He burst out laughing. “Proof positive, Mama!”

“Well, of course it is! You know his way, Ashley! He would think it shocking weakness to betray to any of you how dearly he loves you! But I must say that nothing could have been more unfortunate than that you and Simon should have chanced to pay us visits at just that time. He was sadly out of frame, you know, not only because his gout was paining him so much, but because the new medicine which had been prescribed for him didn’t suit his constitution at all. I’m bound to say that it did do his gout good, which was why he persevered with it, but it had a very lowering effect on him, so that I was glad when our good doctor substituted for it a diet-drink of dock-roots, which suits him much better.” She smiled, and said: “But seeing you, and having made his peace with you, will have done him more good than all the medicines in the world.”

He glanced quickly down at her. “Is that a hint to me that it’s my duty to make Wolversham my headquarters, ma’am? I have a great regard for my father—indeed, I think few men have a better father!—but I couldn’t live with him!”

“Well, I don’t think he could live with you either,” she replied composedly. “You would be certain to rub against each other, for you are both so dreadfully determined! You have only to go on in just the same way, giving us a look-in every now and then, and as long as you don’t give him cause to suspect you of being on the brink of an imprudent marriage he will be very well pleased with you!”

“He need never fear, ma’am, that I could ever be so lost to all sense of what I owe not only to him, but to my name as well, as to do anything that would make him regard me as a—oh, as a broken feather in the Carrington wing!”

She smiled a little at that. “No, my dear: I am very sure he need not! And if you had wished to marry Miss Steane he would have tried to make the best of it, however disappointed he would have been, for he didn’t dislike her, and he certainly didn’t think her a designing girl. Indeed, he told me that he found it hard to believe she was Wilfred Steane’s child! And, you know, dearest, even if he had taken her in the most violent dislike, and you had married her in the teeth of his opposition, he wouldn’t have disowned you! No matter what any of you did, or how angry he was, that is something which he would never do, for it is wholly against his principles.”

“Yes, I know it is,” Desford agreed, a smile of affectionate amusement warming his eyes. “We all do—and it is what makes it quite impossible for any of us to do anything which we know would wound him to the heart! And it is also what makes him such an excellent parent! Horry nicked the nick when he told me, once, that, for his part, Papa (in one of his tantrums) was at liberty to lay anything he liked to his dish, because he could be depended on, in the last resort, to stand buff in defence of his sons!”

“Ah, you do know that, Ashley!” Lady Wroxton said, giving his arm an eloquent squeeze.

“Of course I do, Mama!” he said reassuringly. “But what a funny one he is! At one moment he can say that Wilfred Steane deserved to be disowned, and at the next give the cut direct to Nettlecombe for having done it!”

“For shame!” said Lady Wroxton, but with a quivering lip. “How dare you speak so improperly? You have quite misunderstood the matter! Naturally Papa said that, because it was perfectly true; but, in his opinion, Lord Nettlecombe behaved in a manner unworthy of a father, and that was true too! So there was nothing inconsistent in his having condemned both of them, and I will not permit you to call him a funny one!”

“Now that you have explained the matter to me, Mama, I perceive that I was quite beside the bridge to have done so,” he replied.

She was not deceived by his air of grave remorse, but said, with an involuntary chuckle: “Quite beside it, wicked, odious, impertinent boy that you are!” She paused, and removed her hand from his arm to nip off a withered rose from one of the standards. “By the by, do you remember my telling you about Mr Cary Nethercott? Old Mr Bourne’s nephew, I mean, who lately came into the property?”

“Yes. Why?”

“Oh, merely that I met him, when Papa and I drove over to Inglehurst! I never had, you know, so—”

“Met him at Inglehurst, did you? I suppose he called there to give Lady Silverdale some journal to read! Or had he another excuse?”

