“James! Well! Such a surprise! I hadn’t the least notion—and only a fricassee of rabbit and onions for dinner! Now, if only I had known! But Betty or Jane can go into town, and procure some partridges, or perhaps a haunch of venison, which Fletching dresses very well, and is something you were always partial to.”

But James was not staying to dine with his sisters. He was returning to London on the Mail Coach.

Dismayed, Selina faltered: “Not staying? But, James—! You brought your cloak-bag! Mitton has carried it up to your room, and means to unpack it as soon as the bed has been made up!”

“Desire him to bring it down again, if you please. It was my intention to have put up here for a night, but what I have learnt since I entered this room has shocked me so much—I may say, appalled me!—that I prefer to return to London!”

“Good God!” uttered Selina, casting a wildly enquiring look at Abby. “You cannot mean—oh, but Abby has told you surely,that we believe there is no danger to be apprehended now? There has been no continued observance: the wretch has only once called since dear Fanny took ill, and with my own eyes I have seen the Creature he is making up to!”

“I am not referring to young Calverleigh,” said James stiffly “I came to Bath in the hope of discovering that the very disturbing rumours which have reached me had little foundation in truth. Instead, I learn that your sister has become infatuated with a man who should never have been permitted to cross your threshold!”

“No, no! Oh, pray do not say such things, James!” begged Selina faintly. “He is perfectly respectable, though I cannot like the way he dresses—so very careless, and coming to pay us a formal visit in top-boots!—and, of course, he must have been sadly rackety when he was young, to have been sent away to India—not that I think it was right to do such a cruel thing, for I don’t, and I never shall, and I consider it to be most unjust to say that he ought not to have been allowed to cross the threshold after all these years of being condemned to live in India, which may be a very interesting place, but is most unhealthy, and has burnt him as brown as a nut! And Abby is as much your sister as mine!”

“If Abby is so lost to propriety, to all sense of the duty she owes her family, as to marry Calverleigh, she will no longer be a sister of mine!” he said terribly.

“That’s no way to dissuade me!” said Abby.

“No, no, dearest!” implored Selina. “Pray don’t—! James didn’t mean it!”

“When you have heard what I have to say, Selina—”

“Yes, but not now!” said Selina, much agitated. “Mitton is fetching up the sherry, and I must take off my hat and my pelisse, and then it will be time for luncheon, which we always have, you know—just a baked egg, or a morsel of cold meat—and afterwards, when you are calmer,and we shan’t be interrupted, which is always so vexatious when one is enjoying a serious discussion. No, I don’t mean that! Not enjoying it, because already I am beginning to feel a spasm!”

James eyed her a little uneasily, and said, in a milder voice: “Very well, I will postpone what I have to say. I do not myself partake of luncheon, but I should be glad of a cup of tea.”

“Yes dear, of course, though I am persuaded it would do good to eat a mouthful of something after your journey!”

“Don’t press him, Selina! he’s bilious,” said Abby.

“Bilious! Oh, then, no wonder—!” cried Selina, her countenance lightening. “I have the very thing for you, dear James! I will fetch it directly, but on no account sherry!”

She then fled from the room, paying no heed to his exasperated denial of biliousness.

“Take care, James!” said Abby maliciously. “You will find yourself in the suds if you throw Selina into strong convulsions!”

He cast her a repulsive glance. “Spare me any more of your levity, Abigail! I shall say no more until after luncheon.”

“You won’t say any more to me at any time,” replied Abby. “You have already said too much! You may not have noticed it, but the sun came out half an hour ago. What I am going to do after luncheon, dear James, is to take Fanny out for a drive!”

With these words, accompanied by a smile of great sweetness, she went away to inform Fanny of the treat in store for her.

Fanny was also suffering from agitation. She turned an apprehensive, suspicious face towards her aunt, and said: “How long does my uncle mean to remain here? I don’t want to see him !”

“Have no fear, my love!” said Abby cheerfully. “Your uncle is equally reluctant to see you! I told him you were still infectious.”

Fanny gave a spontaneous laugh. “Oh, Abby! What a fib!”

“Yes, it weighs heavily on my conscience, but I don’t grudge a fib or two to save you from what I cannot myself endure. Grimston will bring a tray to you. I must send a message to the stables now.”

But in the end it was not Abby who took Fanny for her drive, but Lavinia Grayshott. Just as Abby was preparing to take her place in the barouche beside Fanny, Lavinia came running up, and exclaimed breathlessly: “Oh famous! Going out at last! Now you will soon be better! Oh, Miss Abby, I beg your pardon!—how do you do? I was coming to see Fanny, just to bring her this book! Oh, and, Fanny, take care how you open it! There’s an acrostic in it, from Oliver!”

Abby saw the brightening look in Fanny’s face, and realized that Fanny would prefer Lavinia’s company to hers. The knowledge caused her to feel a tiny heartache, but she did not hesitate. She said, smiling at Lavinia: “Why don’t you go with Fanny in my place? Would you like to?”

The answer was to be read in Lavinia’s face. “Oh—! But you, ma’am? Don’t you wish to go with her?”

“Not a bit!” Abby said. “I have a thousand and one things to do, and shall be glad to be rid of her! The carriage shall take you home, so if Martha sees no objection I shall resign Fanny into your charge.”

Martha, following more slowly in Lavinia’s wake, readily consented to the scheme; so Lavinia jumped into the carriage. Before it drew out of sight, Abby saw the two heads together, and guessed that confidences were already being exchanged. She stifled a sigh, as she turned back into the house. Between herself and Fanny there was constraint, for Fanny knew her to be hostile to Stacy Calverleigh. Well, perhaps she would unburden herself to Lavinia, and feel the better for it.

