The tide was outland in the evening light I saw those malignant rooks jutting cruelly out of the shallow water.

And there half a mile ahead of us was Pendorric itself, and I caught my breath for it was awe-inspiring. It towered above the sea a massive rectangle of grey stone, with crenellated towers and an air of impregnability, noble and arrogant as though defying the sea and the weather and anyone who came against it.

” This is your home, my dear,” said Roc, and I could hear the pride in his voice.

” It’s … superb.”

” So you’re not unhappy? I’m glad you’re seeing it for the first time.

Otherwise I might have thought you married it rather than me. “

” I would never marry a house! “

” No, you’re too honest—too full of common sense … in fact too wonderful. That’s why I fell in love with you and determined to marry you.”

We were roaring uphill again, and now that we were closer the house certainly dominated the landscape. There were lights in some of the windows and I saw the arch leading to the north portico.

“The grounds,” Roc explained, “are on the south side. We can approach the house from the south; there are four porticoes—north, south, east and west. But we’ll go into the north tonight because Morwenna and Charlie will be waiting for us there. Why, look,” he went on, and following his gaze I saw a slight figure in riding breeches and scarlet blouse, black hair flying, running towards us. Roc slowed the car and she leapt on to the running-board. Her face was brown with sun and weather, her eyes were long and black and very like Roc’s. ” I wanted to be the first to see the bride!” she shouted. ” And you always get your way,” answered Roc. ” Favel, this is Lowella, of whom beware.”

” Don’t listen to him,” said the girl. ” I expect I’ll be your friend.”

” Thank you,” I said. ” I hope you will.”

The black eyes studied me curiously. ” I said she’d be fair,” she went on. ” I was certain.”

“Well, you’re impeding our progress,” Roc told her. ” Either hop in or get off.”

” I’ll stay here,” she announced. ” Drive in. ” Roc obeyed and we went slowly towards the house.

“They’re all waiting to meet you,” Lowella told me.

“We’re very excited. We’ve all been trying to guess what you’ll be like. In the village they’re all waiting to see you too. Every time one of us goes down they say, ” And when will the Bride be coming to Pendorric? “

” ” I hope they’ll be pleased with me. “

Lowella looked at her uncle mischievously and I thought again how remarkably like him she was. ” Oh, it was time he was married,” she said. ” We were getting worried.”

” You see I was right to warn you,” put in Roc. ” She’s the enfant terrible.”

” And not such an infant,” insisted Lowella. ” I’m twelve now, you know.”

“You ‘grow more terrible with the years. I tremble to think what you’ll be like at twenty.”

We had now passed through the gates and I saw the great stone arch looming ahead. Beyond it was a portico guarded on either side by two huge carved lions, battered by the years but still looking fierce as though warning any to be wary of entering.

And there was a woman—so like Roc that I knew she was his twin sister—and behind her a man, whom I guessed to be her husband and father of the twins.

Morwenna came towards the car. ” Roc! So you’re here at last. And this is Favel. Welcome to Pendorric, Favel.”

I smiled up at her, and for those first moments I was glad that she looked so like Roc, because it made me feel that she was not quite a stranger. Her dark hair was thick with a slight natural wave and it grew to a widow’s peak which in the half-light gave the impression that she was wearing a sixteenth-century cap. She wore a dress of emerald-green linen which became her dark hair and eyes. and there were gold rings in her ears.

” I’m so glad to meet you at last,” I said. ” I do hope this isn’t a shock to you.”

” Nothing my brother does ever shocks us, really, because we’re expecting surprises.”

” You see I’ve brought them up in the right way,” said Roc lightly. ” Oh and here’s Charlie.”

My hand was gripped so firmly that I winced. I was hoping Charles Chaston didn’t notice this as I looked up into his plump bronzed face.

” We’ve all been eagerly waiting to see you, ever since we heard you were coming,” he told me.

I saw that Lowella was dancing round us in a circle; with her flying hair, and as she was chanting something to herself which might have been an incantation, she reminded me of a witch, “Oh Lowella, do stop,” cried her mother with a little laugh.

“Where’s Hyson?”

Lowella lifted her arms in a gesture which implied she had no idea. ” Go and find her. She’ll want to say hallo to her Aunt Favel.”

“We’re not calling her aunt,” said Lowella.

“She’s too young. She’s just going to be Favel. You’ll like that better, won’t you, Favel?”

” Yes, it sounds more friendly.”

” There you see,” said Lowella, and she ran into the house. Morwenna slipped her arm through mine, and Roc came up and took the other as he called: “Where’s Toms? Tom's Come and bring in our baggage.”

I heard a voice say: ” Ay sir. I be coming.”

But before he appeared Morwenna and Roc were leading me through the portico, and with Charles hovering behind we entered the house. I was in an enormous hall at either end of which was a beautiful curved staircase leading to a gallery. On the panelled walls were swords and shields and at the foot of each staircase a suit of armour. ” This is our wing,” Morwenna told me. ” It’s a most convenient house, really, being built round a quadrangle. It is almost like four houses in one and it was built with the intention of keeping Pendorrics together in the days of large families. I believe years ago the house was crowded. Only a few servants lived in the attics; the rest of them were in the cottages. There are six of them side by side, most picturesque and insanitary—until Roc and Charles did something about it. We still draw on them for help; and we only keep Toms and his wife and daughter Hetty, and Mrs. Penhalligan and her daughter Maria, living in. A change from the old days. I expect you’re hungry.” I told her we had had dinner on the train.

