‘Discreet,’ Peter the clerk remarked.

‘Secretive,’ Freize said cheerfully. ‘Am I to stand outside and make sure no-one interrupts or eavesdrops?’

‘Yes.’ Luca pulled up a chair to the empty table and waited while Brother Peter produced papers, a black quill pen and a pot of ink, then seated himself at the end of the table, and looked at Luca expectantly. The three young men paused. Luca, overwhelmed with the task that lay before him, looked blankly back at the other two. Freize grinned at him, and made an encouraging gesture like someone waving a flag. ‘Onward!’ he said. ‘Things are so bad here, that we can’t make them worse.’

Luca choked on a boyish laugh. ‘I suppose so,’ he said, taking his seat, and turned to Brother Peter. ‘We’ll start with the Lady Almoner,’ he said, trying to speak decisively. ‘At least we know her name.’

Freize nodded and went to the door. ‘Fetch the Lady Almoner,’ he said to Sister Anna.

She came straight away, and took a seat opposite Luca. He tried not to look at the serene beauty of her face, her grey knowing eyes that seemed to smile at him with some private knowledge.

Formally, he took her name, her age – twenty-four – the name of her parents, and the duration of her stay in the abbey. She had been behind the abbey walls for twenty years, since her earliest childhood.

‘What do you think is happening here?’ Luca asked her, emboldened by his position as the inquirer, by his sense of his own self-importance, and by the trappings of his work: Freize at the door, and Brother Peter with his black quill pen.

She looked down at the plain wooden table. ‘I don’t know. There are strange occurrences, and my sisters are very troubled.’

‘What sort of occurrences?’

‘Some of my sisters have started to have visions, and two of them have been rising up in their sleep – getting out of their beds and walking though their eyes are still closed. One cannot eat the food that is served in the refectory, she is starving herself and cannot be persuaded to eat. And there are other things. Other manifestations.’

‘When did it start?’ Luca asked her.

She nodded wearily, as if she expected such a question. ‘It was about three months ago.’

‘Was that when the new Lady Abbess came?’

A breath of a sigh. ‘Yes. But I am convinced that she has nothing to do with it. I would not want to give evidence to an inquiry that was used against her. Our troubles started then – but you must remember she has no authority with the nuns, being so new, so inexperienced, having declared herself unwilling. A nunnery needs strong leadership, supervision, a woman who loves the life here. The new Lady Abbess lived a very sheltered life before she came to us, she was the favoured child of a great lord, the indulged daughter of a great house; she is not accustomed to command a religious house. She was not raised here. It is not surprising that she does not know how to command.’

‘Could the nuns be commanded to stop seeing visions? Is it within their choice? Has she failed them through her inability to command?’

Peter the clerk made a note of the question.

The Lady Almoner smiled. ‘Not if they are true visions from God,’ she said easily. ‘If they are true visions, then nothing would stop them. But if they are errors and folly, if they are women frightening themselves and allowing their fears to rule them . . . If they are women dreaming and making up stories . . . Forgive me for being so blunt, Brother Luca, but I have lived in this community for twenty years and I know that two hundred women living together can whip up a storm over nothing if they are allowed to do so.’

Luca raised his eyebrows. ‘They can invoke sleepwalking? They can invoke running out at night and trying to get out of the gates?’

She sighed. ‘You saw?’

‘Last night,’ he confirmed.

‘I am sure that there are one or two who are truly sleepwalkers. I am sure that one, perhaps two, have truly seen visions. But now I have dozens of young women who are hearing angels, and seeing the movement of stars, who are waking in the night and are shrieking out in pain. You must understand, Brother, not all of our novices are here because they have a calling. Very many are sent here by families who have too many children at home, or because the girl is too scholarly, or because she has lost her betrothed or cannot be married for some other reason. Sometimes they send us girls who are disobedient. Of course, they bring their troubles here, at first. Not everyone has a vocation, not everyone wants to be here. And once one young woman leaves her cell at night, against the rules, and runs around the cloisters, there is always someone who is going to join her.’ She paused. ‘And then another, and another.’

