A few months later, Luca was on the road from Rome, riding east, wearing a plain working robe and cape of ruddy brown, and newly equipped with a horse of his own.

He was accompanied by his servant Freize, a broad-shouldered, square-faced youth, just out of his teens, who had plucked up his courage when Luca left their monastery, and volunteered to work for the young man, and follow him wherever the quest might take him. The abbot had been doubtful, but Freize had convinced him that his skills as a kitchen lad were so poor, and his love of adventure so strong, that he would serve God better by following a remarkable master on a secret quest ordained by the Pope himself, than by burning the bacon for the long-suffering monks. The abbot, secretly glad to lose the challenging young novice priest, thought the loss of an accident-prone spit lad was a small price to pay.

Freize rode a strong cob and led a donkey laden with their belongings. At the rear of the little procession was a surprise addition to their partnership: a clerk, Brother Peter, who had been ordered to travel with them at the last moment, to keep a record of their work.

‘A spy,’ Freize muttered out of the side of his mouth to his new master. ‘A spy if ever I saw one. Pale-faced, soft hands, trusting brown eyes: the shaved head of a monk and yet the clothes of a gentleman. A spy without a doubt.

‘Is he spying on me? No, for I don’t do anything and know nothing. Who is he spying on, then? Must be the young master, my little sparrow. For there is no-one else but the horses and they’re not heretics, nor pagans. They are the only honest beasts here.’

‘He is here to serve as my clerk,’ Luca replied irritably. ‘And I have to have him whether I need a clerk or no. So hold your tongue.’

‘Do I need a clerk?’ Freize asked himself as he reined in his horse. ‘No. For I do nothing and know nothing and, if I did, I wouldn’t write it down – not trusting words on a page. Also, not being able to read or write would likely prevent me.’

‘Fool,’ the clerk Peter said as he rode by.

‘“Fool,” he says,’ Freize remarked to his horse’s ears and to the gently climbing road before them. ‘Easy to say: hard to prove. And anyway, I have been called worse.’

They had been riding all day on a track little more than a narrow path for goats, which wound upwards out of the fertile valley, alongside little terraced slopes growing olives and vines, and then higher into the woodland where the huge beech trees were turning gold and bronze. At sunset, when the arching skies above them went rosy pink, the clerk drew a paper from the inner pocket of his jacket. ‘I was ordered to give you this at sunset,’ he said. ‘Forgive me if it is bad news. I don’t know what it says.’

‘Who gave it you?’ Luca asked. The seal on the back of the folded letter was shiny and smooth, unmarked with any crest.

‘The lord who hired me, the same lord who commands you,’ Peter said. ‘This is how your orders will come. He tells me a day and a time, or sometimes a destination, and I give you your orders then and there.’

‘Got them tucked away in your pocket all the time?’ Freize inquired.

Grandly, the clerk nodded.

‘Could always turn him upside down and shake him,’ Freize remarked quietly to his master.

‘We’ll do this as we are ordered to do it,’ Luca replied, looping the reins of his horse casually around his shoulder to leave his hands free to break the seal to open the folded paper. ‘It’s an instruction to go to the abbey of Lucretili,’ he said. ‘The abbey is set between two houses, a nunnery and a monastery. I am to investigate the nunnery. They are expecting us.’ He folded the letter and gave it back to Peter.

‘Does it say how to find them?’ Freize asked gloomily. ‘For otherwise it’s bed under the trees and nothing but cold bread for supper. Beechnuts, I suppose. All you could eat of beechnuts. You could go mad with gluttony on them. I suppose I might get lucky and find us a mushroom.’

‘The road is just up ahead,’ Peter interrupted. ‘The abbey is near to the castle. I should think we can claim hospitality at either monastery or nunnery.’

‘We’ll go to the convent,’ Luca ruled. ‘It says that they are expecting us.’

It did not look as if the convent was expecting anyone. It was growing dark, but there were no warm welcoming lights showing and no open doors. The shutters were closed at all the windows in the outer wall, and only narrow beams of flickering candlelight shone through the slats. In the darkness they could not tell how big it was; they just had a sense of great walls marching off either side of the wide-arched entrance gateway. A dim horn lantern was hung by the small door set in the great wooden gate, throwing a thin yellow light downward, and when Freize dismounted and hammered on the wooden gate with the handle of his dagger they could hear someone inside protesting at the noise and then opening a little spy hole in the door, to peer out at them.

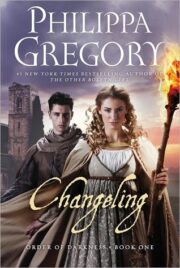

"Changeling" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Changeling". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Changeling" друзьям в соцсетях.