“Sent for me?” interrupted Stacy.

“Did I say sent for you? It must have been a slip of the tongue. Begged for the honour of your company!”

“I cannot imagine why,” muttered Stacy resentfully.

“Just on a matter of business. I want two things from you: one is an equity of redemption; the other is Danescourt—by which is to be understood the house, and the small amount of unencumbered land on which it stands. For these I am prepared to forgo the interest owing on the existent mortgages, and to pay you fifteen thousand pounds.”

Stacy was so thunderstruck by these calmly spoken words that his brained whirled. He almost doubted whether he had heard his uncle aright, for what he had said was entirely fantastic. Feeling dazed and incredulous, he watched Miles stroll over to the fire, and take a spill from a jar on the mantelpiece. He found his voice, but only to stammer: “B-but—equity of redemption—why, that means—Damn you, is this your notion of a joke?”

“No, no, I never cut jokes in business!” replied Miles. He came back to his chair, a lighted cheroot between his fingers, and sat down again, stretching his long legs out before him, with one ankle crossed over the other, after his usual fashion. He regarded his stunned nephew with mild amusement, and said: “I’m a very rich man, you know.”

Since Stacy knew nothing of the sort, he felt more strongly than before that he had strayed into a world of fantasy. “I don’t believe it!” he blurted out

“I am afraid,” said Miles, apologetically, “that you have been misled into thinking that because I’ve no fancy for rigging myself out in the first style of elegance, cutting a dash, or saddling myself with a multitude of things I haven’t the least wish to possess, I must be as cucumberish as you are yourself. You should never judge by appearances, nevvy!”

It seemed monstrous to Stacy that his uncle should not have informed him that he was in affluent circumstances. He exclaimed hotly: “You have been deceiving me, then! Deliberately deceiving me!”

“Not at all. You deceived yourself. That isn’t to say that I wouldn’t have deceived you, had it been expedient to do so. But, to own the truth, it was of no consequence to me whether you thought me a Nabob or a Church rat. Except, of course,” he added reflectively, “that if you had known I was full of juice I should have found you an intolerable nuisance. You see, I never lend money without security.”

Stacy reddened, but said: “If you can indeed afford to buy up the mortgages—if you don’t wish to see Danescourt pass out of our hands—if you are willing to help me to bring myself about—we could come to some agreement! We could—” He broke off, encountering his uncle’s eyes, and seeing in them a look as implacable as the note he had detected in his voice. There was no smile in them, and no warmth; nor could he perceive in them anger, impatience, contempt, or any human emotion whatsoever. They were coldly dispassionate, and as hard as quartz.

“You know, you labour under too many misapprehensions,” said Miles pleasantly.

“But—Good God, you can’t dispossess me!”

“What makes you think so?”

“You wouldn’t! We are both Calverleighs! You are my uncle!”

“You have a remarkably false notion of my character if you think that that circumstance will prevail upon me to maintain Danescourt for your benefit. I can’t think where you came by it.”

The brief, vague vision of being able once more to draw upon his estates for his needs faded. Miles had spoken amiably, but with finality. Stacy was conscious of an unreasoning resentment. He said: “What is it to you? Much you care for being Calverleigh of Danescourt! Or is that it?”

“Oh, lord, no! I care for Danescourt, that’s all.”

“That’s what I said!”

“It’s not what you meant, or what I mean. I want Danescourt because I’m fond of it, and for the same reason I won’t see it fall into ruins. If I weren’t, I wouldn’t lift a finger to save it. All that fiddle-faddle you talk about being Calverleigh of Danescourt don’t mean a thing to me.”

“Coming it too strong, uncle! And just as well if it were true, for I am the head of the family, and while I’m alive I am Calverleigh of Danescourt!”

“Yes, yes!” said Miles, on a soothing note. “You can go on calling yourself Calverleigh of Danescourt, or anything else you like: I’ve no objection.”

“How the devil can I do so if I don’t own even the house?” demanded Stacy hotly. “I’ll sell you an equity of redemption, but I’ll not sell the house or the demesne!”

“Well, once I foreclose, you won’t have any choice in the matter, will you ? You’ll be glad to sell it to me at any figure I name.

Stacy stared at him, very white about the mouth. “You’d do that? Foreclose on me—your own nephew!—force me out of my very birthplace? My God, is that what you’ve been doing all these years? Waiting for the chance of revenge?”

“No, I’ve been far too busy. I wish you would rid your mind of its apparent conviction that I think myself hardly used. I don’t, and I never did. I didn’t like your grandfather, or your father either, but I’ve often been grateful to them for the good turn they didn’t know they’d done me. India suited me down to the ground. What’s more, if they hadn’t sent me there I might never have discovered that I had a turn for business. But I had, Stacy, and you’d do well to bear it in mind. When you prate to me about our relationship, you’re wasting your time. Sentiment has no place in business, even if I had any, which I haven’t. As for your talk about revenge,it’s balderdash! I don’t like you any more than I liked your father—in fact, less—but why the devil should I want to be revenged on you?”

“On him! Because I am his son!”

“Good God! You must have watched the deuce of a lot of melodramas in your time! Until I met you, I’d no feeling for you of any kind: why should I? If I had found Danescourt as I’d left it—or if I’d even found you making a push to restore it—I shouldn’t have interfered. But I didn’t. I had been warned of it, which was why I decided to come home, but I wasn’t prepared—”

“It wasn’t my fault!” Stacy said quickly, his colour surging into his face. “It was my father who granted the first mortgage. He was in Dun territory when he died, and how the devil could I—”

“Don’t excuse yourself! It makes no odds to me which of you let it fall into decay.”

“I should have been glad enough to set it in order, but I hadn’t the means!”

