The small stone house was lit by candles, the golden glow warm and inviting, the scent of lilies and roses permeating the rooms. Vases of flowers stood on tables and consoles, a cold supper had been left in the small dining parlor, the bed had been turned down in the tiny bedroom tucked under the eaves.

"Do you like it?" Hugh asked, holding her hand in his as they stood on the threshold of the bedroom.

"It's like a doll house or a fairy tale cottage."

"And quiet."

"Yes. But everyone seemed to be enjoying themselves. You're much loved."

"John and my steward see to most of it. They're very competent."

"They couldn't do it without your approval." She knew firsthand how brutal and uncaring authority could be.

"My tenants might as well enjoy some of the benefits of my wealth, too. I'll show you my farms at Alderly tomorrow. We're trying out some new crops and machinery."

She smiled, thinking how different the country marquis from his libertine persona. "I'd like that," she said.

"Is there anything else you'd like?" he murmured, bending to nibble on her ear.

"Supper in bed?" she teased. "I'm famished all the time."

"And you should be. I want my baby well fed," he lightly declared. "Now, lie down and I'll bring up food and feed you."

"Youare a darling."

"And you're the love of my life," he murmured, drawing her into his arms.

That night, after their supper and after they'd made love, much later when the moon was moving toward the horizon, he quietly said, holding her in his arms, "I want you to divorce your husband."

He felt her stiffen in his arms.

"I can have a divorce secured without fanfare. No one need know the details or circumstances. My lawyers will be discreet."

"My husband won't allow it."

"I'll see that he does." He spoke with an authority that had never been gainsaid.

"Let's talk about it in the morning. Would you mind?"

"No, of course not," he gently said. "I'll do whatever you wish. But you know I want this child to be legitimately mine."

"I know," she whispered, and, reaching up, she kissed him, tears welling in her eyes.

"Don't cry. I'll make everything right," he tenderly said, wiping her tears away with the back of his hand.

"I know you will." Her smile quivered for only a moment.

She was gone when he woke in the morning.

He tore the house apart, the village, the parish, searching for any clue to her whereabouts. He hired detectives from London, from Paris, but there was no Prince Marko and consort; he had every British consulate looking for her, too, without success. She'd disappeared, as if the earth had swallowed her up.

When he retired from the world shortly after, there was talk of various maladies and illnesses. Some said he'd turned hermit as penance for his numerous sins; those who knew him better saw his desperate pain and sorrow and worried for his sanity. But as the weeks turned into months, he came to accept Sofia 's disappearance as inevitable and the rhythm of his life settled into a pattern measured only by the seasons of the field and farm. He kept to his estate at Woodhill, although his closest friends would come to visit. He traveled to London only rarelyfor the marriage of his niece and later that of his friend Charles, or for business once or twice a year; he appeared at an occasional race meet when his stable was performing well, and his local hunt club enjoyed his presence regularly during the hunt seasonalthough the level of risks he took at the jumps reached such proportions, wagers were made on whether he'd survive the sport.

Two years passed, with the young marquis living a life so antithetical to his former existence, all the ladies of his acquaintance despaired of ever experiencing the pleasure of his company again. More determined than most of the pursuing women, the lovely Countess Greyson once managed to infiltrate his household and appeared in his bed.

He took one look at her, she later related, calmly remarked, "I prefer sleeping alone," and left his bedchamber without a backward glance. After that episode, he gave new orders to his staff concerning his privacy, and no one breached the gates of Woodhill without his approval.

One August afternoon, several months later, he was going through his daily correspondence, the study doors open to the warm sun and summer breeze. What was she doing right now? he wondered as he often did when opening the latest letter from the detective firm in Paris he still kept on retainer. Expecting no more than the usual quarterly invoice without any new information, he unfolded a brief note and lifted out a news page photo. "Is this the necklace?" his contact in Paris had written. Raising the scrap of paper closer, he gazed at the indistinct image. An arrow had been drawn on the newsprint, indicating a woman in the background at a soiree for the Austrian ambassador in Paris.

Her face rose out of the crowd and his heart seemed to stop.

Cautioning himself against rash hope, he quickly scrutinized the photogravure. The woman was blonde; the hair color changed Sofia 's looks but the eyes were hers, and the perfect mouth. His gaze moved to the highlighted necklace, and his last present to Sofia glittered at her throat. Suddenly the blonde hair altered in his mind's eye to a rich, warm auburn and the woman in the background of the thronged soiree stepped from the page back into his life.

He left Woodhill within twenty minutes and was crossing the Channel five hours later. When the detective bureau opened in Paris the next morning, he was waiting at the door, having just arrived from the Gare du Nord, unshaven, disheveled, demanding immediate answers.

It took the remainder of the day to track down enough people in the photo to positively identify the woman with the diamond necklace.

She turned out to be Princess Mariana, regent of a small principality on the border of Dalmatia and Montenegro. Her son, for whom she ruled, was the young Prince Sava.

His journey took him from Paris to Salzburg to Zagreb. The train traveled through countryside dark with floods outside Zagreb before coming to the Adriatic, which looked that day like one of the bleak Scottish lochs. Sky, islands, and sea were all merged into the gray mist and sweeping rain. He took a steamer down the coast, past Korchula, Gruzh to Ragusa. There he hired a carriage and went inland.