Startled by the sardonic note in his voice, she shot a quick glance at him, before answering with her usual calm: “My dear, how should I know? He was there when we arrived, sitting on the terrace with Hetta and Miss Steane, so what excuse he may have made for his visit I haven’t a notion—if he made any! I formed the impression that he stands on such friendly terms with the Silverdales that he is free to drop in at Inglehurst whenever he chooses.”

“Runs tame there, does he? How Hetta can tolerate such a prosy fellow I shall never know!”

“Oh, you’ve met him then?” she said.

“I should rather think I have! I trip over him every time I go to Inglehurst!”

“And you don’t like him? I thought him a pleasant, well-conducted man.”

“Well, I think him a dead bore!” said Desford.

She returned an indifferent answer, and almost immediately turned the subject, repressing, with a strong effort, a burning desire to pursue it.

The Viscount set out for London after partaking of a light luncheon, sped on his way by a recommendation from his father to post off to Bath first thing next day, and not to lie abed till all hours (“as you lazy young scamps like to do!”), because the sooner he finished with “this business” the better it would be for all concerned in it.

“For once, sir, I am in complete agreement with you!” returned the Viscount, a laugh in his eyes. “So much so that I shall sleep at Speenhamland tonight!”

“Oh, you will, will you? At the Pelican, no doubt!” said his lordship, with awful sarcasm.

“But of course, Papa! Where else should one put up on the Bath road?”

“I might have guessed you would choose the most expensive house in the country to honour with your patronage!” said the Earl. “When I was your age, Desford, I couldn’t have stood the nonsense, let me tell you! But I had no bird-witted great-aunt to leave her fortune to me! Oh, well, it’s no concern of mine how you waste the ready, but don’t come to me when you find yourself in Dun Territory!”

“No, no, you’d disown me, wouldn’t you, sir? I shouldn’t dare!” said the Viscount, audaciously quizzing him.

“Be off with you, wastrel!” commanded his austere parent.

But when the Viscount’s chaise had disappeared from sight he turned to nod at his wife, and to say: “This business has done him a deal of good, my lady! I own that I was a trifle put out when I first got wind of it, but there was never the least need for you to think he’d been caught by some designing hussy!”

“No, my dear,” meekly agreed his life’s companion.

“Of course it was no such thing! Not but what it was a lunk-headed thing to have done—However, I shall say no more on that head! The thing is that for the first time in his life he has a wolf by the ears, and he ain’t running shy! He’s ready to stand buff, and, damme, I’m proud of him! Sound as a roast, my lady! Now, if only he would settle down—form an attachment to some eligible female—I’d hand Hartleigh over to him!”

“An excellent scheme!” said Lady Wroxton. “How delightful it will be, my love, to see Ashley where you and I lived until your father deceased!”

“Ay, but when?” responded his lordship gloomily. “That is the question, Maria!”

“Not so very long, I fancy!” said Lady Wroxton, with a smothered laugh.

Chapter 12

While the Viscount was impatiently awaiting the fashioning of a tyre to fit the wheel of his chaise, his youngest brother had been half-way back to London from Newmarket, with one of his chief cronies seated beside him in his curricle. Both gentlemen were in excellent spirits, having enjoyed a most profitable sojourn at Newmarket. Mr Carrington, in fact, was appreciably plumper in the pocket than his friend, for when, having boldly wagered his all on the Viscount’s tip, and watched Mopsqueezer gallop home a length ahead of his closest rival, he had seen that a horse named Brother Benefactor was running in the last race he had instantly, ignoring the earnest pleas of his well-wishers not to be such a gudgeon, backed this animal to the tune of a hundred pounds. As it won by a head at the handsome price of ten-to-one, he left the course in high fettle, and with his pockets bulging with rolls of soft, one of which was considerably diminished at the end of the evening which he spent in entertaining several of his intimates to a sumptuous dinner at the White Hart.

