“That’s what I’ve come to do,” said the Viscount. “And since I’ve no more liking for beating about the bush than you have, sir, I’ll tell you at once that I’ve driven over from Inglehurst, where I learned of your visit there.”

“I thought as much!” said the Earl. “Come to beg me to help you out of this scrape you’ve got yourself into, have you?”

“No, nothing of that sort,” responded Desford. “Merely to give you a round tale, which—since I understand you learned by way of the backstairs of Cherry Steane’s presence at Inglehurst, and that it was I who took her there—I’m tolerably certain you haven’t yet heard.”

“I’m well aware of that!” said his father, his eyes kindling. “And before you say any more, Desford, let me tell you that I set no store by servants’ gossip—least of all when it concerns any of my sons!”

The Viscount smiled at him. “Of course you don’t, sir. But it did send you to Inglehurst to discover what I had been doing to give rise to such gossip, didn’t it? I don’t blame you: it must have seemed to you that I was up to my chin in some devilish havey-cavey doings. Hetta could have told you why I placed Cherry in her care, but she says you didn’t ask her any questions at all.”

“Do you imagine that I would ask her, or anyone else, prying questions about my sons?” demanded the Earl, bristling. “Upon my word, Desford, if that’s the opinion you hold of me you have gone your length!”

“I know you far too well, Papa, to hold any such opinion,” replied the Viscount imperturbably. “For which reason I’ve thought it best to open the whole budget to you myself.”

“Then cut line and do sol” commanded his father sternly.

Thus encouraged, Desford disclosed to him, in unvarnished terms, the history of the past two weeks. The Earl listened to him in silence, and with a frown drawing his brows together over his hard, piercing eyes. It did not relax when the Viscount came to the end of his recital, but all he said was: “In the briars, aren’t you?”

“I may be in the briars,” retorted Desford, “but I’m not at Point Non-Plus, sir, believe me!”

The Earl grunted, “What do you mean to do if this school-dame you talk about don’t come up to scratch?”

“Try a fresh cast!”

The Earl grunted again, and his frown deepened. After a long pause, during which he bore all the appearance of being engaged in a struggle with himself, he said, as though the words were being forced out of him: “You’re of age, you’re independent of me, you can please yourself, but—I beg of you, Desford, don’t think yourself obliged, in honour, to marry the girl!”

The Viscount said gently: “I don’t think it, sir, for I have in no way compromised her. But I do think that I am bound, in honour, to befriend her.”

His father nodded, but said, in sudden exasperation: “I wish to God you had left Sophronia’s house an hour earlier!”

“Well,” said Desford, with a twisted smile, “between ourselves, sir, so do I! At least—No, I don’t wish it, when I think of what might have befallen that pretty, foolish child if I hadn’t overtaken her on the road. But I certainly wish I hadn’t accepted my aunt’s invitation to stay at Hazelfield!”

“No good ever yet came from crying over spilt milk, so we’ll leave that! You’ve got yourself into a rare bumble-bath, but it might have been worse.” He pulled his snuff-box out of his pocket, and helped himself to a pinch. He then said abruptly: “I’ve met the girl. I don’t scruple to own to you that I went over to Inglehurst for that purpose, and I’m glad I did, for I saw at a glance that she isn’t the sort of highflyer you dangle after.”

Desford laughed. “Pray, sir, how do you know what sort of highflyers I dangle after?”

“I know more than you think, my boy!” said his lordship, grimly pleased with himself. “When I first heard of this business, I was afraid you’d lost your head over the girl, and meant to become riveted to her. You wouldn’t have taken a lightskirt to the Silverdales. And if you were meaning to become a tenant-for-life you wouldn’t have brought her here, for you know well I’d do my utmost to prevent your marrying into that family! Another possibility was that she’d snared you—Yes, yes, I know you’ve plenty of rumgumption, but wiser men than you have been trapped by designing females! To tell you the truth, I was prepared to buy her off, but I cut my wisdoms before you were born, and it didn’t take me more than a couple of minutes to realize that she was nothing but a schoolroom miss—pretty enough, but not your style of female, and damned shy into the bargain! So now, Desford, perhaps you’ll have the goodness to tell me why you didn’t bring her here, instead of planting her on Lady Silverdale?”

The Viscount, who had foreseen that this question would sooner or later be shot at him, flung up a hand, in the gesture of a fencer acknowledging a hit, and said, with a comical look of guilt: “Peccavi, Papa! I didn’t dare to!”

His father gave a crack of laughter, which he instantly suppressed, saying: “I suppose I must consider it some comfort that in spite of your faults you are at least honest! I collect you dared not bring her here for fear that I might be so lost to all sense of propriety as to have driven the pair of you out of the house. Much obliged to you, Desford!”

“Papa, how can you rip up at me so unkindly?” said Desford reproachfully. “I thought nothing of the sort—as well you know!—but I did think that it would make you as cross as crabs if I saddled you and Mama with Wilfred Steane’s daughter. If you tell me that I was wrong, I have nothing to do but to beg your pardon for having so wickedly misjudged you—but was I wrong, sir?”

The Earl eyed him in fulminating silence for several minutes, but at last replied, in the voice of one driven into the last ditch: “No, damn you!”

“If I’m honest,” said Desford, smiling at him, “it’s an inherited virtue, sir!”

“Mawworm!” said his lordship, concealing under this opprobrious word his gratification. “Don’t think you can flummery me!”He then palliated his severity by saying, after a reflective moment: “Well, well, I don’t mean to pinch at you, so we’ll say no more on that head! All I will say is that if you find yourself at the end of your rope over this business come to me! I may be outdated, and gout-ridden, but I still know one point more than the devil!”

