"What about your dad?" I asked her. "Could your dad buy you some more Barbie clothes?"

Keely said, lifting Barbie from the sand and then smoothing her hair back, "My daddy's in heaven."

Well. That settled that, didn't it?

"Who told you that your daddy is in heaven, Keely?" I asked her.

Keely shrugged, her gaze riveted to the plastic doll in her hands. "My mommy," she said. Then she added, "I have a new daddy now." She wrenched her gaze from the Barbie and looked up at me, her dark eyes huge. "But I don't like him as much as my old daddy."

My mouth had gone dry … as dry as the sand beneath our feet. Somehow I managed to croak, "Really? Why not?"

Keely shrugged and looked away from me again. "He throws things," she said. "He threw a bottle, and it hit my mommy in the head, and blood came out, and she started crying."

I thought about the crescent-shaped scab on Mrs. Herzberg's forehead. It was exactly the size and shape a bottle, flying at a high velocity, would make.

And that, I knew, was that.

I guess I could have gotten out of there, called the cops, and let them handle it. But did I really want to put the poor kid through all that? Armed men knocking her mother's door down, guns drawn, and all of that? Who knew what the mother's bottle-throwing boyfriend was like? Maybe he'd try to shoot it out with the cops. Innocent people might get hurt. You don't know. You can't predict these things. I know I can't, and I'm the one with the psychic powers.

And yeah, Keely's mother seemed like kind of a freak, protesting that her kid only watches public television while standing there filling that same kid's lungs with carcinogens. But hey, there are worse things a parent could do. That didn't make her an unfit mother. I mean, it wasn't like she was taking that cigarette and putting it out on Keely's arm, like some parents I've seen on the news.

But telling the kid her father was dead? And shacking up with a guy who throws bottles?

Not so nice.

So even though I felt like a complete jerk about it, I knew what I had to do.

I think you'd have done the same thing, too, in my place. I mean, really, what else could anybody have done?

I stood up and said, "Keely, your dad's not in heaven. If you come with me right now, I'll take you to him."

Keely had to crane her neck to look up at me. The sun was so bright, she had to do some pretty serious squinting, too.

"My daddy's not in heaven?" she asked. "Where is he, then?"

That was when I heard it: the sound of Rob's motorcycle engine. I could tell the sound of that bike's engine from every single other motorcycle in my entire town.

I know it's stupid. It's more than stupid. It's pathetic, is what it is. But can you really blame me? I mean, I really did harbor this hope that Rob was pining for me, and satisfied his carnal longing for me by riding by my house late at night.

He never actually did this, but my ears had become so accustomed to straining for the sound of his bike's engine, I could have picked it out in a traffic jam.

The real question, of course, was why Rob had left Mrs. Herzberg's front porch when he had to know I wasn't finished with my business in her backyard.

Something was wrong. Something was very wrong.

Which was why I didn't suffer too much twinging of my conscience when I looked down at Keely and said, "Your daddy's at McDonald's. If we hurry, we can catch him there, and he'll buy you a Happy Meal."

Did I feel bad, invoking the M word in order to lure a kid out of her own backyard? Sure. I felt like a worm. Worse than a worm. I felt like I was Karen Sue Hanky, or someone equally as creepy.

But I also felt like I had no other choice. Rob's bike roaring to life just then meant one thing, and one thing only:

We had to get going. And now.

It worked. Thank God, it worked. Because Keely Herzberg, bless her five-year-old heart, stood up and, looking up into my face, shrugged and said, "Okay."

It was at that moment I realized why Rob had taken off. The screen door that led to the backyard burst open, and a man in a pair of fairly tight-fitting jeans and some heavy-looking work boots—and who was clutching a beer bottle—came out onto the back porch and roared, "Who the hell are you?"

I grabbed Keely by the hand. I knew, of course, who this was. And I could only pray that his aim, when it came to moving targets, left something to be desired.

The sound of Rob's motorcycle engine had been getting closer. I knew now what he was doing.

"Come on," I said to Keely.

And then we were running.

I didn't really think about what I was doing. If I had stopped and thought about it, of course, I would have been able to see that there was no way that we could run faster than Mrs. Herzberg's boyfriend. All he had to do was leap down from the back porch and he'd be on us.

Fortunately, I was too scared of getting whacked with a beer bottle to do much thinking.

Instead, what I did was, while we ran, I shifted my grip on Keely from her hand to her arm, until I had scooped her up in both hands and she was being swept through the air. And when we reached the part of the fence I'd jumped down from, I swung her, with all my strength, toward the top of the fence. . . .

And she went sailing over it, just like those sacks of produce Professor Le Blanc had predicted I was going to be spending the rest of my life bagging.

Professor Le Blanc was right. I was a bag girl, in a way. Only what I bagged wasn't groceries, but other people's mistreated kids.

I heard Keely land with a scrape of plastic sandals on metal. She had made it onto the lid of the Dumpster, where, I could only hope, Rob would grab her. Now it was my turn.

Only Keely's new bottle-throwing dad was right behind me. He had let out a shocked, "Hey!" when I'd thrown Keely over the fence. The next thing I knew, the ground was shaking—I swear I felt it shudder beneath my feet—as he leaped from the porch and thundered toward me. Behind us a screen door banged open, and I heard Mrs. Herzberg yell, "Clay! Where's Keely, Clay?"

"Not me," I heard Clay grunt. "Her!"

That was it. I was dead.

But I wasn't giving up. Not until that bottle was beating my skull into pulp. Instead, I jumped, grabbing for the top of the fence.

I got it, but not without incurring some splinters. I didn't care about my hands, though. I was halfway there. All I had to do was swing my leg over, and—

He had hold of my foot. My left foot. He had grabbed it, and was trying to drag me down.

