He grinned appreciatively, but said: “You may be right, but you can’t expect me to agree with you. After all, I tried to marry Celia myself!”

“Yes, but you were only a boy then. You must be wiser now!”

“Much! Too wise to meddle in what doesn’t concern me!”

“Mr Calverleigh, it should concern you!”

“Miss Wendover, it don’t!”

“Then, if you’ve no interest in your nephew, why do you mean to linger in Bath? Why do you hope he means to return here?”

“I didn’t say I had no interest in him. I own, I didn’t think I had, but that was before I knew he was making up to your niece. You can’t deny that that provides a very interesting situation!”

“Excessively diverting, too!”

“Yes, that’s what I think.”

She said despairingly: “ I see that I might as well address myself to a gate-post!”

“What very odd things you seem to talk to!” he remarked. “Do you find gate-posts less responsive than eels?”

She could not help smiling, but she said very earnestly: “Promise me one thing at least, sir! Even though you won’t intervene in this miserable affair, promise me that you won’t promote it!”

“Oh, readily! I am a mere spectator.”

She was obliged to be satisfied, but said in somewhat minatory accents: “I trust your word, sir.”

“You may safely do so. I shan’t feel any temptation to break it,” he replied cheerfully.

Feeling that this remark showed him to be quite irreclaimable, Abby walked on in silence, trying to discover why she allowed herself to talk to him at all, far less to accept his escort. No satisfactory answer presented itself, for although he seemed to be impervious to snubs she knew that she could have snubbed his advances if she had made any real effort to do so. After a half-hearted attempt to convince herself that she endured his escort and his conversation with the sole object of winning his support in her crusade against his nephew she found herself to be under the shameful necessity of admitting that she enjoyed both, and—far worse!—would have suffered considerable .disappointment had he announced his intention of leaving Bath within the immediate future. She could only suppose that it was his unlikeness to the other gentlemen of her acquaintance which appealed to her sense of humour, and made it possible for her to tolerate him, for there was really nothing else to render him acceptable: he was neither handsome nor elegant; his manners were careless; and his morals non-existent. He was, in fact, precisely the sort of ramshackle person to whom no lady of birth, breeding, and propriety would extend the smallest encouragement. He had nothing to recommend him but his smile, and she was surely too old, and had too much commonsense, to be beguiled by a smile, however attractive it might be. But just as she reached this decision he spoke, and she glanced up at him, and realized that she had overestimated both her age and her commonsense. He was smiling down at her, and, try as she would, she was incapable of resisting the impulse to smile back at him. It was almost as if a bond existed between them, which was tightened by his smile. In repose his face was harsh, but the smile transformed it. His eyes lost their cold, rather cynical expression, warming to laughter, and holding, besides amusement, an indefinable look of understanding. He might mock, but not unkindly; and when he discomfited her his smiling eyes conveyed sympathy as well as amusement, and clearly invited her to share his amusement. And, thought Abby, the dreadful thing was that she did share it. He seemed to think that they were kindred spirits, and the shocking suspicion that he was right made her look resolutely ahead, saying: “Yes, sir? What did you say?”

Quick to hear the repressive note in her voice, he replied meekly: “Nothing, I assure you, to which you could take the least exception! In fact, no more than: I wish you will tell me. Upon which you turned your head, and looked up at me so charmingly that the rest went out of my mind! How the devil have you contrived to escape matrimony in all the unnumbered years of your life?”

An unruly dimple peeped, but she answered primly: “I am very well content to remain single, sir.” It then occurred to her that this might lead him to suppose that her hand had never been sought in matrimony, which, for some reason unknown to herself, was an intolerable misapprehension, and she destroyed whatever quelling effect her dignified reply might have had upon him, by adding: “Though you needn’t suppose that I have not received several eligible offers!”

He chuckled. “I don’t!”

Blushing rosily, she said, trying to recover her lost dignity: “And if that is what you wished me to tell you—”

“Oh, no!” he interrupted. “Until you smiled so enchantingly I thought I knew. But you aren’t old cattish—not in the least!”

“Oh!” gasped Abby. “Old cattish? Oh, you—you—I am nothing of the sort!”

“That’s what I said,” he pointed out.

“You didn’t! You—you said—” Her sense of the ridiculous came to her rescue; she burst out laughing. “Odious creature! Now, do, pray, stop roasting me! What do you really wish me to tell you?”

“Oh, I was merely seeking information! I don’t recall that I ever visited Bath in the days of my youth, so I rely on you to tell me just what are its rules and etiquette—as they concern one desirous of entering society.”

“You?” she exclaimed, casting a surprised look up at him.

“But of course! How else could I hope to pursue my acquaintance with—” He paused, encountering a dangerous gleam in her eyes, and continued smoothly: “Lady Weaverham, and her amiable daughter!”

She bit her lip. “No, indeed! How shatterbrained I am! Lady Weaverham has several amiable daughters, too.”

“Good God! Are they all fubsy-faced?”

“A—a little!” she acknowledged. “You will be able to judge for yourself, if you mean to attend the balls at the New Assembly Rooms. I am afraid there are no balls or concerts held at the Lower Rooms until November. You will find it an agreeable day promenade, however, and I expect there will be some public lectures given there. Concerts are given every Wednesday evening at the New Rooms. And there is also the Harmonic Society,” she said, warming to her task. “They sing catches and glees, and meet at the White Hart. At least, they do during the season, but I am not perfectly sure—”

“I shall make it my business to discover the date of the first meeting. Meanwhile, my pretty rogue, that will do!”