Chapter XVI

Belatedly following Selina’s advice, Abby retired to her bed-room to lie down. Contrary to her expectation, she fell asleep almost at once, and was still sleeping when James left the house.

When she awoke it was almost five o’clock, and the house was very quiet. She encountered Mrs Grimston on the landing, and learned from her that Miss Fanny was in the drawing-room, and seemingly none the worse for her drive; and that Miss Selina had gone up to rest as soon as Mr James had taken himself off. These words had a sinister ring, but as they were not followed by any mention of spasms or palpitations, and no distressing sounds could be heard emanating from Selina’s room, Abby hoped that they had been inspired merely by Mrs Grimston’s dislike of James. She went on down the stairs, and found Fanny with her head bent over the novel Lavinia had bestowed on her. She glanced up when Abby came into the room, and it struck Abby immediately that she was looking pale, and that her perfunctory smile was forced.

“Not tired, my darling?” she asked.

“No, thank you. No, not at all! I am reading the book Lavvy brought me: it is the most exciting story! I can’t put it down!”

But it did not seem to Abby, as she occupied herself with embroidery, and covertly observed her niece between the setting of her stitches, that the book was holding Fanny absorbed. She was using it as a shield. The suspicion that Lavinia’s indiscreet tongue had been at work crossed Abby’s mind. As she presently folded her work, she said: “Going to sit up for dinner, Fanny?”

“Oh!” Fanny gave a little start. “Oh, is it dinner-time already? Yes—I don’t know—Oh, yes! I’m not ill now!”

Abby smiled at her. “ Of course you’re not, but you have been out for the first time today, and it wouldn’t surprise me to learn that Lavinia has chattered you into a headache! A dear girl, but such a little gabster!”

She was now sure that Lavinia had been tattling. Fanny’s chin came up, and her eyes were at once challenging and defensive. “Oh, I don’t regard her!” she said, with a pathetically un-convincing laugh. “She is always full of the marvellous, but—but very diverting, you know!”

Yes, thought Abby, Lavinia has poured the tale of Stacy’s perfidy into her ears, and although she does not quite believe it she is afraid it may be true.

Her impulse was to take Fanny in her arms, petting and comforting her as she had so often done in the past, but a new and deeper understanding made her hesitate.

“If you please, Miss Abby,” said Fardle ominously, from the doorway, “I should wish to have a word with you, if convenient!’

“Why, certainly!” Abby said, with a lightness she was far from feeling. She followed Fardle out of the room, and asked: “What is it?”

The eldest Miss Wendover’s devoted handmaid fixed her with an eye of doom, and delivered herself of a surprising statement “I feel it to be my duty to tell you, Miss Abby, that I don’t like the look of Miss Selina—not at all I don’t!”

“Oh!” said Abby weakly. “Is—is she feeling poorly? I will come up to her.”

“Yes, miss. I was never one to make a mountain out of a molehill, as the saying is,” stated Fardle inaccurately, “but it gave me quite a turn when I went to dress Miss Selina not ten minutes ago. It is not for me to say what knocked her up, Miss Abby, and I hope I know my duty better than to tell you that it’s my belief it was Mr James that burnt her to the socket. All I know is that no sooner had he left the house than she went up to her room, saying she was going to rest on her bed, which was only to be expected. But when I went up to her she wasn’t on her bed, nor hadn’t been, as you will see for yourself, miss. And hardly a word did she speak, except to say she wouldn’t be going down to dinner, and didn’t want a tray sent up to her. Which is not like her, Miss Abby, and can’t but make one fear that she’s going into a Decline.”

On this heartening suggestion, she ushered Abby into Selina’s room. Kindly but firmly shutting the door upon her, Abby looked across the room at her sister, who was seated motionless beside the fire, with a shawl huddled round her shoulders, and a look in her face which Abby had never seen there before.

“Selina! Dearest!” she said, going quickly forward, to drop on her knees, gathering Selina’s hands into her own. Selina’s eyes turned towards her in a stunned gaze which alarmed Abby far more than a flood of tears would have done. “I have been thinking,” she said. “Thinking, and thinking ... It was my fault. If I hadn’t invited her to our party she wouldn’t have written such things to Cornelia.”

“Nonsense, dearest!” Abby said, gently chafing her hands. “Now, you know you promised me you wouldn’t say another word about That Woman!”

She had hoped to have coaxed a smile out of Selina, but after staring at her uncomprehendingly Selina uttered: “It was because I was cross! That was why you said you would marry him, wasn’t it? But I didn’t mean it, Abby, I didn’t mean it!”

“Goose cap! I know you didn’t!”

Selina’s thin fingers closed round her own like claws. “James said—But I told him it was no such thing! He put you all on end, didn’t he? I guessed how it must have been. I told him. I said that there was no question of—I said you would never dream of marrying Mr Calverleigh. And you wouldn’t, would you, Abby?”

Meeting Selina’s strained, searching eyes, Abby hesitated, before saying: “My dear, why put yourself into such a taking? I thought you wished me to marry?”

“Not Mr Calverleigh! I never wished it, except for your sake, but I thought, if you married Mr Dunston—so kind—in every way so suitable—and everyone would have been pleased, and you wouldn’t have gone away from me, not quite away from me, because I might have seen you every day—”

“Selina, I shall never go quite away from you,” Abby said quietly. “This is the merest agitation of nerves! You have let James talk you into high fidgets. In spite of his top-boots, and his careless ways, you don’t dislike Mr Calverleigh. Why, it was you who first said how unjust it was to condemn him for the sins of his youth!”

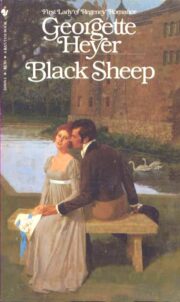

"Black Sheep" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Black Sheep". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Black Sheep" друзьям в соцсетях.