“Then why the deuce don’t you settle your debts?” asked Simon sceptically.

Shocked by this suggestion, Mr Steane exclaimed: “Waste the ready on my creditors? I am not such a spill-good as that, I hope! Nor let me tell you, as unmindful of my duty to my child! I had no other purpose in returning to the land of my birth than to succour her. Conceive what were my feelings when I arrived in Bath, yearning to clasp her in my arms, only to discover that the Creature to whom I had entrusted her had cast her off! Delivered her, in fact, into the hands of one of my bitterest enemies! And why? Because, if you please, in the midst of my struggles to bring myself about I had been obliged to defer the payment of her bills! Could she not have reposed as much confidence in my integrity as I had reposed in hers? Did she doubt that as soon as it became possible for me to do so I should have discharged my debt to her in full? Her only reply to these home-questions was a flood of tears.” He paused, directing a challenging stare at Simon; but as Desford had divulged only the bare outlines of the circumstances which had led him to befriend Cherry, Simon had no comment to offer. So Mr Steane continued his narrative. “I repaired instantly to Amelia Bugle’s country residence. It cost me a severe struggle to do so, but I mastered my repugnance: my parental feelings overcame all other considerations. And what was my reward? To be informed, Mr Carrington, that my innocent child had been ravished from the safety of her maternal relative’s home by none other than my Lord Desford!”

“If that’s what Lady Bugle told you, she was lying in her teeth!” Simon said. “He did no such thing! Lady Bugle treated Miss Steane so abominably that she ran away—meaning to seek refuge with her grandfather! All Desford did was to take her up in his curricle, when he overtook her trudging up to London!”

Mr Steane smiled pitifully at him. “Is that his story? My poor boy, it grieves me to be obliged to destroy your faith in your brother, but—”

“It needn’t, for you won’t do it!” interjected Simon, at white heat. “And I’ll thank you not to call me your boy!”

“Young man,” said Mr Steane sternly, “remember that you are speaking to one who is old enough to be your father!”

“And do you remember, sir, that you are speaking of one who is my brother!” Simon countered.

“Believe me,” said Mr Steane earnestly, “I enter most sincerely into your feelings! I was never, I regret to say, blessed with a brother for whom I cherished the smallest partiality, but I can appreciate—”

“Partiality be damned!” interrupted Simon. “Ask anyone who knows him whether Desford is the sort of loose screw to ravish a chit of a girl away from her home! You’ll get the same answer you’ve had from me!”

Mr Steane heaved another of his gusty sighs. “Alas, you force me to divulge to you, Mr Carrington, that I fear my unhappy child fell willingly into his arms! It rends me to the heart to be obliged to tell you this—and I need hardly describe to you how grievous a blow to me it was to learn that she had, in her innocence, succumbed to the lure of a libertine possessed of a handsome face, and engaging address. Not to mention the advantages of birth and fortune. I am led to believe that Lord Desford is possessed of these attributes?”

Revolted by this description of his eldest brother, Simon repudiated it, saying shortly: “No, he ain’t! He’s well-enough, I daresay—never thought about it, myself!—but as for an engaging address—! Lord, it makes him sound like a simpering, inching macaroni merchant! I’ll have you know, sir, that Desford is a gentleman! What’s more, your daughter didn’t fall into his arms, because he never held them out to her! Not that I mean to say she would have done so if be had, for I am not one to cast aspersions on another man’s close relations! And also, Mr Steane, if you weren’t old enough to be my father I’d dashed well plant you a facer for having the infernal brass to call Desford a libertine!”

Mr Steane, listening to this heated speech with unimpaired equanimity, said compassionately, at the end of it: “I perceive that he has you in a string, and deeply do I pity you! You remind me so much of what I was in my youth! Hot-headed, perhaps, but replete with generous impulses, misplaced loyalties, and a touching faith in the virtue of those whom you have been taught to revere! Sad, inexpressibly sad is it that it should have fallen to my lot to shatter that simple faith!”

“What the devil—? demanded Simon explosively. “If you think that I was taught to revere Desford—or that I do revere him!—you’re fair and far off, Mr Steane! Of course I don’t! But—but—he’s a damned good brother, and—and though I daresay he may have his faults he ain’t a rabshackle—and that you may depend on!”

“Would that I could!” said Mr Steane regretfully. “Alas that I cannot! Are you ignorant, my poor young man, of the way of life your brother has pursued since he made his come-out, and—I am compelled to say—is still pursuing?”

Simon stared at him, wrath and incredulity in his eyes. The flush that had risen to his face when he had found himself compelled to violate every canon of decent reticence by upholding Desford’s virtue darkened perceptibly. In a voice stiff with pride, he said: “My good sir, if, by those—those opprobrious words you mean to say that my brother has ever, at any time, or in any way, conducted himself in a manner unbefitting a man of honour, I take leave to tell you that you have either been grossly misinformed, or—or you are a damned liar!” He paused, his jaw dangerously out-thrust, but as Mr Steane evinced no desire to pick up the gage so belligerently flung down, but continued to sit at his ease, blandly regarding him, he said haughtily: “I collect, sir, that when you speak of my brother’s way of life, you refer to certain—certain connections he has had, from time to time, with members of the muslin company. But if you mean to tell me that you suspect him of seducing innocent females, or—or of littering the town with his butter-prints, you may spare your breath! As for the suggestion that he lured your daughter to elope with him—Good God, if it were not so damned insulting I could laugh myself into whoops at it! If he had fallen so desperately in love as to have done anything so kennel-raked, why the devil should he be doing his utmost to give her into her grandfather’s keeping? Answer me that, if you can!”

