“Ah, I never had any sisters, and my mother died when I was a schoolboy.”

“You are much to be pitied,” she said.

“Oh, no, I don’t think so!” he replied. “I don’t like obligations.” The disarming smile crept back into his eyes, as they rested on her face. “My family disowned me more than twenty years ago, you know!”

“Yes, I did know. That is—I have been told that they did,” she said. She added, with the flicker of a shy smile: “I think it was a dreadful thing to have done, and—and perhaps is the reason why you don’t wish to meet your nephew?”

That made him laugh. “Good God, no! What concern was it of his?”

“I only thought—wondered—since it was his father—”

“No, no, that’s fustian!” he expostulated. “You can’t turn me into an object for compassion! I didn’t like my brother Humphrey, and I didn’t like my father either, but I don’t bear them any grudge for shipping me off to India. In fact, it was the best thing they could do, and it suited me very well.”

“Compassion certainly seems to be wasted on you, sir!” she said tartly.

“Yes, of course it is. Besides, I like you, and I shan’t if you pity me.

She was goaded into swift retort. “Well, that wouldn’t trouble me!”

“That’s the barber!” he said appreciatively. “Tell me more about this niece of yours! I collect her mother’s dead too?”

“Her mother died when she was two years old, sir.”

There was an inscrutable expression in his face, and although he kept his eyes on hers the fancy struck her that he was looking at something a long way beyond her. Then, with a sudden, wry smile, he seemed to bring her into focus again, and asked abruptly: “Rowland did marry her, didn’t he?—Celia Morval?”

“Why, yes! Were you acquainted with her?”

He did not answer this, but said: “And my nephew is dangling after her daughter?”

“I am afraid it is more serious than that. I haven’t met him, but he seems to be a young man of considerable address. He has succeeded in—in fixing his interest with her—well, to speak roundly, sir, she imagines herself to be violently in love with him. You may think that no great matter, as young as she is, but the thing is that she is a high-spirited girl, and her character is—is determined. She has been virtually in my charge—and that of my eldest sister—from her childhood. Perhaps she has been too much indulged—granted too much independence. I was never used to think so—you see, I was myself—we all were!—brought up in such subjection that I vowed I wouldn’t allow Fanny to be crushed as we were. I even thought—knowing how much I was used to long for the courage to rebel, and how bitterly I resented my father’s tyranny—that if I encouraged her to be independent, to look on me as a friend rather than as an aunt, she wouldn’t feel rebellious—would allow herself to be guided by me.”

“And she doesn’t?” he asked sympathetically.

“Not in this instance. But until your nephew bewitched her she did! She’s the dearest girl, but I own that she can be headstrong, and too impetuous.” She paused, and then said ruefully: “ Once she makes up her mind it is very hard to turn her from it. She—she isn’t a lukewarm girl! It is one of the things I particularly like in her, but it is quite disastrous in this instance!”

“Infatuated, is she? I daresay she’ll recover,” he said, a suggestion of boredom in his voice.

“Undoubtedly! My fear is that she may do so too late! Mr Calverleigh, if your nephew were the most eligible bachelor in the country I should be opposed to the match! She is by far too young to be thinking of marriage. As it is, I need not, I fancy, scruple to tell you that he is not eligible! He bears a most shocking reputation, and, apart from all else, I believe him to be a fortune-hunter!”

“Very likely, I should think,” he nodded.

This cool rejoinder made it necessary for her to keep a firm hand on the rein of her temper. She said, in a dry voice: “ You may regard that with complaisance, sir, but I do not!”

“No, I don’t suppose you do,” he agreed amiably.

She flushed. “And—which is of even more importance!—nor does my brother!”

This seemed to revive his interest. A gleam came into his eyes. “What, does he know of this?”

“Yes, sir, he does know of it, and nothing, I assure you, could exceed his dislike of such a connection! It was he who told me what had been happening here, in Bath, during my absence, having himself learnt of it through someone who chances to be a close friend of his wife. He posted up to London from Bedfordshire to appraise me of it. Pray do not think I exaggerate when I say that I have seldom seen him more profoundly shocked, or—or heard him express himself with so much violence! Believe me, sir, nothing could prevail upon him to give his consent to your nephew’s proposal!”

“I do—implicitly!” he replied, the light of unholy amusement in his eyes. “What’s more, I’d give a monkey to have seen him! Lord, how funny!”

“It was not in the least funny! And—”

“Yes, it was, but never mind that! Why should you fall into a fuss ? If the virtuous James forbids the banns, and if my nephew is a fortune-hunter, depend upon it he will cry off!” He saw the doubt in her face, and said: “You don’t think so?”

She hesitated. “I don’t know. It may be that he hopes to win James over—”

“Well, he won’t do that!”

“No. Unless—Mr Calverleigh, I have reason—some reason—to fear that he might persuade her into an elopement! Thinking that once the knot was tied my brother would be obliged—”

She stopped as he broke into a shout of laughter, and said indignantly: “It may seem funny to you, but I promise you—”

“It does! What a subject for a roaring farce! History repeats itself—with a vengeance!”

Wholly bewildered, she demanded: “What do you mean? What can you possibly mean?”

“My pretty innocent,” he said, in a voice of kindness spiced with mockery, “did no one ever tell you that I am the man who ran off with your Fanny’s mother?”

Chapter IV

It was a full minute before Abby could collect her startled wits enough to enable her to speak, and when she did speak it was not entirely felicitously. She exclaimed: “Then I was right! And you are it!”