” Then well have a snack later. You’ll want to see some thing of the house, but perhaps you’d like to go to your own part first.” I said I should, and as I spoke, my eye was caught by a portrait which hung on the wall of the gallery. It was a picture of a fair-haired young woman m a clinging blue gown which showed her shapely shoulders; her hair was piled high above her head and one ringlet hung over her shoulder. She clearly belonged to the late eighteenth century, and I thought that her picture, placed as it was, dominated the gallery and hall.

” How charming!” I said.

” Ah yes, one of the Brides of Pendorric,” Morwenna told me. There it was again—that phrase which I had heard so often. ” She looks beautiful … and so happy.”

” Yes, she’s my great-great-great… one loses count of the greats . grandmother,” Morwenna said. ” She was happy when that was painted, but she died young.”

I found it difficult to take my eyes from the picture because there was something so appealing about that young face.

” I thought, Roc,” went on Morwenna, ” that now you’re married you’d want the big suite.”

” Thanks,” Roc replied. ” That’s exactly what I did want.” Morwenna turned to me. ” The wings of the house are all connected. You don’t have to use the separate entrances unless you wish to. So if you come up to the gallery I’ll take you through.”

” There must be hundreds of rooms.”

“Eighty. Twenty in each of the four parts. I think it’s much larger than it was in the beginning. A lot of it has been restored, but because of that motto over the arch they’ve been very careful to make it seem that what was originally built has lasted.”

We went past the suit of armour and up the stairs to the gallery. ” One thing,” said Morwenna, ” when you know your own wing you know all the others; you just have to imagine the rooms facing different directions.”

She led the way, and with Roc’s arm still in mine we followed. When we reached the gallery we went through a side door which led to another corridor in which were beautiful marble figures set in alcoves, ” Not the best time to see the house,” commented Morwenna. ” It’s neither light nor dark.”

“She’ll have to wait till the morning to explore,” added Roc. I looked through one of the window down on to a large quadrangle in which grew some of the most magnificent hydrangeas I had ever seen. I remarked on them and we paused to look down.

” The colours are wonderful in sunlight,” Morwenna told me. ” They thrive here. It’s because we’re never short of rain and there’s hardly ever a frost. Besides, they’re well sheltered in the quadrangle.” It looked a charming place, that quadrangle. There was a pond, in the centre of which was a dark statue which I later discovered was of Hermes; and there were two magnificent palm trees growing down there so that it looked rather like an oasis in a desert. In between the paving-stones clumps of flowering shrubs bloomed and there were several white seats with gilded decorations.

Then I noticed all the windows which looked down on it and it occurred to me that it was a pity because one would never be able to sit there without a feeling of being over looked.

Roc explained to me that there were four doors all leading into it, one from each wing.

We moved along (he corridor through another door and Roc said that we were now in the south wing—our own. We went np a staircase and Morwenna went ahead of us, and when she threw open a door we entered a large room with enormous windows facing the sea. The deep red velvet curtains had been drawn back, and when I saw the seascape stretched out before me I gave a cry of pleasure and at once went to the window.

I stood there looking out across the bay; the cliffs looked stark and menacing in the twilight and I could just glimpse the rugged outline of the rocks. The smell and the gentle whispering of the sea seemed to fill the room.

Roc was behind me. ” It’s what everyone does,” he said. ” They never glance at the room ; they look at the view.”

” The views are just as lovely from the east and west side,” said Morwenna, ” and very much the same.”

She turned a switch and the light from a large chandelier hanging from the centre of the ceiling made the room dazzlingly bright. I turned from the window and saw the fourposter bed, with the long stool at its foot, the tallboy, the cabinets—all belonging to an eariier generation, a generation of exquisite grace and charm.

“But it’s lovely!

“I said.

” We flatter ourselves that we have the best of both worlds,” Morwenna told me. ” We made an old powder closet into a bathroom.” She opened a door which led from me bedroom and disclosed a modern bathroom. I looked at it longingly and Roc laughed.

” You have a bath,” he said. ” I’ll go and see what Toms is doing about the baggage. Afterwards we’ll have something to eat, and perhaps I’ll take you for a walk in the moonlight—if Acre’s any to be had.” I said I thought it was an excellent idea, and they left me.

When I was alone I went once more to the windows to gaze out at that magnificent view. I stood for some minutes, my eyes on the horizon, as I watched the intermittent flashes of the lighthouse.

Then I went into the bathroom, where bath salts and talcum powder had all been laid out for me—my sister-in-law’s thoughtfulness, I suspected. She was obviously anxious to make me welcome, and I felt it had been a very pleasant homecoming.

If only I could have thought of Father at work in his studio I could have been very happy. But I had to start a new life; I must stop fretting. I had to be gay. I owed that to Roc; and he was the type of man who would want his wife to be gay. I went into the bathroom, ran a bath and spent about half an hour luxuriating in it.

When I came out. Roc had not returned, but my bags had been put in the room. I unpacked a small one and changed from my suit to a silk dress; and I was doing my hair at the dressing-table, which had a three-sided mirror, when there was a knock at the door. ” Come in,” I called, and turning saw a young woman and a child. I thought at first that the child was Lowella and I smiled at her. She did not return the smile but regarded me gravely, while the young woman said:

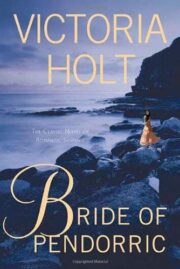

"Bride of Pendorric" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Bride of Pendorric". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Bride of Pendorric" друзьям в соцсетях.