Miss Wendover toyed for a moment with the idea of giving him a sharp set-down for addressing her so improperly, but decided that it would be wiser to ignore his impertinence. She said: “Not fond of music, sir? Oh, well, perhaps you have a taste for cards! There are two card-rooms at the New Assembly Rooms: one of them is an octagon, and generally much admired—but I ought to warn you that hazard is not allowed, or any unlawful game. And you cannot play cards at all on Sundays.”

“You dismay me! What, by the way, are the unlawful games you speak of?”

“I don’t know,” she said frankly, “but that’s what it says in the Rules. I expect it wouldn’t do to start a faro bank, or anything of that nature.”

“I shouldn’t wonder at it if you were right,” he agreed, with the utmost gravity. “And how do I gain admittance to this establishment?”

“Oh, you write your name in Mr King’s book, if you wish to become a subscriber! He is the M.C., and the book is kept at the Pump Room. Dress balls are on Monday, card assemblies on Tuesday, and Fancy balls on Thursday. The balls begin soon after seven o’clock, and end punctually at eleven. Only country dances are permitted at the Dress balls, but there are in general two cotillions danced at the Fancy balls. Oh, and you pay sixpence for Tea, on admission!”

“And they say Bath is a slow place! You appear to be gay to dissipation. What happens, by the way, if eleven o’clock strikes in the middle of one of your country dances?”

She laughed. “The music stops! That’s in the Rules too!”

They had reached Sydney Place by this time, and she stopped outside her house, and held out her hand. “This is where I live, so I will say goodbye to you, Mr Calverleigh. I am much obliged to you for escorting me home, and trust you will enjoy your sojourn in Bath.”

“Yes, if only I am not knocked-up by all the frisks and jollifications you’ve described to me,” he said, taking her hand, and retaining it for a moment in a strong clasp. He smiled down at her. “I won’t say goodbye to you, but au revoir, Miss Wendover!”

She had been afraid that he would insist on entering the house with her to make Selina’s acquaintance, and was relieved when he made no such attempt, merely waiting until Mitton opened the door, and then striding away, with no more than a wave of his hand.

She found, on going upstairs, that Selina had promoted herself to the sofa in the drawing-room, and had had the gratification of receiving a visit from Mrs Leavening. She was so full of Bedfordshire gossip that it was some time before Abby had the opportunity to tell her that Mrs Grayshott’s son had at last been restored to her. She found it unaccountably difficult to disclose that Mr Miles Calverleigh had brought him to Bath, and when, after responding to her sister’s exclamatory enquiries, she did disclose it, her voice was a trifle too airy.

Selina, fortunately, was too much surprised to notice it. She ejaculated: “ What? Poor Mr Calverleigh’s uncle? The one you told me about? The one that was sent away in disgrace? You don’t mean it! But why did he bring the young man home? I should have thought Mr Balking would have done so!”

“I believe he took care of him on the voyage.”

“Good gracious! Well, he can’t be so very bad after all! and very likely Mr Stacy Calverleigh isn’t either! Unless, of course, he only came to find his nephew—not that there is anything bad about that: in fact, it shows he has very proper feeling!”

“Well, he hasn’t!” said Abby. “He didn’t know his nephew was in Bath, and he hasn’t any family feelings whatsoever!”

“Now, my love, how can you possibly—Don’t tell me you’ve actually met him?”

“He came to call on Mrs Grayshott while I was there—and was so obliging as to escort me home. Quite Gothic!”

“I don’t think it in the least Gothic,” asserted Selina. “It gives me a very good opinion of him! Just like his nephew, whose manners are so particularly pleasing!”

“From all you have told me about his nephew, Mr Miles Calverleigh is nothing like him!” said Abby, with an involuntary choke of laughter. “He is neither handsome nor fashionable, and his manners are deplorable!”

Selina, regarding her with real concern, said: “Dearest, I am persuaded you must be yielding to prejudice, and indeed you should not, though, to be sure, dear Rowland was always used to say it was your besetting sin, but that was when you were a mere child, and perfectly understandable, as I told Rowland, because one cannot expect to find young heads—no, I mean old heads on young shoulders—not that I should expect to find heads on any shoulders at all, unless, of course, it was a freak! Which I know very little about, because you must remember, Abby, that dear Papa had the greatest dislike of fairs, and would never permit us to go to one. Now, what in the world have I said to cast you into whoops?”

“Nothing in the world, Selina!” Abby said, as well as she could for laughter. “On—on the contrary! You’ve t-told me that in spite of all my f-faults I’m not a freak!”

“My dear, you allow your love of drollery to carry you too far,” said Selina reprovingly. “There has never been anything like that in our family!”

Overcome by this comforting assurance, Abby fled, conscious of a wish that Mr Calverleigh could have been present to share her amusement.

Selina continued to speculate, in her rambling way, throughout dinner, on his probable character, what he had done to deserve being banished, and what had brought him back to England; but Fanny’s arrival, just before the tea-tray was brought in, gave the conversation a welcome turn. Fanny was. full of the quaint or the beautiful things Oliver Grayshott had brought home from India, and although Selina’s interest in ivory carvings or Benares brass might be tepid, the first mention of Cashmere shawls, and lengths of the finest Indian muslin, aroused all her sartorial instincts; while a minute description of the sari caused her to wonder how long it would be before she dared venture out of doors, and to adjure Fanny to beg Lavinia not to have it made up until she had seen it. “For you know, my dear, excellent creature though she is, dear Mrs Grayshott has no taste, and what a shocking thing it would be if such an exquisite thing were to be ruined!”

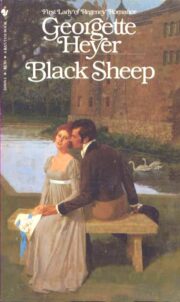

"Black Sheep" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Black Sheep". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Black Sheep" друзьям в соцсетях.