‘You have no brother or sister?’

‘I am alone in the world.’

‘You miss your parents?’

‘I do.’

‘You are lonely?’ The way he said it sounded like yet another accusation.

‘I suppose so. I feel very alone, if that is the same thing.’

The man rested the black feather of the quill against his lips in thought. ‘Your parents . . .’ He returned to the first question of the interrogation. ‘They were quite old when you were born?’

‘Yes,’ Luca said, surprised. ‘Yes.’

‘People talked at the time, I understand. That such an old couple should suddenly give birth to a son, and such a handsome son, who grew to be such an exceptionally clever boy?’

‘It’s a small village,’ Luca said defensively. ‘People have nothing to do but gossip.’

‘But clearly, you are handsome. Clearly, you are clever. And yet they did not brag about you, or show you off. They kept you quietly at home.’

‘We were close,’ Luca replied. ‘We were a close small family. We troubled nobody else, we lived quietly, the three of us.’

‘Then why did they give you to the Church? Was it that they thought you would be safer inside the Church? That you were specially gifted? That you needed the Church’s protection?’

Luca, still on his knees, shuffled in discomfort. ‘I don’t know. I was a child: I was only eleven. I don’t know what they were thinking.’

The Inquisitor waited.

‘They wanted me to have the education of a priest,’ he said eventually. ‘My father—’ He paused at the thought of his beloved father, of his grey hair and his hard grip, of his tenderness to his funny quirky little son. ‘My father was very proud that I learned to read, that I taught myself about numbers. He couldn’t write or read himself, he thought it was a great talent. Then, when some gypsies came through the village, I learned their language.’

The man made a note. ‘You can speak languages?’

‘People remarked that I learned to speak Romany in a day. My father thought that I had a gift, a God-given gift. It’s not so uncommon,’ he tried to explain. ‘Freize, the spit boy, is good with animals, he can do anything with horses, he can ride anything. My father thought that I had a gift like that, only for studying. He wanted me to be more than a farmer. He wanted me to do better.’

The Inquisitor sat back in his chair as if he was weary of listening, as if he had heard more than enough. ‘You can get up.’

He looked at the paper with its few black ink notes as Luca scrambled to his feet. ‘Now I will answer the questions that will be in your mind. I am the spiritual commander of an Order appointed by the Holy Father, the Pope himself, and I answer to him for our work. You need not know my name nor the name of the Order. We have been commanded by Pope Nicholas V to explore the mysteries, the heresies and the sins, to explain them where possible, and defeat them where we can. We are making a map of the fears of the world, travelling outwards from Rome to the very ends of Christendom to discover what people are saying, what they are fearing, what they are fighting. We have to know where the Devil is walking through the world. The Holy Father knows that we are approaching the end of days.’

‘The end of days?’

‘When Christ comes again to judge the living, the dead, and the undead. You will have heard that the Ottomans have taken Constantinople, the heart of the Byzantine empire, the centre of the Church in the east?’

Luca crossed himself. The fall of the eastern capital of the Church to an unbeatable army of heretics and infidels was the most terrible thing that could have happened, an unimaginable disaster.

‘Next, the forces of darkness will come against Rome, and if Rome falls it will be the end of days – the end of the world. Our task is to defend Christendom, to defend Rome – in this world, and in the unseen world beyond.’

‘The unseen world?’

‘It is all around us,’ the man said flatly. ‘I see it, perhaps as clearly as you see numbers. And every year, every day, it presses more closely. People come to me with stories of showers of blood, of a dog that can smell out the plague, of witchcraft, of lights in the sky, of water that is wine. The end of days approaches and there are hundreds of manifestations of good and evil, miracles and heresies. A young man like you can perhaps tell me which of these are true, and which are false, which are the work of God and which of the Devil.’ He rose from his great wooden chair and pushed a fresh sheet of paper across the table to Luca. ‘See this?’

Luca looked at the marks on the paper. It was the writing of heretics, the Moors’ way of numbering. Luca had been taught as a child that one stroke of the pen meant one: I, two strokes meant two: II, and so on. But these were strange rounded shapes. He had seen them before, but the merchants in his village and the almoner at the monastery stubbornly refused to use them, clinging to the old ways.

‘This means one: 1, this two: 2, and this three: 3,’ the man said, the black feather tip of his quill pointing to the marks. ‘Put the 1 here, in this column, it means one, but put it here and this blank beside it and it means ten, or put it here and two blanks beside it, it means one hundred.’

Luca gaped. ‘The position of the number shows its value?’

‘Just so.’ The man pointed the plume of the black feather to the shape of the blank, like an elongated O, which filled the columns. His arm stretched from the sleeve of his robe and Luca looked from the O to the white skin of the man’s inner wrist. Tattooed on the inside of his arm, so that it almost appeared engraved on skin, Luca could just make out the head and twisted tail of a dragon, a design in red ink of a dragon coiled around on itself.

‘This is not just a blank, it is not just an O, it is what they call a zero. Look at the position of it – that means something. What if it meant something of itself?’

‘Does it mean a space?’ Luca said, looking at the paper again. ‘Does it mean: nothing?’

‘It is a number like any other,’ the man told him. ‘They have made a number from nothing. So they can calculate to nothing, and beyond.’

‘Beyond? Beyond nothing?’

The man pointed to another number: –10. ‘That is beyond nothing. That is ten places beyond nothing, that is the numbering of absence,’ he said.

