This missive he gave to Aldham on the following morning, telling him to send it by express post to Inglehurst. He then climbed into his chaise, and set forward on the long journey into Yorkshire.

Chapter 9

The Viscount suffered no delays on his journey, and might have reached Harrowgate at the end of the second day had it not occurred to him that to arrive without warning at a watering-place in the height of its season would probably entail a prolonged search for accommodation, and that the late evening was scarcely the time to prosecute this. So he spent the second night at the King’s Arms, in Leeds, leaving himself with only some twenty more miles to cover. He was an extremely healthy young man, and since he spent a great part of his time in all the more energetic forms of sport it was hard to tire him out, but two very long days in a post-chaise had made him feel as weary as he was bored. The chaise was his own, and very well-sprung, but it was also very lightly built, which, while it made for speed, meant that it bounded over the inequalities of the road in a manner not at all conducive to repose. Midway through the second day he remarked to Tain that he wished he could exchange places with one of the post-boys. Quite shocked, Tain said incredulously: “Exchange places with a post-boy, my lord?”

“Yes, for he at least has something to do. Though I daresay I shouldn’t care to be obliged to wear a leg-iron,” he added reflectively.

“No, my lord,” said Tain, primly. “Certainly not! A very unbecoming thing for any gentleman to do!”

“Also uncomfortable, don’t you think?” suggested Desford, gently quizzing him.

“I have never worn one, my lord, so I cannot take it upon myself to venture an opinion,” replied Tain, in chilly accents.

“I must remember to ask my own wheel-boy,” said Desford provocatively.

But Tain, refusing to be drawn, merely said; “Certainly, my lord,” leaving Desford to regret that it was he and not Stebbing who was sitting beside him. Stebbing would undoubtedly have entered with enthusiasm into a discussion, embellishing it with some entertaining anecdotes illustrative of the advantages and disadvantages attached to a postilion’s career.

However, the regret vanished when the Viscount remembered how valuable Tain’s services became from the instant that he climbed down from the chaise, and entered whatever posting-house his employer had chosen to honour with his patronage on this or any other journey. In some mysterious way known only to himself he could transform the most unpromising bedchamber into an inviting one in no more than a flea’s leap, as the saying was; to lay out a change of raiment for his master; to make such arrangements for his comfort as Desford would not have thought it necessary to command, if left to manage for himself; to press out the creases in his coat; to launder his neckcloth and his shirt; to procure extra candles; and to overawe the domestic staff into bringing up hot water to my lord’s room without delay as soon as he himself demanded it. Stebbing might be a more amusing companion during a tedious journey, but none of Tain’s arts was known to him, as the Viscount realized, and acknowledged, when, as Tain drew the curtains round his bed that evening, he murmured: “Thank you! I only wish you may have ensured your own comfort half as well as you have ensured mine!”

He did not reach Harrowgate until shortly before noon on the following morning, because although he had had the intention of setting forward on the last few miles of his journey at eight o’clock Tain had quite deliberately refrained from rousing him until an hour later, saying mendaciously, but with complete sangfroid, that he had misunderstood his instructions. What he did not say was that when he had softly entered the room at six o’clock he had found the Viscount sunk in a profound sleep from which he had not had the heart to rouse him. He guessed, judging by his own experience, that my lord had spent the first part of the night under the lingering impression that he was still bowling and bounding and swaying over the road, and had only slept in uneasy snatches until overcome by exhaustion. As this guess was correct, and Desford was still feeling both sleepy and battered, the excuse was received with a prodigious yawn, accompanied by nothing more alarming than a sceptical glance, and a rather thickly uttered: “Oh, well—!”

Revived by an excellent breakfast, Desford shook off his unaccustomed lassitude, and resumed his journey. It was a day of bright sunshine, with just enough wind blowing off the moors to make it invigorating, and under these conditions he saw Harrowgate at its best, and was much inclined to think that his anonymous Guide had maligned the place. The Low Town did not attract him, but the situation of High Harrowgate, which lay nearly a mile beyond it, was as pleasant as the Guide had grudgingly described. On a clear day—and this was a very clear day—York Minster could be seen in the distance, with the Hambleton hills beyond; and to the west the mountains of Craven. Besides the race course, the theatre, and the principal Chalybeate, High Harrowgate possessed a large green, which was one of its most agreeable features, and round which three of its chief hotels stood, a great many shops, and what bore all the appearance of being a fashionable library. “Come now!” exclaimed Desford cheerfully, as the chaise drew up at the Dragon. “I don’t consider this a dreary place at all, do you, Tain?”

“Your lordship has not yet seen it in bad weather,” responded Tain unencouragingly. “I should not myself choose to sojourn here on a dull day, when the prospect would no doubt be shrouded in mist.”

Neither the Dragon nor the Granby had a room to spare, but the Viscount was more fortunate at the Queen’s, where, after a hurried colloquy with his spouse, conducted in an urgent whisper, the landlord was happy to inform his lordship that he had just one room vacant—indeed, one of his best rooms, looking out on to the green, which he was only able to offer because the gentleman who had booked it had unaccountably failed to honour his contract. He then escorted Desford upstairs to inspect it, and, on its being approved, bowed himself out, and hurried downstairs again, first to order a couple of menials to carry up the gentleman’s baggage to No. 7, and then to inform his flustered wife that if Mr Fritwell should happen to show his front Jack (the hope of his house) would have to give up his room to him, and bed down over the stables. Upon her venturing to expostulate he silenced her by saying that if she thought he was going to turn away a well-breeched swell, travelling in a chaise-and-four, and attended by his valet, merely to avoid offending old Mr Fritwell, who was more inclined to argue over the reckoning than to drop his blunt freely, she was the more mistaken.