Having a hard head and a resilient constitution, he arose on the following day feeling (as he himself expressed it) only a trifle off the hinges, and in unimpaired good spirits. The same could not have been said of his companion, whose appearance caused Simon to exclaim: “Lord, Philip, you look as blue as a razor!”

“I’ve got a devilish headache!” replied the sufferer, eyeing him with loathing.

“That’s all right, old fellow!” said Simon encouragingly. “You’ll be in a capital way as soon as you get out into the fresh air! Nothing like a drive on a fine, windy day to pluck a man up!”

Mr Harbledon vouchsafed no other response to this than a sound between a groan and a snarl. He climbed into the curricle, winced when it moved forward with a jerk, and for the next hour gave no other signs of life than moans when the curricle bounced over a bad stretch of ground, and one impassioned request to Simon to refrain from singing. Happily, his headache began to go off during the second hour, and by the time Simon pulled in his pair at the Green Man, in Harlow, he was so far restored as to be able to take more than an academic interest in the bill of fare, and even to discuss with the waiter the rival merits of a neck of venison and a dish of ox rumps, served with cabbage and a Spanish sauce.

Simon reached his lodging in Bury Street midway through the afternoon on the following day. Since neither he nor Mr Harbledon was pressed for time they had tacitly agreed to recruit nature by remaining in bed until an advanced hour. They had then eaten a leisurely and substantial breakfast, so that by the time they left the Green Man it was past noon. Still full of fraternal gratitude, Simon strolled round to Arlington Street, on the chance that he might find Desford at home. He was not much surprised when Aldham, who opened the door to him, said that his lordship was not in at the moment; but when he learned, in answer to a further enquiry, that his lordship had not yet returned from Harrowgate, he opened his eyes in astonishment, and ejaculated: “Harrowgate?”

“Yes, sir. So I believe,” said Aldham.

Simon was not wanting in intelligence, and it did not take him more than a very few moments to realize what must have made his brother go off on such a long and tedious journey. He uttered an involuntary choke of laughter, but after eyeing Aldham speculatively decided that it would be useless to try to coax any further information out of him. Besides, for anything he knew, Aldham might not have been taken into Desford’s confidence. So he contented himself with leaving a message for his brother, saying: “Oh, well, when he comes home tell him I shall be in London until the end of the week!”

“Certainly I will, Mr Simon!” said Aldham, much relieved to be rescued from the horns of a dilemma. He regarded Simon with indulgent fondness, having known him from the cradle, but he knew that Simon was inclined to be a rattlecap; and since he had learnt from Pedmore that one of the first duties incumbent upon a butler was to be unfailingly discreet, and never, on any account, to blab about his master’s activities, he would have been hard put to it to answer any more searching questions without either betraying the Viscount, or offending Mr Simon.

Simon was engaged to join a party of friends at Brighton, and might well have gone there in advance of the rest of the party if he had not recollected that rooms at the Ship had been booked from the Saturday of that week. Only a greenhead would suppose that there was the smallest chance of obtaining any but the shabbiest of lodgings in Brighton, at the height of the season, if he had not booked accommodation there; so he was obliged to resign himself to several days spent in kicking his heels in London, which, in July, more nearly resembled a desert, to any member of the ton, than a fashionable metropolis. Not that London had nothing to offer for the entertainment of out of season visitors: it had several things, and Simon was considering, two days after his call in Arlington Street, whether the evening would be more amusingly spent at the Surrey Theatre, or at the Cockpit Royal, when the retired gentleman’s gentleman who owned the house in Bury Street, and ministered to the three gentlemen at present lodging there, entered the room and presented him with a visiting-card, saying succinctly: “Gentleman to see you, sir.”

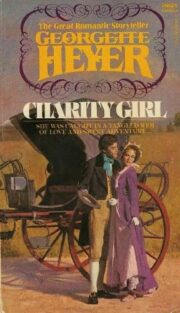

"Charity Girl" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Charity Girl". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Charity Girl" друзьям в соцсетях.