‘I have no idea. A foreigner, I think. A Frenchman. You know what Frenchmen are like. They have a way with women. He set out to win her, and as far as I know, he succeeded.’

‘But you do not know his name?’

He thought, but then shook his head again.

‘No, I cannot recall.’ He looked at me speculatively and said, ‘What business is it of yours, if you do not object to my asking?’

‘I am ... a family friend,’ I said. ‘I am concerned about her. I want to make sure that she is well, and to assist her if she stands in need of it.’

He looked at me thoughtfully for some minutes and then said, ‘I think his name was Claude, Claude Rotterdam or some such thing. Not Rotterdam, but something like it. He used to live in Berkeley Square, in a rented house, I believe.’

I thanked him for the information and made enquiries at every house in Berkeley Square, but only one was for hire, and that had had an English tenant for over a year. I asked after the Frenchman in a number of clubs but I could find no one who could give me any information about such a man and I returned to my club in low spirits.

Saturday 21 December

It was a relief to dine with Leyton tonight and forget my troubles for a while. He had assembled a small party, but they were all interesting people: Mr and Mrs Carlton, an entertaining couple who were known to Leyton through his business; Sir John Middleton, who had just come into property in Devonshire, a few miles north of Exeter; the Doncasters, who were cousins of Leyton, with their two daughters; and the Prossers, with their daughters.

Leyton’s wife was a pretty, lively woman, and the two of them seemed very happy together. The mood was cheerful and the conversation good-natured, ranging from family affairs — Sir John’s cousin had married a widower and had had two daughters; the Prossers’ oldest son had just had his first child and Mrs Carlton’s sister was engaged — to the state of the East India Company.

After dinner, Miss Doncaster played the harp and her sister sang. It was a convivial evening.

At the end of it, Leyton’s wife gave me several hints as to the desirability of the Misses Prosser, but Leyton turned the conversation aside, for he knows I can think of no one but Eliza.

1783

Wednesday 8 January

After several promising leads, my enquiries have led nowhere, and I am still no closer to finding Eliza. I thought that when I found the new owner of her allowance, I would find some useful information, but the allowance had already changed hands several times since she parted with it, and he had no knowledge of her.

I decided, this morning, to call upon Sanders, the man Leyton recommended to me, as I could not think of anything else to do. He seemed a reliable man with a good deal of experience in finding people, and we agreed on a fee. Now it remains to be seen if he earns it.

Friday 14 February

Alas, there has been no progress. Sanders has done all he can, and so we have parted by mutual consent.

Thursday 20 February

I dined with Leyton again this evening. He, Sir John Middleton and I are becoming fast friends. It is a relief for me to have some cheerful company, for without it I would be sunk in a continual gloom. I have resisted Sir John’s good-natured efforts to find me a wife, and this evening I felt I owed him some explanation for my reluctance to marry. I hinted at an unhappy love affair and he, good fellow that he was, promised me that he would not tease me about any more young ladies.

Thursday 26 June

I ran across Parker at my club today, and we took great pleasure in discussing our lives, for we had not seen each other for years.

‘I saw one of your old servants the other day,’ he said. ‘Dawkins. A handsome fellow, and what a size! I was always in awe of him.’

He pursed his lips and shook his head.

‘He is not ill? ’ I asked.

‘No, not that. The fact of the matter is, Brandon, he has fallen on hard times. He left your father’s employ soon after you left and secured the position of butler to the Yarboroughs. He married a respectable woman who was the Yarboroughs’ housekeeper, but she became ill and he gave up his position to look after her. His savings dwindled, and after her death, he was left with large debts. I am afraid to say I came across him in a sponging-house.’

I was horrified.

‘Which one?’ I asked.

He told me, and I resolved to go and see him as soon as I could and assist him if possible.

Friday 27 June

I went to visit Dawkins this morning. The sponging-house was a run-down building in a poor part of town, and walking through the other inmates as I searched for him was something of an ordeal. Although some were well-dressed and waiting only for friends and relatives to bring them the necessary funds to release them, others were hopeless.

I saw Dawkins at last and told him how sorry I was to find him in such circumstances. After some natural shame in being found in such a position, he was pleased to see me, and he was glad that I remembered him. I offered to pay his debts, but he was too proud to let me do so. I promised him I would try to find him a position, and I left him much happier than I had found him.

I walked back through the sponging-house, trying not to look at the wretched women and children who had been detained there, but I stumbled over the uneven floor, and as I righted myself, I caught a glimpse of the bluest eyes I had ever seen. I started, and my heart began to hammer in my chest, for I thought they were Eliza’s eyes. But then I took in the woman’s wasted face and bloodless lips, her emaciated frame and her scanty hair, so different from Eliza’s thick tresses, and I knew that I was mistaken.

And yet her eyes, her eyes ...

And then they turned towards me and they locked on to my own and they looked into my soul and I let out a cry, for it was Eliza, my Eliza. But in what a place! And in what a state!

And then she was in my arms and I was cradling her against my chest and she was smiling up at me and we were lost to all else, for she was my Eliza and we were together again.

‘It is a dream,’ she said, her eyes never leaving mine as she clutched at me with weak hands. ‘But oh! What a pleasant dream.’