‘And the stigmata? The sign of the cross on her palms?’

He could see the shock in her face. ‘Who told you about that?’

‘I saw the girl myself, last night, and the other women who ran after her.’

She bowed her head and clasped her hands together; he thought for a moment that she was praying for guidance as to what she should say next. ‘Perhaps it is a miracle,’ she said quietly. ‘The stigmata. We cannot know for sure. Perhaps not. Perhaps – Our Lady defend us from evil – it is something worse.’

Luca leaned across the table to hear her. ‘Worse? What d’you mean?’

‘Sometimes a devout young woman will mark herself with the five wounds of Christ. Mark herself as an act of devotion. Sometimes young women will go too far.’ She took a nervous shuddering breath. ‘That is why we need strong discipline in the house. The nuns need to feel that they can be cared for, as a daughter is cared for by her father. They need to know that there are strict limits to their behaviour. They need to be carefully ruled.’

‘You fear that the women are harming themselves?’ Luca asked, shocked.

‘They are young women,’ the Lady Almoner repeated. ‘And they have no leadership. They become passionate, stirred up. It is not unknown for them to cut themselves, or each other.’

Brother Peter and Luca exchanged a horrified glance, Brother Peter ducked down his head and made a note.

‘The abbey is wealthy,’ Luca observed, speaking at random, to divert himself from his shock.

She shook her head. ‘No, we have a vow of poverty, each and every one of us. Poverty, obedience and chastity. We can own nothing, we cannot follow our own will, and we cannot love a man. We have all taken these vows; there is no escaping them. We have all taken them. We have all willingly consented.’

‘Except the Lady Abbess,’ Luca suggested. ‘I understand that she protested. She did not want to come. She was ordered to enter the abbey. She did not choose to be obedient, poor, and without the love of a man.’

‘You would have to ask her,’ the Lady Almoner said with quiet dignity. ‘She went through the service. She gave up her rich gowns from the great chests of clothes that she brought in with her. Out of respect for her position in the world she was allowed to change her gown in private. Her own servant shaved her head and helped her dress in coarse linen, and a wool robe of our order, with a wimple around her head and a veil on top of that. When she was ready she came into the chapel and lay alone on the stone floor before the altar, her arms spread out, her face to the cold floor, and she gave herself to God. Only she can know if she took the vows in her heart. Her mind is hidden from us, her sisters.’

She hesitated. ‘But her servant, of course, did not take the vows. She lives among us as an outsider. Her servant, as far as I know, follows no rules at all. I don’t know if she even obeys the Lady Abbess, or if their relationship is more . . .’

‘More what?’ Luca asked, horrified.

‘More unusual,’ she said.

‘Her servant? Is she a lay sister?’

‘I don’t know quite what you would call her. She was the Lady Abbess’s personal servant from childhood, and when the Lady Abbess joined us, the slave came too; she just accompanied her when she came, like a dog follows his master. She lives in the house of the Lady Abbess. She used to sleep in the storeroom next door to the Lady Abbess’s room, she wouldn’t sleep in the nun’s cells, then she started to sleep on the threshold of her room, like a slave. Recently she has taken to sleeping in the bed with her.’ She paused. ‘Like a bedmate.’ She hesitated. ‘I am not suggesting anything else,’ she said.

Brother Peter’s pen was suspended, his mouth open; but he said nothing.

‘She attends the church, following the Lady Abbess like her shadow; but she doesn’t say the prayers, nor confess, nor take Mass. I assume she is an infidel. I really don’t know. She is an exception to our rule. We don’t call her Sister, we call her Ishraq.’

‘Ishraq?’ Luca repeated the strange name.

