The little tap came again, and she put back the richly embroidered covers of her bed and went to the door, the key in her hand. ‘Who is it?’

‘It is Prince Roberto. I have to speak with you.’

‘I can’t open the door, I will speak with you tomorrow.’

‘I need to speak to you tonight. It is about the will, your father’s wishes.’

She hesitated. ‘Tomorrow . . .’

‘I think I can see a way out for you. I understand how you feel, I think I can help.’

‘What way out?’

‘I can’t shout it through the door. Just open the door a crack so that I can whisper.’

‘Just a crack,’ she said, and turned the key, keeping her foot pressed against the bottom of the door to ensure that it opened only a little.

As soon as he heard the key turn, the prince banged the door open with such force that it hit Isolde’s head and sent her reeling back into the room. He slammed the door behind him and turned the key, locking them in together.

‘You thought you would reject me?’ he demanded furiously, as she scrambled to her feet. ‘You thought you – practically penniless – would reject me? You thought I would beg to speak to you through a closed door?’

‘How dare you force your way in here?’ Isolde demanded, white-faced and furious. ‘My brother would kill you—’

‘Your brother allowed it,’ he laughed. ‘Your brother approves me as your husband. He himself suggested that I come to you. Now get on the bed.’

‘My brother?’ She could feel her shock turning into horror as she realised that she had been betrayed by her own brother, and that now this stranger was coming towards her, his fat face creased in a confident smile.

‘He said I might as well take you now as later,’ he said. ‘You can fight me if you like. It makes no difference to me. I like a fight. I like a woman of spirit, they are more obedient in the end.’

‘You are mad,’ she said with certainty.

‘Whatever you like. But I consider you my betrothed wife, and we are going to consummate our betrothal right now, so you don’t make any mistake tomorrow.’

‘You’re drunk,’ she said, smelling the sour stink of wine on his breath.

‘Yes, thank God, and you can get used to that too.’

He came towards her, shrugging his jacket off his fleshy shoulders. She shrank back until she felt the tall wooden pole of the four-poster bed behind her, blocking her retreat. She put her hands behind her back so that he could not grab them, and felt the velvet of the counterpane, and beneath it the handle of the brass warming pan filled with hot embers that had been pushed between the cold sheets.

‘Please,’ she said. ‘This is ridiculous. It is an offence against hospitality. You are our guest, my father’s body lies in the chapel. I am without defence, and you are drunk on our wine. Please go to your room and I will speak kindly to you in the morning.’

‘No,’ he leered. ‘I don’t think so. I think I shall spend the night here in your bed and I am very sure you will speak kindly to me in the morning.’

Behind her back, Isolde’s fingers closed on the handle of the warming pan. As Roberto paused to untie the laces on the front of his breeches, she got a sickening glimpse of grey linen poking out. He reached for her arm. ‘This need not hurt you,’ he said. ‘You might even enjoy it . . .’

With a great swing she brought the warming pan round to clap him on the side of his head. Red-hot embers and ash dashed against his face and tumbled to the floor. He let out of a howl of pain as she drew back and hit him once again, hard, and he dropped down like a fat stunned ox before the slaughter.

She picked up a jug and flung water over the coals smouldering on the rug beneath him and then, cautiously, she kicked him gently with her slippered foot. He did not stir, he was knocked out cold. Isolde went to an inner room and unlocked the door, whispering ‘Ishraq!’ When the girl came, rubbing sleep from her eyes, Isolde showed her the man crumpled on the ground.

‘Is he dead?’ the girl asked calmly.

‘No. I don’t think so. Help me get him out of here.’

The two young women pulled the rug and the limp body of Prince Roberto slid along the floor, leaving a slimy trail of water and ashes. They got him into the gallery outside her room and paused.

‘I take it your brother allowed him to come to you?’

Isolde nodded, and Ishraq turned her head and spat contemptuously on the prince’s white face. ‘Why ever did you open the door?’

‘I thought he would help me. He said he had an idea to help me then he pushed his way in.’

‘Did he hurt you?’ The girl’s dark eyes scanned her friend’s face. ‘Your forehead?’

‘He knocked me when he pushed the door.’

‘Was he going to rape you?’

Isolde nodded.

‘Then let’s leave him here,’ Ishraq decided. ‘He can come to on the floor like the dog that he is, and crawl to his room. If he’s still here in the morning then the servants can find him and make him a laughing-stock.’ She bent down and felt for his pulses at his throat, his wrists and under the bulging waistband of his breeches. ‘He’ll live,’ she said certainly. ‘Though he wouldn’t be missed if we quietly cut his throat.’

‘Of course we can’t do that,’ Isolde said shakily.

They left him there, laid out like a beached whale on his back, with his breeches still unlaced.

‘Wait here,’ Ishraq said and went back to her room.

She returned swiftly, with a small box in her hand. Delicately, using the tips of her fingers and scowling with distaste, she pulled at the prince’s breeches so that they were gaping wide open. She lifted his linen shirt so that his limp nakedness was clearly visible. She took the lid from the box and shook the spice onto his bare skin.

‘What are you doing?’ Isolde whispered.

‘It’s a dried pepper, very strong. He is going to itch like he has the pox, and his skin is going to blister like he has a rash. He is going to regret this night’s work very much. He is going to be itching and scratching and bleeding for a month, and he won’t trouble another woman for a while.’

Isolde laughed and put out her hand, as her father would have done, and the two young women clasped forearms, hand to elbow, like knights. Ishraq grinned, and they turned and went back into the bedroom, closing the door on the humbled prince and locking it firmly against him.

In the morning, when Isolde went to chapel, her father’s coffin was closed and ready for burial in the deep family vault – and the prince was gone.

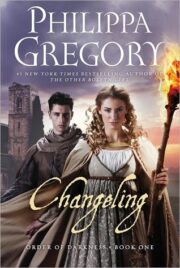

"Changeling" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Changeling". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Changeling" друзьям в соцсетях.