The country through which he drove was so picturesque, it had the appearance of a stage set: high mountains, deep lakes, orchards and vineyards in the valleys, roses frothing over every wall and ledge. The woodlands were the clearest green laced with dark pines, the forest overseen by a majestic, snow-covered peak in the distance. He passed waterfalls that burst straight from the living rock, the limestone country cleft asunder as if by a giant's hand. Judas trees, fig trees, poplars, beech, wisteria vines were in wild abundance like an earthly paradise, and when he came at last to the small capital city he was reminded of a miniature Venice, all pale palaces and churches shimmering in the summer light.

The royal palace was constructed of gleaming white marble, its various levels and terraces spilling down a steep hillside amidst flowering shrubs and roses. But the marquis had no eye for the magnificent beauty of the setting or the splendor of the building.

All he could think of was seeing her again.

Guards stopped him at the entrance gates, but he insisted on seeing Gregory, speaking to the soldiers in a half dozen languages until they at last understood him and took him to a small sentry's lodge to wait.

When Gregory opened the door and saw him, he said, frowning, "I was hoping you'd forgotten her."

"But then, I was hoping she'd stay with me at Woodhill," the marquis replied, his voice chill. "So we were both wrong."

The captain came into the room enough to shut the door. "I can keep you away from her."

"Don't make this difficult," Hugh said, his gaze direct, challenging. "The British prime minister is more than willing to take a personal interest in my affairs."

Gregory minutely shifted his stance. "Why would he do that?"

"Because I'm his godson, which isn't so important," Hugh blandly remarked, "but he actually likes me as well and finds the old matter of my coercion intriguing." He tipped his head slightly toward the door. "So I suggest you tell the princess I'm here."

"What do you intend to do?"

The marquis held the captain's gaze for a long moment, a palpable tension in the air. "I'm not sure," he finally said.

She'd had time to compose herself after the initial shock of Gregory's announcement, and when she walked into the salon where the marquis waited, she was able to say, poised and unruffled, "You found me."

"Did you think I wouldn't?"

She shrugged, the flowered silk ruffle on her shoulder fluttering marginally. "It's been almost three years," she said, not mentioning his reputation for forgetting the females in his life.

"You're well hidden," he coolly replied.

"It was necessary." Only monumental self-control allowed her to speak as though he were a stranger when his presence filled the room, when his eyes burned with such fury, when she could still remember how it felt to be held in his arms.

"You didn't think I'd care that you kept my son from me?"

"Of course I did."

"But?" he sardonically murmured.

"You're not that naive, Crewe."

"No, I suppose I'm not," he softly agreed, thinking of all the British consul in Ragusa had told him. "Your husband's dead, I hear."

"Yes." It took effort to withstand the scorn in his gaze.

"Did you kill him?"

She didn't answer immediately. "I suppose in a way I did," she finally said, lifting her chin a fraction as if to ward off his disdain. "Did you come all this way to revile me?" she coolly asked, not willing to take on the role of villainess regardless of his perceptions. "If you did, I'll bid you pleasant journey back to England."

"What color is real?" he brusquely asked, gesturing at her pale hair.

"Does it really matter?" Tart, acrid words.

"I remember you differently, that's all," he softly said, his tone suddenly alteredkind, warm again, the voice she remembered from the days and nights at Woodhill. "I saw you had my necklace on in Paris."

She forced herself to an exterior calmness she was far from feeling, the husky intimacy of his voice triggering a flood of memory she'd tried to lock away forever. "I wear it often," she replied. Every day, she reflected, although she didn't tell him that, his gift her sustaining talisman in a lonely world not of her making.

"You should have written. At least when our son was born."

"I wanted to; I wanted more than that, but"she softly sighed"circumstances wouldn't permit it. I don't have a personal life, Hugh. You must know that."

"Nor have I since you left. I've missed you," he softly murmured. He stood very still, tall, dark, sinfully handsome just as she remembered, his words the fantasy she'd dreamed and wished would come to life.

"I didn't dare miss you. I wasn't allowed," she said with the faintest of smiles, thinking perhaps prayers were answered after all.

"Gregory."

Her smile broadened minutely. "He bolsters my sense of duty."

"While I've missed my son's baby years."

"Forgive me for that. But my life had to be sacrificed for this…" She lifted her hand in a brief sweeping motion that took in the broad vista of the city outside the windows. "And I thought you'd soon find other entertainments anyway," she gently added.

"Didyou find entertainments?" His voice took on a sudden harshness.

"I've been like a nun if you must know, while I expect you've been finding pleasure in your usual way." An unwished-for jealousy flared at the thought of his licentious prodigality. "Have you had any new children lately?" she murmured, the taint of insolence in her words.

The wordnun had abruptly absolved the tumult of his bitterness and spleen. "What would you do if I said I'm staying?"

"Answer my question," she said.

"None. No children, not one," he carefully enunciated, understanding invidious suspicion and mistrust. "I haven't made love to a woman since you left."

"I've heard differently." Her green eyes sparked.

"Then Gregory is lying," he said with silky malice.

"It wasn't Gregory."

"One of the other advisers who control your life then."

"I chose to come back; no one controls me."

"Then free will isn't an issue," he brusquely noted. "Do you love me?" His voice shouldn't have been so chill, he realized. "Do you love me?" he repeated, a softer appeal in his tone this time.

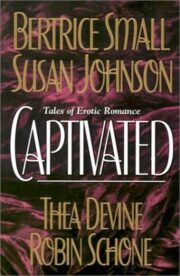

"Captivated" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Captivated". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Captivated" друзьям в соцсетях.