“No, indeed! And what was her papa’s reply to this very just rebuke?” he enquired, much entertained by this artless recital.

“Oh, he merely said that she might think herself fortunate that she hadn’t been christened Sappho, and that if it hadn’t been for him she would have been. It doesn’t sound to me any worse than Corinna, but I believe there was a Greek person of that name who wasn’t at all the thing. Oh, pray don’t laugh so loud, sir!”

He had uttered an involuntary crack of laughter, but he checked it, and begged pardon. He had by this time had time to assimilate the details of her dress and person, and had realized that her figure was elegant, and that her dress had been adapted rather unskilfully from one originally made for a much bigger girl. He also realized, being pretty well experienced in such matters, that it was a trifle dowdy, and that her soft brown ringlets had not enjoyed the ministrations of a hairdresser. It was the fashion for ladies to have their locks cropped and curled, or twisted into high Grecian knots from which carefully brushed and pomaded clusters of curls fell over their ears; but this child’s hair fell loosely from a ribbon tied round her head, several strands escaping from it, which gave her a somewhat dishevelled appearance.

Desford said abruptly: “How old are you, my child? Sixteen? Seventeen?”

“Oh, no, I am much older than that!” she replied. “I’m as old as Lucasta—all but a few weeks!”

“Then why are you not downstairs, dancing with the rest of them?” he demanded. “You must surely be out!”

“No, I’m not,” she said. “I don’t suppose I ever shall be, either. Unless my papa turns out not to be dead, and comes home to take care of me himself. But I don’t think that at all likely, and even if he did come home it wouldn’t be of the least use, because he seems never to have sixpence to scratch with. I am afraid he is not a very respectable person. My aunt says he was obliged to go abroad on account of being monstrously in debt.” She sighed, and said wistfully: “I know that one ought not criticize one’s father, but I can’t help feeling that it was just a little thoughtless of him to abandon me.”

“Do you mean that he left you in your aunt’s charge?” he asked, his brows drawing together. “He can’t have abandoned you!”

“Well, he did,” she said. “And it was horridly uncomfortable, I can tell you, sir! I was still at school, in Bath, you see—and I must own that Papa did pay the bills, when he was in funds, and Miss Fletching was very kind, and she never told me that he had stopped doing so until she was obliged to realize that he wasn’t going to remember that he owed her for a whole year. She disclosed to me afterwards that for a long time she expected to get a letter from him, or even a visit, for he did sometimes come down to see me. And it seems he had never been very punctual in paying Miss Fletching, so that she was quite in the habit of waiting. And I fancy she had a tendre for him, because she was for ever saying what a handsome man he was, and how particularly affable, and what distinguished manners he had. She was fond of me, too: she said it was because I had lived with her for such a long time, which I had, for Papa placed me in the school when my mama died, and I was only eight years old then, and lived at school all the year round.”

“You poor child!” he exclaimed.

“Oh, no!” she assured him. “In the holidays my friends amongst the day-boarders often invited me to their parties, or took me with them on expeditions, and Miss Fletching several times took me to the theatre. I was perfectly happy—indeed, I don’t suppose I shall ever be so happy again. But naturally I couldn’t remain there for ever, so Miss Fletching was obliged to write to my grandfather. But it so happens that he had disowned Papa years and years before, and he wrote very uncivilly to Miss Fletching, saying that he wanted to know nothing about his ramshackle son’s brats, and recommending her to apply to my mama’s relations. Which—is how I come to be here.”

She ended on a forlorn note, which made Desford say gently: “But you’re not happy here, are you?”

She shook her head, but said, with a valiant attempt to smile: “Not very happy, sir. But I do try to be, because I know I am very much obliged to Aunt Bugle for—for giving me a home, when she held Papa in the utmost aversion, and had had a terrible quarrel with my mama when Mama eloped with him, and never forgave her. Which makes it my duty to be grateful to her, don’t you think?”

“Who is your father?” he demanded, not answering this question. “What is his name? And what is your name?”

“Steane,” she replied. “Papa is Wilfred Steane, and I am Cherry Steane.”

“Well, you have a very pretty name, Miss Steane!” he said, smiling down at her. “But—Steane? Are you related to old—to Lord Nettlecombe?”

“Yes, he’s my grandfather,” she said. “Are you acquainted with him, sir?”

“No, I haven’t that honour,” he replied rather dryly. “I have, however, met your Uncle Jonas, and as I’ve been credibly informed that he closely resembles his father I am strongly of the opinion, my child, that you are better off with your aunt than you would be with your grandfather! But why should we waste our time talking about either of them? You have told me your name, but it occurs to me that you don’t know mine! It is—”

“Oh, I know who you are!” she said. “You are Lord Desford! I knew that when I saw you waltzing with Lucasta. That’s why I was looking through the bannisters: you can see this end of the drawing-room from here, you know. I saw you first when you came down the country dance, but I couldn’t be positive it was you until I caught a glimpse of you waltzing with Lucasta.”

“And then you were positive?” he said, in some amusement. “Why?”

“Oh, because I heard Aunt Bugle tell Lucasta she might waltz if you invited her to!” she replied blithely. Then her expression changed swiftly, as some faint sound in the shadows behind her came to her ears, and the wary, frightened look returned to her face. She whispered: “I mustn’t stay! That was a board creaking! Please, oh, please go away, and pray take care no one sees you going down the stairs!”

She was gone on the words, as noiseless as a ghost; and the Viscount, having assured himself that the coast was clear, walked calmly down the stairs, and went back into the ballroom.