"Oh, no, you don't, girlie," Clay growled at me. With his other hand, he grabbed the back of my jeans. He had apparently dropped the beer bottle, with was something of a relief.

Except that in a second, he was going to lift me off that fence, throw me to the ground, and step on me with one of those giant, work-booted feet.

"Jess!" I heard Rob calling to me. "Jess, come on!"

Oh, okay. I'll just hurry up now. Sorry about the delay, I'm just putting on a little lipstick—

"You," Clay said, as he tugged on me, "are in big trouble, girlie—"

Which was when I launched my free foot in the direction of his face. It connected solidly with the bridge of his nose, making a crunching sound that was quite satisfying, to my ears.

Well, I've never liked being called girlie.

Clay let go of both my foot and my waistband with an outraged cry of pain. And the second I was free, I swung myself over that fence, landed with a thump on the roof of the Dumpster, then jumped straight from the Dumpster onto the back of Rob's bike, which was waiting beneath it.

"Go!" I shrieked, throwing my arms around him and Keely, who was huddled, wide-eyed, on the seat in front of him.

Rob didn't waste another second. He didn't sit around and argue about how neither Keely nor I were wearing helmets, or how I'd probably ruined his shocks, jumping from the Dumpster onto his bike, like a cowboy onto the back of a horse.

Instead, he lifted up his foot and we were off, tearing down that alley like something NASA had launched.

Even with the noise of Rob's engine, I could still hear the anguished shriek behind us.

"Keely!"

It was Mrs. Herzberg. She didn't know it, of course, but I wasn't stealing her daughter. I was saving her.

But as for Keely's mother …

Well, she was a grown-up. She was just going to have to save herself.

C H A P T E R

11

I don't know what your feelings on McDonald's are. I mean, I know McDonald's is at least partly responsible for the destruction of the South American rain forest, which they have apparently razed large sections of in order to make grazing pastures for all the cattle they need to slaughter each year in order to make enough Big Macs to satisfy the demand, and all.

And I know that there's been some criticism over the fact that every seven miles, in America, there is at least one McDonald's. Not a hospital, mind you, or a police station, but a McDonald's, every seven miles.

I mean, that's sort of scary, if you think about it.

On the other hand, if you've been going to McDonald's since you were a little kid, like most of us have, it's sort of comforting to see those golden arches. I mean, they represent something more than just high-fat, high-cholesterol fast food. They mean that wherever you are, well, you're actually not that far from home.

And those fries are killer.

Fortunately, there was a Mickey D's just a few blocks away from Keely's house. Thank God, or I think Rob would have had an embolism. I could tell Rob was pretty unhappy about having to transport Keely and me, both helmetless, on the back of his Indian … even though it was completely safe, with me holding onto her and all. And it wasn't like he ever went more than fifteen miles per hour the whole time.

Well, except when we'd been racing down that alley to get away from Clay.

But let me tell you, when we pulled into the parking lot of that McDonald's, I could tell Rob was plenty relieved.

And when we stepped into the icy air-conditioning, I was relieved. I was sweating like a pig. I don't mind the crime-fighting stuff so much. It's the humidity that bugs me.

Anyway, once we were inside, and Keely was enjoying her Happy Meal while I thirstily sucked down a Coke, Rob explained how he'd been listening attentively to Mrs. Herzberg's description of her television-viewing habits, when her boyfriend appeared as if from nowhere, preemptively ending their little interview with a fist against the door frame. Sensing trouble, Rob hastily excused himself—though he did fork over the promised ten-dollar bill—and came looking for me.

Thank God he had, too, or I'd be the one with a footprint across my face, as opposed to Clay.

I tried to pay him back the ten he'd given to Mrs. Herzberg. He wouldn't take my money though. Also, he insisted on paying for Keely's Happy Meal and my giant Coke. I let him, thinking if I were lucky, he might expect me to put out for it.

Ha. I wish.

Then, once we'd compared notes on our adventures with Clay, I left Rob sitting with Keely while I got on the pay phone and dialed Jonathan Herzberg's office.

A woman answered. She said Mr. Herzberg couldn't come to the phone right now, on account of being in a meeting.

I said, "Well, tell him to get out of it. I have his kid here, and I don't know what I'm supposed to do with her."

I didn't realize until after the woman had put me on hold that I'd probably sounded like a kidnapper, or something. I wondered if she was running around the office, telling the other secretaries to call the police and have the call traced or something.

But I doubt she had time. Mr. Herzberg picked up again almost right away.

"Hey," I said. "It's me, Jess. I'm at a McDonald's—" I gave him the address. "I have Keely here. Can you come pick her up? I'd bring her to you, but we're on a motorcycle."

"Fifteen m-minutes." Mr. Herzberg was stammering with excitement.

"Good." I started to hang up, but I heard him say something else. I brought the phone back to my ear. "What was that?"

"God bless you," Mr. Herzberg said. He sounded kind of choked up.

"Uh," I said. "Yeah. Okay. Just hurry."

I hung up. I guess that's the only good part about this whole thing. You know, that sometimes, I can reunite kids with the parents who love them.

Still, I wish they didn't have to get so mushy about it.

It was after I'd hung up and felt around in the change dispenser to see if anybody had left anything behind—hey, you never know—that I noticed the van.

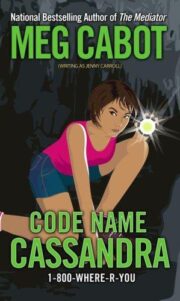

"Code Name Cassandra" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Code Name Cassandra". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Code Name Cassandra" друзьям в соцсетях.