‘No dream,’ I said, rocking her in my arms as I tried not to weep. ‘It is real. I am here, Eliza. At long last I have found you.’

‘You came for me. I knew you would,’ she said with a sigh, leaning her weight against me.

She was so fragile that I scarcely dared embrace her and I gentled my touch. Her wasted body told me what was wrong with her even before she coughed, holding her handkerchief to her mouth and taking it away covered in blood.

‘You see I have consumption,’ she said. ‘I will not live long. But I am glad I saw you again before I died.’

‘Eliza! Oh, Eliza!’ I cried, burying my face in her hair. ‘But I must get you out of here,’ I said, recalled to the present, and the noisome place in which I had found her. Lifting her into my arms I stood up, preparing to carry her out, when she spoke.

‘My debts — ’

‘I will pay them. I will get the money somehow, no matter how heavy they are.’

‘No, James, it is no good,’ she said gently. ‘You must put me down. I cannot go with you, even if you pay my debts. I am not on my own. I have a daughter.’

A daughter. The words stopped me at once. A daughter. A child who should have been mine.

She turned her head and I followed the direction of her gaze, seeing a small child sleeping on a dirty pallet. She was about three years old, with Eliza’s features and fair hair.

‘Take care of her for me when I am gone,’ she said.

‘I will take care of both of you,’ I promised her. I put her down nevertheless. ‘Wait here a moment, there is someone I want to fetch. Dawkins, do you remember him?’

She smiled as she recalled the past.

‘Yes.’

‘He has fallen on hard times. I promised him I would try and find him a position, and it seems that I have just found him one. I will hire him to be your manservant. I will fetch him at once and he can help me take you to my lodgings, you and your daughter both. You will be safe there until I can secure something better for you.’

‘You are very good to me,’ she said.

‘I love you, Eliza,’ I said.

‘Still?’ she asked, searching my eyes.

‘Yes, still.’

She gave a sigh of contentment.

‘I should have been stronger,’ she said. ‘I should have held out against them, for I have loved only you.’

I set her down gently and went to fetch Dawkins. He was astonished when I told him that he had been in the same sponging-house as Eliza, for he thought he should have recognized her, but when he saw her so changed, he understood. I took Eliza in my arms and Dawkins carried the little girl, together with Eliza’s few belongings, and having paid her debts, I hired a hackney cab and took her back to my rooms.

She was exhausted by the time we arrived, and I left her sleeping. Dawkins stayed with her whilst I engaged a nurse to take care of her as well as a maid to look after her. Then I returned to my rooms.

She was still sleeping. I sat and watched her, tracing in the lines of her ravaged face the lines of the Eliza I had known. They were one and the same, and having reconciled the past with the present, I took her hand and held it as she slept.

Monday 30 June

I have decided to let Eliza stay in my rooms as she is too ill to be moved, and I have rented a fresh set of rooms for myself. I sat beside her all day and all night, and her suffering cut me to the heart. But for her sake I did not show it. I let her talk, pouring out all her griefs: her cruel treatment at my brother’s hands as he exposed her time after time to humiliating meetings with his mistresses; her feelings of hopelessness; her gratitude to her first seducer for a kind word; her flight from my brother’s house; her despair when her seducer left her because she had a child; her gratitude, again, for a kind word from another man, and her life with him; her destitution when again she was abandoned; her desperation; her selling of her jewellery, then her fine clothing, then last of all her allowance; and her descent still further when she had nothing left to sell.

‘And then you found me,’ she said.

‘I should never have gone away,’ I said, my heart wrung as I looked at her. ‘I thought it would make it easier for you, for both of us, but my absence left you friendless. Had I been in England, this could never have happened.’

‘Let us not dwell on the past, unless it be happy, and much of it was. All of it was, until we were separated. Do you remember the morning on the lake?’

‘How could I forget?’

‘I think of it often. I always have. Whenever life was too painful to bear I would go there in my dreams, and be with you again. You recited poetry,’ she said, smiling. ‘I liked to remember it, when I was cringing from the curses of other men. It warmed me to remember that once I had been loved, and loved by such a man as you.’

‘You are loved still, Eliza,’ I said, my voice breaking.

‘I know.’

She lifted her hand to my face, but before she could touch me, she was seized with a violent fit of coughing. I held her until it passed and she lay back, exhausted.

‘I think I will sleep now,’ she said.

She passed into slumber, and I was grateful for it. She was beyond pain in sleep, and a smile touched her lips, showing me her dreams were happy.

Wednesday 23 July

Eliza’s daughter and I are coming to know each other. The little girl, named Eliza after her mama, is intelligent and, now that she is clean, very pretty. She loves her mama, and it brings me great joy to see them together. Eliza is never happier than when her daughter is beside her, unless it is when I recite poetry to her, for we are both transported back to a sunlit world where sorrow never entered, and where we thought we would live for ever.

Thursday 14 August

Eliza was very weak today. I took her hand as she lay in bed and said:

‘If I could write the beauty of your eyes,

And in fresh numbers number all your graces,

The age to come would say, “This poet lies;

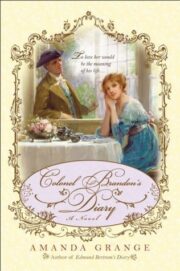

"Colonel Brandon’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Colonel Brandon’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Colonel Brandon’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.