Freize tried to cheer the cook by explaining that it would all be over one way or another by tonight and that she would have to provide only one great dinner for this unique assembly of great men.

‘Never have I had so many lords in the house at any one time,’ she fretted. ‘I will have to send out for chickens and Jonas will have to let me have the pig that he killed last week.’

‘I’ll serve the dinner, and help you in the kitchen too,’ Freize promised her. ‘I’ll take the dishes up and put them before the gentry. I’ll announce each course and make it sound tremendous.’

‘The Lord knows that all you do is eat, and steal food for that animal in the yard. It’s causing more trouble to me out there than ever it did in the forest.’

‘Should we let it go, d’you think?’ Freize asked playfully.

She crossed herself. ‘Saints save us, no! Not after it took poor Mrs Fairley’s own child and she never recovered from the grief. And last week a lamb, and the week before that a hen right out of the yard. No, the sooner it’s dead the better. And your master had better order it killed or there will be a riot here. You can tell him that, from me. There are men coming into the village, shepherds from the highest farms, who won’t take kindly to a stranger who comes here and says that our werewolf should be spared. Your master should know that there can only be one ending here: the beast must die.’

‘Can I take that ham bone for it?’ Freize asked.

‘Isn’t that the very thing that was going to make soup for the bishop’s dinner?’

‘There’s nothing on it,’ Freize urged her. ‘Give it to me for the beast. You’ll get another bone anyway when Jonas butchers the pig.’

‘Take it, take it,’ she said impatiently. ‘And leave me to get on.’

‘I shall come and help as soon as I have fed the beast,’ Freize promised her.

She waved him out of the kitchen door into the yard and Freize climbed the platform and looked over the arena wall. The beast was lying down, but when it saw Freize it raised its head and watched him.

Freize vaulted to the top of the wall, swung his long legs over, and sat in comfort there, his legs dangling into the bear pit. ‘Now then,’ he said gently. ‘Good morning to you, beast. I hope you are well this morning?’

The beast came a little closer, to the very centre of the pit, and looked up at Freize. Freize leaned into the pit, holding tightly on to the wall with one hand, leaned down so far that the ham bone was dangling just below his feet. ‘Come,’ he said gently. ‘Come and get this. You have no idea what trouble it cost me to get it for you, but I saw the ham carved off it last night and I set my heart on it for you.’

The beast turned its head a little one way and then the other, as if trying to understand the string of words. Clearly, it understood the gentle tone of voice, as it yearned upwards to the silhouette of Freize, on the wall of the bear pit. ‘Come on,’ said Freize. ‘It’s good.’

Cautious as a cat, the beast approached on all fours. It came to the wall of the arena and sat directly under Freize’s feet. Freize stretched down to it and slowly the beast uncurled, put its front paws on the walls of the arena and reached up. It stood tall, perhaps more than four feet. Freize fought the temptation to shrink back from it, imagining it would sense his fear; but also he was driven on to see if he could feed this animal by hand, to see if he could bridge the divide between this beast and man. And he was driven, as always, by his own love of the dumb, the vulnerable, the hurt. He stretched down a little lower and the beast stretched up its shaggy head and gently took the ham bone in its mouth, as if it had been fed by a loving hand, all its life.

The moment it had the meat in its strong jaws, it sprang back from Freize, dropped to all fours and scuttled to the other side of the bear pit. Freize straightened up – and found Ishraq’s dark eyes on him.

‘Why feed it if I am to shoot it tonight?’ she asked quietly. ‘Why be kind to it, if it is nothing but a dead beast waiting for the arrow?’

‘Perhaps you won’t have to shoot it tonight,’ Freize answered. ‘Perhaps the little lord will find that it’s a beast we don’t know, or some poor creature that was lost from a fair. Perhaps he will rule that it’s an oddity, but not a limb of Satan. Perhaps he will say it is a changeling, put among us by strange people. Surely it is more like an ape than a wolf? What sort of a beast is it? Have you, in all your travels, in all your study, seen such a beast before?’

She looked uncertain. ‘No, never. The bishop is talking with your lord now. They are going through all sorts of books and papers to judge what should be done, how it should be tried and tested, how it should be killed, and how it should be buried. The bishop has brought in all sorts of scholars with him who say they know what should be done.’ She paused. ‘If it can speak like a Christian, then that alters everything. Your lord, Luca Vero, should be told.’

Freize’s glance never wavered. ‘Why would you think it could speak?’ he said.

She met his gaze without coquetry. ‘You’re not the only one who takes an interest in it,’ she said.

All day Luca was closeted with the bishop, his priests, and his scholars, the dining table spread with papers which recorded judgements against werewolves and the histories of wolves going back to the very earliest times: records from the Greek philosophers’ accounts, translated by the Arabs into Arabic and then translated back again into Latin. ‘So God knows what they were saying in the first place,’ Luca confided in Brother Peter. ‘There are a dozen prejudices that the words have to get through, there are half a dozen scholars for every single account, and they all have a different opinion.’

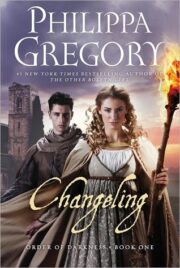

"Changeling" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Changeling". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Changeling" друзьям в соцсетях.