Luca, with his mind whirling, reached out for the paper. But the man quietly drew it back towards him and placed his broad hand over it, keeping it from Luca like a prize he would have to win. The sleeve fell down over his wrist again, hiding the tattoo. ‘You know how they got to that sign, the number zero?’ he asked.

Luca shook his head. ‘Who got to it?’

‘Arabs, Moors, Ottomans, call them what you will. Mussulmen, Muslim-men, infidels, our enemies, our new conquerors. Do you know how they got that sign?’

‘No.’

‘It is the shape left by a counter in the sand when you have taken the counter away. It is the symbol for nothing, it looks like a nothing. It is what it symbolises. That is how they think. That is what we have to learn from them.’

‘I don’t understand. What do we have to learn?’

‘To look, and look, and look. That is what they do. They look at everything, they think about everything, that is why they have seen stars in the sky that we have never seen. That is why they make physic from plants that we have never noticed.’ He pulled his hood closer, so that his face was completely shadowed. ‘That is why they will defeat us unless we learn to see like they see, to think like they think, to count like they count. Perhaps a young man like you can learn their language too.’

Luca could not take his eyes from the paper where the man had marked out ten spaces of counting, down to zero and then beyond.

‘So, what do you think?’ the Inquisitor asked him. ‘Do you think ten nothings are beings of the unseen world? Like ten invisible things? Ten ghosts? Ten angels?’

‘If you could calculate beyond nothing,’ Luca started, ‘you could show what you had lost. Say someone was a merchant, and his debt in one country, or on one voyage, was greater than his fortune, you could show exactly how much his debt was. You could show his loss. You could show how much less than nothing he had, how much he would have to earn before he had something again.’

‘Yes,’ the man said. ‘With zero you can measure what is not there. The Ottomans took Constantinople and our empire in the east not only because they had the strongest armies and the best commanders, but because they had a weapon that we did not have: a cannon so massive that it took sixty oxen to pull it into place. They have knowledge of things that we don’t understand. The reason that I sent for you, the reason that you were expelled from your monastery but not punished there for disobedience or tortured for heresy, is that I want you to learn these mysteries; I want you to explore them, so that we can know them, and arm ourselves against them.’

‘Is zero one of the things I must study? Will I go to the Ottomans and learn from them? Will I learn about their studies?’

The man laughed and pushed the piece of paper with the Arabic numerals towards the novice priest, holding it with one finger on the page. ‘I will let you have this,’ he promised. ‘It can be your reward when you have worked to my satisfaction and set out on your mission. And yes, perhaps you will go to the infidel and live among them and learn their ways. But for now, you have to swear obedience to me and to our Order. I will send you out to be my ears and eyes. I will send you to hunt for mysteries, to find knowledge. I will send you to map fears, to seek darkness in all its shapes and forms. I will send you out to understand things, to be part of our Order that seeks to understand everything.’

He could see Luca’s face light up at the thought of a life devoted to inquiry. But then the young man hesitated. ‘I won’t know what to do,’ Luca confessed. ‘I wouldn’t know where to begin. I understand nothing! How will I know where to go or what to do?’

‘I am going to send you to be trained. I will send you to study with masters. They will teach you the law, and what powers you have to convene a court or an inquiry. You will learn what to look for and how to question someone. You will understand when someone must be released to earthly powers – the mayors of towns or the lords of the manor; or when they can be punished by the Church. You will learn when to forgive and when to punish. When you are ready, when you have been trained, I will send you on your first mission.’

Luca nodded.

‘You will be trained for some months and then I shall send you out into the world with my orders,’ the man said. ‘You will go where I command and study what you find there. You will report to me. You may judge and punish where you find wrong-doing. You may exorcise devils and unclean spirits. You may learn. You may question everything, all the time. But you will serve God and me, as I tell you. You will be obedient to me and to the Order. And you will walk in the unseen world and look at unseen things, and question them.’

There was a silence. ‘You can go,’ the man said, as if he had given the simplest of instructions. Luca started from his silent attention and went to the door. As his hand was on the bronze handle the man said: ‘One thing more . . .’

Luca turned.

‘They said you were a changeling, didn’t they?’ The accusation dropped into the room like a sudden shower of ice. ‘The people of the village? When they gossiped about you being born, so handsome and so clever, to a woman who had been barren all her life, to a man who could neither read nor write. They said you were a changeling, left on her doorstep by the faeries, didn’t they?’

There was a cold silence. Luca’s stern young face revealed nothing. ‘I have never answered such a question, and I hope that I never do. I don’t know what they said about us,’ he said harshly. ‘They were ignorant fearful country people. My mother said to pay no attention to the things they said. She said that she was my mother and that she loved me above all else. That’s all that mattered, not stories about faerie children.’

The man laughed shortly and waved Luca to go, and watched as the door closed beind him. ‘Perhaps I am sending out a changeling to map fear itself,’ he said to himself, as he tidied the papers together and pushed back his chair. ‘What a joke for the worlds seen and unseen! A faerie child in the Order. A faerie child to map fear.’

THE CASTLE OF LUCRETILI, JUNE 1453

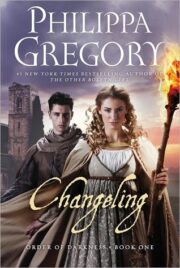

"Changeling" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Changeling". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Changeling" друзьям в соцсетях.