his intentions. Do you like people watching you onstage, Aida? Maybe she’d misread this completely. Perhaps he’d only been trying to intimidate her after she’d rudely plowed through his personal things, and she’d only been hoping he didn’t mind the freckles. Maybe she’d just been fooling herself because she wanted him to want her as much as she wanted him.

But wants and needs aren’t interchangeable, and what she needed right now was to cool down and gather her wits. She exhaled heavily, and the breath that rushed out of her mouth was a chilly white cloud.

SIX

IT TOOK SEVERAL MOMENTS FOR WINTER TO COMPOSE HIMSELF enough to turn around. He was uncomfortably hard, aching and straining against the front of his pants. The fact that she provoked such an immediate response in him wasn’t a surprise—he had, after all, spent the last few nights conjuring images of her while he stroked himself to sleep. Thank God she hadn’t flipped one more page in his postcard collection, or she’d have seen the program he’d taken from Gris-Gris, folded inside out with her photograph bared.

But really, could he be blamed for that? She was beautiful, vivacious, and carefree. Of course he wanted her. It was her response that had him thrown for a loop. Because unless the blood now pulsing inside his cock had emptied his brain and made him daft, he suspected she wanted him, too. How was that possible?

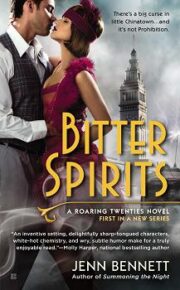

"Bitter Spirits" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Bitter Spirits". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Bitter Spirits" друзьям в соцсетях.