“Several points more than the devil, sir!” said Desford. “I should most certainly come to you if I reached the end of my rope.”

His lordship nodded, apparently satisfied, for the next thing he said was: “To think of old Nettlecombe’s having fallen into parson’s mousetrap at his time of life! Did you say that he’d married his housekeeper?”

Thus it came about that when Lady Wroxton entered the library half-an-hour later she found father and son on the best of good terms. Indeed, the first sound she heard when she opened the door was a shout of laughter from Desford, to whom his father was describing, in highly coloured terms, what had been his own experiences in Harrowgate. She was not very much surprised; for she had considerable faith in Desford’s ability to deal with his father, and she knew that however violently her lord might deny the imputation, Desford was the son nearest to his heart.

My lord greeted her genially, saying: “Ah, here you are, my lady! Now, come in, and tell Desford if I wasn’t poisoned by those stinking waters at Harrowgate!”

“Well, they certainly made you extremely sick,” she said. “But you only drank a very small quantity, you know, and there’s no saying that they wouldn’t have done you good if only we could have prevailed upon you to persevere.” As she spoke, she warmly embraced Desford, who had risen at her entrance, and had crossed the floor towards her, to put his arms round her in a breath-taking hug. She kissed him, but pinched his chin as well, saying, as she looked lovingly up into his handsome face: “So now you’ve turned into a knight-errant, I hear! What next will you do, dearest?”

He laughed, but my lord said that he forbade her to give the boy a scold. “He has made a clean breast of the affair to me, my love, and I have said all that was necessary, so there’s an end to it! No one,” he added, with absolute conviction, “can say that I am one to ride grub!”

“No, my dear,” she said gravely, but with Desford’s smile lurking in her eyes. She let Desford lead her to a chair, and gave his hand a little squeeze before she let it go, and said: “I had a comfortable cose with Hetta, Ashley, and I collect, from what she told me, that your protégée is a very amiable and well-conducted girl, which, I own, surprised me, and makes me think her mama must have had more delicacy of principle than one would have supposed—recalling the circumstances of her marriage—for Wilfred Steane had no principles at all. It seems that Lady Silverdale has taken a great fancy to her, and is much inclined to invite her to stay at Inglehurst, but Hetta thinks it will not answer.”

“I know she does, ma’am, and I agree with her.”

“A pity,” she said, in her calm way. “However, I daresay Hetta is right. So what do you mean to do with the poor little creature?”

He told her what his plan was, and she accepted it, merely saying that if any other recommendation of Cherry to a possible employer than Miss Fletching’s was needed, she would be very happy to supply it. After that no more was said on the subject, my lord demanding to know what she thought of old Nettlecombe’s being trapped into marriage by his housekeeper, and bidding Desford tell her all about his Harrowgate adventures.

Nothing occurred to mar the harmony of the evening, and when his lordship said goodnight to Desford outside his bedroom, he was in perfect charity with him, partly because he was so much relieved to know that his heir was not contemplating matrimony with the daughter of a man whom he had no hesitation in saying was the greatest rascal he had ever known, and partly because he had succeeded in winning two out of the three rubbers of picquet he had played with him.

Before he left for London on the following day Desford was able to have some private conversation with his mother, while Lord Wroxton was engaged with his bailiff. She took him to see the improvements she had made in the rose-garden, and as they strolled down the walks together he asked her, lifting a quizzical eyebrow at her, whether he had her to thank for the welcome accorded to him by his father.

“No, no, Ashley! I didn’t utter a word in your defence!” she assured him. “Indeed, I said I would never have believed it of you, and was never more shocked in my life!”

“What a very sure card you are, Mama!” he said appreciatively. “In fact, I did owe my pardon to you!”

She smiled, but shook her head. “You may always be sure of his pardon, my dear, however much you may have vexed him. But perhaps you might not have won it as quickly if I had been so gooseish as to have tried to plead your cause, for nothing, you know, makes Papa more obstinate than opposition, and he was very angry. You’ll own that he can scarcely be blamed! The intelligence that his eldest son had apparently formed a close connection with a member of a family which he holds in the greatest contempt came as a severe shock to him.”

He nodded, grimacing. “Yes, I knew he would fly up into the boughs if he heard that I was having any dealings whatsoever with a Steane, which was why I hoped he never would hear of it. Do you wonder why I took her to Hetta, instead of bringing her here? It wasn’t that I doubted your understanding of the case, I promise you! But his I did! Recollect, too, Mama, that I was already in his black books! He told me, on the occasion of my last visit, that he didn’t wish to see my face again, and, from what Simon told me, when I ran smash into him at Inglehurst on the day I took Cherry there, his temper had not improved!”

“Alas, no!” she sighed. “Poor Simon! I was so sorry for him, and he bore it all so patiently! But I was sorry for Papa too, because whenever he rakes any of you down, and says things he doesn’t in the least mean, he is always thrown into gloom afterwards, and wishes he hadn’t been so mifty. Not, of course, that he would admit it—though he did say after your last visit, dearest, that if you supposed he meant it when he told you he never wanted to see your face again you must be a bigger mutton-head than he had thought possible. He assured me that there was no occasion for me to worry about it, since he hadn’t a doubt you’d come back very shortly—not that he cared a rush how long you stayed away! So you must never think that he doesn’t hold you in affection!”

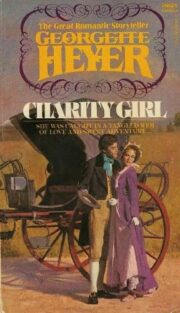

"Charity Girl" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Charity Girl". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Charity Girl" друзьям в соцсетях.