‘She was born an Ottoman,’ the Lady Almoner said, her voice carefully controlled. ‘You will notice her around the abbey. She wears a dark robe like a Moorish woman, sometimes she holds a veil across her face. Her skin is the colour of caramel sugar, it is the same colour: all over. Naked, she is golden, like a woman made of toffee. The last lord brought her back with him as a baby from Jerusalem when he returned from the crusades. Perhaps he owned her as a trophy, perhaps as a pet. He did not change her name nor did he have her baptised; but had her brought up with his daughter as her personal slave.’

‘Do you think she could have had anything to do with the disturbances? Since they started when she came into the abbey? Since she came in with the Lady Abbess, at the same time?’

She shrugged. ‘Some of the nuns were afraid of her when they first saw her. She is a heretic, of course, and fierce-looking. She is always in the shadow of the Lady Abbess. They found her . . .’ She paused. ‘Disturbing,’ she said, then nodded at the word she had chosen. ‘She is disturbing. We would all say that: disturbing.’

‘What does she do?’

‘She does nothing for God,’ the Lady Almoner said with sudden passion. ‘For sure, she does nothing for the abbey. Wherever the Lady Abbess goes, she goes too. She never leaves her side.’

‘Surely she goes out? She is not enclosed?’

‘She never leaves the Lady Abbess’s side,’ she contradicted him. ‘And the Lady Abbess never goes out. The slave haunts the place. She walks in shadows, she stands in dark corners, she watches everything, and she speaks to none of us. It is as if we have trapped a strange animal. I feel as if I am keeping a tawny lioness, encaged.’

‘Are you afraid of her, yourself?’ Luca asked bluntly.

She raised her head and looked at him with her clear grey gaze. ‘I trust that God will protect me from all evil,’ she said. ‘But if I were not certain sure that I am under the hand of God she would be an utter terror to me.’

There was silence in the little room, as if a whisper of evil had passed among them. Luca felt the hairs on his neck prickle, while beneath the table Brother Peter felt for the crucifix that he wore at his belt.

‘Which of the nuns should I speak to first?’ Luca asked, breaking the silence. ‘Write down for me the names of those who have been walking in their sleep, showing stigmata, seeing visions, fasting.’

He pushed the paper and the quill before her and, without haste or hesitation, she wrote six names clearly, and returned the paper to him.

‘And you?’ he asked. ‘Have you seen visions, or walked in your sleep?’

Her smile at the younger man was almost alluring. ‘I wake in the night for the church services, and I go to my prayers,’ she said. ‘You won’t find me anywhere but warm in my bed.’

As Luca blinked that vision from his mind, she rose from the table and left the room.

‘Impressive woman,’ Peter said quietly, as the door shut behind her. ‘Think of her being in a nunnery from the age of four! If she’d been in the outside world, what might she have done?’

‘Silk petticoats,’ Freize remarked, inserting his broad head around the door from the hall outside. ‘Unusual.’

‘What? What?’ Luca demanded, furious for no reason, feeling his heart pound at the thought of the Lady Almoner sleeping in her chaste bed.

‘Unusual to find a nun in silk petticoats. Hair shirt, yes – that’s extreme perhaps, but traditional. Silk petticoats, no.’

‘How the Devil do you know that she wears silk petticoats?’ Peter demanded irritably. ‘And how dare you speak so, and of such a lady?’

‘Saw them drying in the laundry, wondered who they belonged to. Seemed an odd sort of garment for a nunnery vowed to poverty. Started to listen. I may be a fool but I can listen. Heard them whisper as she walked by me. She didn’t know I was listening, she walked by me as if I was a stone, a tree. Silk gives a little hss hss hss sound.’ He nodded smugly at Peter. ‘More than one way to make inquiry. Don’t have to be able to write to be able to think. Sometimes it helps to just listen.’

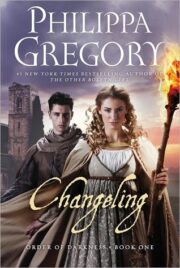

"Changeling" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Changeling". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Changeling" друзьям в соцсетях.