Chapter 4

Seizing on the excuse offered by her daughter’s fear of being driven back to Hazelfield through a thunderstorm, Lady Emborough carried her party off immediately after supper. Lady Bugle was regretful, but since she was even more frightened of lightning than was Emma she fully sympathized with her alarms, and made no effort to delay the departure, prophesying, when she heard that a storm was brewing, that a great many others would also leave early: certainly all those faced with a drive of more than half-an-hour.

The Redgraves took up Edward and Gilbert in their carriage, and Desford occupied the fourth seat in the Emborough landaulet, sitting beside his uncle, and confronting Lady Emborough and Miss Montsale. For the first few minutes the ladies discussed the ball, but presently Miss Montsale said that although she had been prepared to find that Miss Bugle fell short of the enthusiastic descriptions furnished by Ned and Gil she had no sooner set eyes on her than she felt that they had underrated her beauty rather than exaggerated it. “Such great, sparkling eyes!” she said. “Such a lovely complexion, and such glorious hair! Oh, I thought she was one of the most beautiful creatures I’ve ever seen! Did not you, Lord Desford?”

He was not, like his uncle, drowsing, but he was obviously abstracted, and she had to repeat her question to recall him from whatever thoughts were occupying his mind. He said: “I beg pardon! I wasn’t attending! Miss Bugle? Oh, yes, undoubtedly! A dazzling piece of nature!”

“And not just in the common style!”

“By no means!”

“What do you think, Desford? Will she take?” asked Lady Emborough.

“Lord, yes!”

“Well, I hope she will. I don’t like her mother above half, but I do sincerely pity her, for it’s no laughing matter to have five daughters to establish creditably when one hasn’t a large enough fortune to grease the wheels,” she said bluntly. “There’s one that ought to be brought out next Season, and so she would be if old Lady Bugle hadn’t chosen to die at the most inconvenient time she could! Lucasta might have been engaged by now, which would have made it possible for the next one—I can’t remember her name! they all have the most outlandish names!—to have been allowed to try her wings at that little affair tonight, and to have been brought out during the Little Season, this autumn. Not what one would choose, of course, but what’s to be done, when the girl is turned seventeen already, and her elder sister has scarcely been seen yet, much less turned-off? And before that unfortunate woman has time to make a recover she’ll have the third girl ready for her come-out!”

“Tell me, ma’am!” interposed Desford. “What do you know about Lady Bugle’s niece? Have you met her?”

“Why, have you met her?” she asked, considerably surprised.

“Yes, I met her tonight,” he answered. “But pray don’t divulge that to her aunt! She was peeping through the bannisters to watch as much as she could see of the dancing, and I happened to catch sight of her. I thought her one of the children at first, but discovered that she is—all but a few weeks!—as old as her cousin Lucasta. A pretty child, with big, scared eyes, a tangle of brown hair, and a deplorably outmoded and ill-fitting gown.”

Lady Emborough tried hard to see his face, but it was too dark inside the carriage for her to distinguish more than its outlines. She said: “Yes, I think I have seen her once. I must own, it astonishes me to learn that she is as old as Lucasta, for—like you!—I thought her a schoolroom miss! A poor little dab of a girl, isn’t she? Well, she’s the daughter of Lady Bugle’s only sister, who ran off with that ne’er-do-well son of old Nettlecombe’s. Before your time, but I remember what a scandal it was! Lady Bugle was obliged to take this girl under her roof—oh, a little over a year ago! I forget the rights of it, but I know that I thought it very charitable of her to have done so, when she told me about it.”

“Oh, was that how it was?” he said, in an indifferent tone.

“Charitable?” said Miss Montsale. “Why, yes—if the charity was not used as a cloak to cover more mercenary aims!”

“Good God, Mary, what in the world do you mean?” demanded Lady Emborough.

“Oh, nothing, dear ma’am, against Lady Bugle! How could I, when I never met her before tonight? But I have so often seen—as I am persuaded you too must have seen!—the—the indigent female who has been received into the household of one of her more affluent relations, as an act of charity, and has been turned into a drudge!”

“And has been expected to be grateful for it!” struck in the Viscount.

“If,” said Lady Emborough awfully, “these remarks refer to my cousin Cordelia’s position at Hazelfield—”

“Oh, no, no, no!” Miss Montsale assured her laughingly. “Of course they don’t! Lord Desford, could anyone suppose Miss Pembury to be a downtrodden drudge?”

“Certainly not!” he responded promptly. “No one, that is to say, who had been privileged to hear her giving handsome setdowns to my aunt! But you are very right, Miss Montsale: I too have seen just what you have described, and I suspect that the child I met tonight may be an example of that sort of charity.”

No more was said, for by this time the carriage had drawn up before the imposing portals of Hazelfield House. The ladies were handed down from it; Lord Emborough was roused by his nephew from his gentle slumber; and his sons, springing down from the Redgrave carriage, which drew up a minute later, were indignantly calling upon their pusillanimous sister to own that the storm was still miles distant, and that it had been a great shame to have dragged them away from the ball when (according to them) it had scarcely begun.

Lord Emborough, on entering his house, presented all the appearance of a gentleman no more than half awake, but when he walked into my lady’s bedchamber, an hour later, he had emerged from his drowsy mists, and so obviously wished to engage her in private conversation that she dismissed her abigail, who was in the act of fitting a nightcap over her iron-grey locks, and said, as this excellent female curtsied herself out of the room: “Now we can be comfortable, and talk about the party—which I have for long thought to be the best thing about parties, even the finest of ‘em! Which the lord knows this wasn’t! An insipid evening, wasn’t it?”

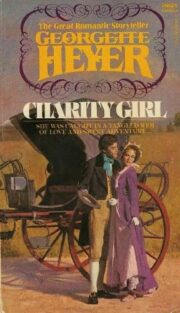

"Charity Girl" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Charity Girl". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Charity Girl" друзьям в соцсетях.