Little though he knew it, the Viscount was indebted to Tain’s entrance upon the scene, bearing his dressing-case, for the landlord’s decision to sacrifice old Mr Fritwell. The landlord was sharp enough to recognize after one look at his lordship that a member of the Quality had walked into the inn, and—after a second, shrewd, glance at the cut of his lordship’s coat, the intricate folds of his neckcloth, and the gloss on his top-boots—no country squire, but a London buck of the first head; but it was Tain’s arrival which clinched the matter. Unknown ladies and gentlemen travelling without their personal servants found it hard to obtain accommodation at any of the best inns in Harrowgate, valets and abigails apparently being regarded by the landlords as insurances against the possibility of being choused out of their due reckonings.

The Viscount had not thought it necessary to acquaint the landlord either with his name or his rank, but this was a foolish omission speedily rectified by Tain, far better versed in such matters than his master. Instead of following immediately in the Viscount’s wake, he awaited the landlord’s return at the foot of the stairs, and proceeded with quelling civility to make known to him my lord’s requirements. By the time he had reached the stage of warning the landlord not, on any account, to permit the Boots to lay a finger on my lord’s footwear, he had succeeded in so much enlarging his master’s consequence that it would not have been surprising if the landlord had believed himself to be entertaining, if not a Royal prince, at least a Serene Highness.

As a result of these competent, if top-lofty, tactics, he was able to inform the Viscount, when he presently rejoined him in No. 7, that he had ventured to bespeak a private parlour for him, and to arrange with the landlord for his dinner to be served there. The Viscount, who was standing by the window, watching the various persons passing below, replied absently: “Have you? I thought it not worth while to ask for one since I don’t expect to be here above a couple of nights, but I daresay you’re right. You know, Tain, the place is full of valetudinarians! I’ve never seen so many people hobbling along on sticks in my life!”

“Exactly so, my lord!” said Tain, beginning swiftly to unpack the contents of the dressing-case. “I have myself seen three of them enter this house, one of them being an elderly lady of what one must call a garrulous disposition. I formed the opinion that if she were to subject your lordship to a description of her sufferings and of the cure which she is undergoing you would be hard put to it to maintain even the appearance of civility.”

“Then you were certainly right to procure a private parlour for me,” said the Viscount, laughing.

Leaving Tain to unpack his portmanteau, he sallied forth to continue his search for Lord Nettlecombe. He had already enquired for him at the Dragon and the Granby, without meeting with anything but blank looks and head-shakings, so, as the Chalybeate, under its imposing dome, lay on the opposite side of the green he thought he might as well make that his first port of call. If Lord Nettlecombe had come to Harrowgate for his health’s sake it seemed likely that he must by now have become a familiar figure there. But none of the attendants seemed to have heard of his lordship, the most helpful amongst them being unable to do more than suggest that he should be sought at the Tewit Well, which was the second of the two Chalybeates, situated half-a-mile to the west of the principal one.

Desford strode off, glad to be able to stretch his legs after having been cooped up for so many hours, but although he enjoyed a brisk walk it ended in another rebuff, accompanied by a recommendation to try the Sulphur Wells, at Lower Harrowgate, and the information that although the Lower town was a mile distant by road it was no more than half-a-mile away if approached “over the stile”. But as the directions given to him on how to reach the stile were as vague as such directions too often are, Desford decided to enquire at the inns and boarding-houses in High Harrowgate, before extending his search to the Lower town.

He very soon discovered that although Harrowgate was described by the Guide as consisting of two scattered villages this was another of that anonymous author’s misleading statements: no village that Desford had yet seen contained so many inns and boarding-houses as High Harrowgate. At none of those he visited was he able to obtain any news of his quarry, and by the time a church clock struck the hour of six, at which unfashionable time dinner was served at all the best inns, he was tired, hungry, and exasperated, and thankfully abandoned, for that day, his fruitless search.

When he reached the Queen he was considerably surprised by the respect with which he was greeted, the porter bowing him in, a waiter hurrying forward to discover whether he would take a glass of sherry before he went upstairs to his parlour, and the landlord breaking off a conversation with a less favoured guest to conduct him to the stairs, informing him on the way that dinner—which he trusted would meet with his approval—should be served immediately, and that he had taken it upon himself to bring up a bottle of his best burgundy from the cellar, and one of a very tolerable claret, in case my lord should prefer the lighter wine.

The reason for these embarrassingly obsequious attentions was soon made plain to the Viscount. Tain, relieving him of his hat and gloves, said that he had ventured to order a neat, plain dinner for him, consisting of a Cressy soup, removed with a fillet of veal, some glazed sweetbreads, and a few petit pates, to be followed by a second course of which prawns, peas, and a gooseberry tart were the principal dishes. “I took the precaution, my lord,” he said, “of looking at the bill of fare, and saw that it was just as I had feared: a mere ordinary, and not at all what you are accustomed to. So I ordered what I believe you will like.”

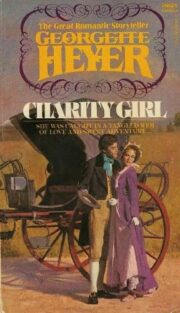

"Charity Girl" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Charity Girl". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Charity Girl" друзьям в соцсетях.