With every appearance of enjoyment, he instantly replied: “ Until I know what it signifies, I reserve my defence.”

“The skeleton in the cupboard! Only I told Selina it would prove to be no more than the skeleton of a mouse!”

“You lied, then! The skeleton of a black sheep if you wish, but not that of a mouse—even a black mouse!”

Her voice quivered on the edge of laughter. “No, indeed! How—how very dreadful! But how—when—Oh, do, pray, tell me!”

“You shock me, Miss Abigail Wendover!—you know, I do like that name!—Who am I to divulge the secret which has been so carefully guarded?”

“The skeleton, of course!”

“But skeletons don’t talk!” he pointed out.

Preoccupied with her own thoughts, she paid no heed to this, but said suddenly: “That was why James flew into such a stew! Now, isn’t it like James not to have told me the truth?”

“Exactly like him!”

“But why didn’t George—No, you may depend upon it that he didn’t know either! Because Mary doesn’t, though she has always suspected, as I did, that there was something about Celia which was being kept secret. I wonder if Selina knew? Not the whole, of course, for if she had she would never have encouraged your nephew, would she?”

“Oh, no! She wouldn’t, and very likely Mary wouldn’t either, but George,I feel, is another matter. Do enlighten me! Who are these people?”

She blinked. “Who—? Oh, I beg your pardon! I have been running on in the stupidest way!—talking to myself! Selina is my eldest sister: we live together, in Sydney Place; Mary is my next sister: next in age, I mean; and George Brede is her husband. Never mind that! When did you run off with Celia?”

“Oh, when she became engaged to be married to Rowland!” he answered, very much as if this were a matter of course.

“Good God! Do you mean that you abducted her?” she gasped.

“No, I don’t recall that I ever abducted anyone,” he said, giving the matter his consideration. “In fact, I’m sure of it. An unwilling bride would be the very devil, you know.”

“Well, that’s precisely what I’ve always thought!” she exclaimed, pleased to find her opinion shared. “Whenever I’ve read about it, in some trashy romance, I mean. Of course, if the heroine is a rich heiress the case is understandable, but—Oh!” Consternation sounded in her voice; painfully mortified, she stammered: “I beg your pardon! I can’t think what made me say—”

“Not at all!” he assured her kindly. “A very natural observation!”

“Do you mean to tell me that that was why you—you ran off with Celia?” she asked incredulously.

“Well, no! But you must remember that I was very young in those days: halflings seldom have an eye to the main chance. It was All for Love, or the World Well Lost. We fell passionately in love—or, at any hand, we thought we did. You know, this is a damned sickly story! Let us talk of something else!”

“I think it is a sad story. But I don’t perfectly understand how it was that Celia became engaged to my brother if she was in love with you?”

“Don’t you? You should! Were you acquainted with Morval?”

She shook her head. “I might perhaps have seen him, but I don’t recall: I was only a child at that time. I know he was one of my father’s closest friends.”

“Then you ought to be able to form a pretty accurate picture of him. They were as like as fourpence to a groat. The match was made between them. Celia was forbidden ever again to favour me with as much as a common bow in passing—mind you, I wasn’t at all eligible—and ordered to accept Rowland’s offer.”

“I understand her submission to the first order, but not to the second! I too submitted in a like case. It is not an easy matter to marry against the will of one’s parents. But, with one’s affections engaged, to accept another man’s offer, merely because one’s father wished it, is something I do not understand! If Celia was ready to elope with you she must have been a girl of spirit, too, and not in the least the meek, biddable creature we always thought her!”

“Oh, no, she hadn’t an ounce of steel in her!” he said coolly. “She was romantical, though, and certainly biddable: one of those pretty, clinging females who invariably yield to a stronger will! I hadn’t the wit to perceive it, until the sticking point was reached, and she knuckled down in a flood of tears. And a very good thing she did,” he added. “We might have carried it, if she had stood buff, and I should have been regularly in for it I didn’t think so at the time, of course, but I was never nearer to dishing myself. How did she deal with Rowland?”

He had stripped the affair of all its romantic pathos, but Abby could not help wondering whether his apparent unconcern hid a bruised heart. She answered his casual question reticently: “I don’t know. I wasn’t of an age to know. She was always rather quiet, but she never appeared to be unhappy. I see now that she can’t have loved Rowland, but I do know that she held him in the greatest respect I mean, she depended wholly on his judgment, and was for ever saying Rowland says,as though that was a clincher to every argument!”

The slightly acid note on which she ended made him laugh. “An opinion not shared by Abigail Wendover, I apprehend!”

“No!” she returned, her eyes kindling reminiscently. “It was not shared by me! Rowland was a—” She stopped, resolutely shutting her lips together.

“Rowland,” said Miles Calverleigh, stepping obligingly into the gap, “was a pompous lobcock!”

“Yes!” said Abby, momentarily forgetting herself. “That is exactly what he was! The most consequential, pot-sure—” Again she broke off short, adding hastily: “Never mind that!”

“I don’t—and it seems that Celia didn’t either. No, she wouldn’t, of course. You know, the more I think of it the more I feel that they must have been made for each other! Well, I’m glad to know she didn’t fall into a green and yellow melancholy.”

Abby’s brow was wrinkled. “Yes, but—Did Rowland know of—of the elopement ?”

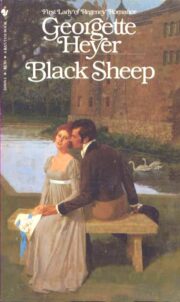

"Black Sheep" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Black Sheep". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Black Sheep" друзьям в соцсетях.