Mr Steane shuddered eloquently, and replied in a manner worthy of a Kemble or a Kean: “If he has indeed done so, my dread is that he has wearied of her, and is seeking to fob her off!”

“What, in less than two days?” said Simon jeeringly. “A likely story!”

“My dear young greenhead,” said Mr Steane, with a touch of asperity, “one can discover that a female is a dead bore in less than two hours! Not that I believe this Banbury story of his having gone off to Harrowgate in search of my father! It’s a bag of moonshine! The more I think about it the greater becomes my conviction that he has abducted my innocent child, and bamboozled everyone into believing that he only did so because he thought she would be happier with her grandfather than with her aunt. Now, I don’t doubt she may have been unhappy in that archwife’s house, but if your precious brother thought she would be happier in my father’s house he might be no better than a blubber-head, which I know very well he isn’t! No, no, my boy! You may swallow that Canterbury tale, but don’t expect me to! The plain truth is that he’s bent, on ruining my poor little Cherry, thinking that she has no one to protect her. He will discover his mistake! Her father will see her righted! Ay! even if he—her father, I mean, or, in a word, myself!—has to publish the story of his infamy to the world! If he has the smallest claim to be a man of honour he can do no less than marry her!”

“You’ve taken the wrong sow by the ear, sir!” said Simon, looking at him from between suddenly narrowed eyelids. “I’m happy to be able to inform you that your daughter’s reputation is unblemished! So far from being bent on ruining her, my brother was bent on ensuring that no scandal should attach to her name! And I am even happier to inform you that she is residing, thanks to Desford’s forethought, in an extremely respectable household!”

It would have been too much to have said that Mr Steane’s countenance betrayed chagrin, but the bland smile certainly faded from his lips, and although his voice retained its smoothness its tone was somewhat flattened when he replied to what Simon, who had formed a pretty accurate idea of his character, believed to be an unwelcome piece of information. Simon began to feel a little uneasy, and to wish that he knew where Desford was to be found. Dash it all, it was Desford’s business to deal with Mr Steane, not his! Desford would be well-served if he disclosed Cherry’s exact whereabouts to this old countercoxcomb, and washed his hands of the whole affair.

“And where,” enquired Mr Steane, “is this respectable household situated?”

“Oh, in Hertfordshire!” said Simon carelessly.

“In Hertfordshire!” said Mr Steane, sitting up with a jerk. “Can it be that I have wronged Lord Desford? Has he made her an offer? Do not be afraid to confide in me! To be sure, he should have obtained my permission to address himself to Cherry, but I am prepared to pardon that irregularity. Indeed, if he supposed me to be dead his informality must be thought excusable.” He wagged a finger at Simon, and said archly: “No need to be discreet with me, my boy! I assure you I shall raise no objection to the match—provided, of course, that Lord Desford and I reach agreement over the Settlement, which I have no doubt we shall do. Ah, you are wondering how I have guessed that the respectable household to which you referred can be none other than Wolversham! I have never had the pleasure of visiting the house, but I have an excellent memory, and as soon as you spoke of Hertfordshire I recalled, in a flash, that Wolversham is in Hertfordshire. A fine old place, I believe: I shall look forward to seeing it.”

Momentarily stunned, Simon pulled himself together, and lost no time in dispelling the illusion which was obviously working powerfully on Mr Steane’s mind. “Good God, no!” he said. “Of course he hasn’t taken her to Wolversham! He wouldn’t dare! You must know as well as I do, sir, how my father regards you—well, you’ve told me yourself that he gave you the cut direct, so I needn’t scruple to say that nothing would ever prevail upon him to give his consent to Desford’s marriage to Miss Steane! Not that there’s the least likelihood of his being asked to do so, because there ain’t! Desford has not made an offer, because, for one thing, he ain’t in love with her; for another, there’s no reason why he should; and for a third—well, never mind that!”

He had the satisfaction of seeing Mr Steane’s radiant smile fade from his face, but it was short lived. A calculating look came into that gentleman’s eyes, and his next words almost made the hair rise on Simon’s scalp. “I fancy, young man,” said Mr Steane, “that you will find you are mistaken. Yes. Very much mistaken! I can well believe that your honoured parent will not favour the match, but I venture to say that I believe he would favour still less an action of breach of promise brought against his heir.”

“Breach of promise?” ejaculated Simon. “You’d catch cold at that, Mr Steane! Desford never made your daughter an offer of marriage!”

“How do you know that?” asked Mr Steane. “Were you present when he stole her out of her aunt’s house?”

“No, I was not! But he told me how it came about that he was befriending Miss Steane—”

He stopped, for a slow smile had crept over Mr Steane’s face, and he was shaking his head. “It is easy to see that you can have little knowledge of the law, young man. What your brother may have told you is not evidence. If it were admitted—which I can assure you it wouldn’t be!—it could scarcely outweigh my unfortunate child’s evidence!”

“Do you mean to say,” gasped Simon, “that you think your daughter is the kind of girl who would stand up in a court of law, and commit perjury? Your memory isn’t as good as you suppose, if that’s what you think! Why, she’s no more than a chit of a schoolgirl that hasn’t cut her eye-teeth!”

“Ah!” said Mr Steane, putting Simon forcibly in mind of a cat confronted with a saucer of cream. “I collect, Mr Carrington, that you have met my little Cherry?”

“Yes, I’ve met her! And if she had accepted an offer from Desford, why, pray, didn’t she tell me so?”

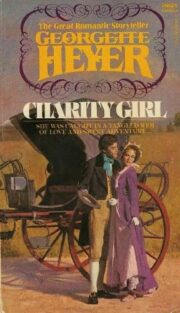

"Charity Girl" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Charity Girl". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Charity Girl" друзьям в соцсетях.