“No, and as you wouldn’t have spent a groat more than you were obliged to on it if you had had the means, and would sell it tomorrow, if you could find a fool willing to purchase a place which you described to me, on the occasion of our first meeting, as a damned barrack, mortgaged to the hilt, and falling into ruin besides, I am now going to relieve you of it.”

“You’d be better advised to leave it in my possession! What do you imagine will be said of you, if you—you usurp my place?”

“Well, according to Colonel Ongar, my arrival will be regarded in the light of a successful relieving force. You seem to have made yourself odious to the entire county.”

“Exactly as you did, in fact!”

“No, no, I was never odious! Merely a scapegrace! My youthful sins will be forgiven me the moment I remove the padlock from the main gate, and cut down that hayfield of yours. I must say, I don’t at all care for it.”

“Hayfield? What the devil—?”

“In my day it was the South Lawn.”

There was an uncomfortable silence. “So you’ve been there, have you?” Stacy said sullenly.

“Yes, I’ve been there. I thought poor old Penn was going to burst into tears. Mrs Penn did. Fell on my neck, too, and went straight off to kill a fatted calf. The return of the Prodigal Son was nothing to it. No, I don’t think I shall be shunned by the county, Stacy.”

Another silence fell, during which Stacy sat scowling down at the table. He said suddenly: “Fifteen thousand? Paltry!”

“Perhaps,” suggested Miles, “you are forgetting the little matter of the mortgages.”

Stacy bit his lip, but said: “It’s worth more—much more!”

“It is, in fact, worth much less. However, if you believe you can sell it for more, by all means make the attempt!”

“With you holding all the rest of the estate? Who the devil would buy a place like Danescourt with no more land attached to it than the gardens, and the park?”

“I shouldn’t think anyone would.”

“Brought me to Point Non-Plus, haven’t you?” said Stacy, with an ugly laugh.

“You’re certainly there, but what I had to do with it I don’t know.”

“You could help me to make a recover—give me time!”

“I could. I could also ruin you. I don’t choose to do either—though when I saw Danescourt I was strongly tempted to let you take up residence in the King’s Bench Prison, and leave you to rot there! Which is what you will do, if you refuse my offer.”

“Oh, damn you, I can’t refuse it! How soon can I have the blunt?”

“As soon as the conveyance is completed. The necessary documents are being prepared, and you will find them with my lawyer. I’ll furnish you with his direction. You had better take your own man with you, to see all’s right, by the way.”

“I shall certainly do so! And I shall be very much obliged to you if you’ll advance me a hundred, sir, at once!”

“I’ll make you a present of it,” said Miles, drawing a roll of bills from his pocket,

“You’re very good!” said Stacy stiffly. “Then, if there’s nothing more you wish to say, I’ll bid you goodnight!”

“No, nothing,” replied Miles. “Good night!”

Chapter XVIII

Since Miss Butterbank, after a night and the better part of a day enduring the agonies of violent toothache, was closeted with the dentist when Mr Miles Calverleigh returned to Bath, the news of his arrival was not carried to Sydney Place until several hours after he had made an unexpected descent upon Miss Abigail Wendover.

He took her entirely by surprise. Not only did he present himself at an unusually early hour, but when Mitton admitted that he rather thought Miss Abigail was at home he said that there was no need to announce him, and ran up the stairs, leaving Mitton in possession of his hat and malacca cane, and torn between romantic speculation and disapproval of such informal behaviour.

Abby was alone, and engaged on the task of fashioning a collar out of a length of broad lace. The table in the drawing-room was covered with pins, patterns, and sheets of parchment, and Abby had just picked up a pair of shaping scissors when Mr Calverleigh walked into the room. She glanced up; something between a gasp and a shriek escaped her; the scissors fell with a clatter; and she started forward involuntarily, with her hands held out. “You’ve come back! Oh, you have come back!” she cried.

The unwisdom, and, indeed, the impropriety of this unguarded betrayal of her sentiments occurred to her too late, and did not seem to occur to Mr Calverleigh at all. Before she could recover herself she was in his arms, being kissed with considerable violence. “My bright, particular star!” uttered Mr Calverleigh, into her ear.

Mr Calverleigh had very strong arms, and a shoulder most conveniently placed for the use of a tall lady. Abby, gasping for breath, gratefully leaned her cheek against it, feeling, for a fewbrief moments, that she had come safely to harbour after a stormy passage—She said, clinging to him: “Miles! Oh, my dear, I’ve missed you so dreadfully!” But hardly had she uttered these words than all the difficulties of her situation rushed in upon her, with the recollection of the decision she had so painfully reached, and she said, trying to wrench herself free: “No! Oh, I can’t think what made me—! I can’t, Miles, I can’t!”

Mr Calverleigh, that successful man of affairs, was not one to be easily rocked off his balance. “What can’t you, my heart’s dearest?” he enquired.

Abby quivered. “Marry you! Oh, Miles, don’t!”

She broke from him, and turned away, groping blindly for her handkerchief, and trying very hard not to let her emotion get the better of her.

“Well!” said Mr Calverleigh, in stunned accents. “This is beyond everything! After what has just passed between us! I wonder you dare look me in the face!”

Abby, was not, in fact, daring to look him in the face: she was occupied in drying her wet cheeks.

“Has no one ever told you that it is the height of impropriety to kiss any gentleman, unless you have the intention of accompanying him immediately to the altar?” demanded the outraged Mr Calverleigh. “It will not do, ma’am! Such conduct—”

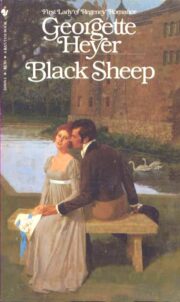

"Black Sheep" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Black Sheep". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Black Sheep" друзьям в соцсетях.