I thought, If she looks so ill now, when she believes he is not a guest, how will she look when she learns that he was invited but did not come?

But no one enlightened her, for which I thank God, for I do not think she could have borne it.

And I — I can no longer bear it. Should I say something or should I remain silent? So much depends on whether she is engaged or not. If she is, I cannot speak, for she will not believe me. If not ...

Is there any hope for me? Is there a chance that I might yet win her?

Or must I resign myself to living without her?

I cannot sleep for thinking about it.

Tomorrow I must ask her sister and find out once and for all.

Friday 20 January

I rose early and was at Berkeley Street as soon as it was seemly.

I went in, and as soon as I did so, I saw the servant carrying a letter to Willoughby, addressed in Marianne’s hand.

I felt a cold wave wash over me. If they were openly corresponding, then there could be no doubt: they must be engaged.

Miss Dashwood greeted me kindly, but I could not concentrate on civilities, and I blurted out my thoughts, asking her when I was to congratulate her on having a brother and saying that news of her sister’s engagement was generally known.

‘It cannot be generally known,’ she returned in surprise, ‘for her own family does not know it.’

I was startled.

‘I beg your pardon,’ I said. ‘I am afraid my enquiry has been impertinent, but I had not supposed any secrecy intended, as they openly correspond, and their marriage is universally talked of. Is everything finally settled? Is it impossible to — ?’ And then I lost the last vestiges of my control and begged her, ‘Tell me if it is all absolutely resolved on; that any attempt — that in short, concealment, if concealment be possible, is all that remains.’

For I knew that if Marianne was indeed engaged, then I must endeavour to hide my own feelings and wish her happy.

Miss Dashwood hesitated before replying.

‘I have never been informed by themselves of the terms on which they stand with each other, but of their mutual affection I have no doubt,’ she said.

Their mutual affection. Nothing could have been plainer. I felt myself grow cold.

There was nothing left except for me to gather what remained of my dignity and to say, ‘To your sister I wish all imaginable happiness; to Willoughby that he may endeavour to deserve her.’

And then, unable to bear Miss Dashwood’s look of sympathy, I took my leave.

Their mutual affection.

The words rang in my ears.

It was worse than an engagement. An engagement might be ended, however unlikely that might be. But mutual affection ... I could not fight against that.

I had only one thing to fight against now, and that was despair.

Tuesday 24 January

I was disinclined for company this evening, but I could not sit at home and brood. I leafed through my invitations and set out for the Pargeters’ party, knowing that it would be well attended and that it would lift my spirits to be in company.

I saw some of my acquaintance there as I waited on the stairs to be received, which made the waiting tolerable. But on entering the drawing room, I received a shock, for there was Willoughby, and he was talking to a very fashionable young woman. From the way their heads were held close together, and the way he smiled at her, it was evident that she was no casual acquaintance, but that he was courting her.

But how could this be, when he was in love with Marianne?

‘Miss Grey is a lucky young woman, is she not?’ asked Mrs Pargeter, seeing the direction of my gaze. ‘Mr Willoughby is popular wherever he goes, and she has done well to catch him. They are well suited, fashionable people both, and with handsome fortunes, for though he has only a small income at present, he has expectations, and she is a considerable heiress with fifty thousand pounds. They make an attractive couple.’

‘A couple?’ I asked, with a peculiar feeling which was a mixture of elation and despair.

‘Yes, the marriage is to take place within a few weeks, and then they are to go to Combe Magna, his place in Somersetshire, where they intend to settle.’

I could not believe it, although why I could not, I did not know, for I had had every proof that he was not a gentleman. And yet this ... It was almost worse than what he had done to Eliza, for it was not thoughtless selfishness, it was wanton cruelty. He knew that Marianne was in town, for he had left his card and he must have received her letters. If he was really betrothed to Miss Grey, then why had he not written to Marianne and explained? It would have cost him nothing, demanded no sacrifice, as marriage to Eliza would have done. It would have taken him a few minutes, no more, and yet he had not even bothered to spend so small an amount of time to write to her and put her out of her misery.

He did not see me, for which I was grateful, for I could not have brought myself to acknowledge him. I was so sickened by his behaviour that I wanted to leave, but there was a crush of people coming up the stairs and it was impossible for me to force my way down them. I retired to the card room, therefore, to fume in silent rage, for it was evident that he had deserted Marianne as callously as he had deserted Eliza, with more cruelty, but — thank God! — to less ruinous effect.

After a few hands of cards I thought the crush would have abated and that I would be able to make my way down the stairs, and so I left the card-table and walked back into the saloon. As I entered it, my eye was drawn to a young woman just entering the room through the opposite door, and I saw that it was Marianne. She was looking very beautiful. Her eyes were bright and there was a spot of colour in each cheek which intensified her loveliness. Her dress was simple, but she needed no elaborate gown to set off her graceful figure. Her manner was animated and her gaze darted hither and hither, and I realized with dismay that she was looking for Willoughby.

At that moment she saw him, and her countenance glowed with delight. She began to move towards him, but her sister held her back, evidently fearing a scene, and guided her into a chair, where she sat in an agony of impatience which affected every feature as she waited for him to notice her.

At last he turned round and Marianne started up. Pronouncing his name in a tone of affection, she held out her hand to him. He approached, but slowly, and he addressed himself rather to Miss Dashwood than Marianne, talking to her as though they were nothing more than casual acquaintances, instead of intimate friends.

Marianne looked aghast.

‘Good God! Willoughby, what is the meaning of this?’ I heard her cry. ‘Have you not received my letters?’ And, as he stood with his hands resolutely behind his back, ‘Will you not shake hands with me?’

I saw him take her hand, but only because he could not avoid it, and heard him say, ‘I did myself the honour of calling in Berkeley Street last Tuesday, and very much regretted that I was not fortunate enough to find yourselves and Mrs Jennings at home. My card was not lost, I hope?’

The insolence! It was beyond anything. To speak to her in such a fashion, after the way he had behaved towards her at Barton!

She searched his eyes, as if unable to believe what was happening.

‘But have you not received my notes?’ she cried. ‘Here is some mistake, I am sure — some dreadful mistake. What can be the meaning of it? Tell me, Willoughby — for heaven’s sake, tell me, what is the matter?’

He made no reply; his complexion changed and all his embarrassment returned; but, on catching the eye of Miss Grey, he recovered himself again, and said, ‘Yes, I had the pleasure of receiving the information of your arrival in town, which you were so good as to send me.’

Then he turned hastily away with a slight bow and rejoined Miss Grey.

Marianne was white and stood as one stunned.

I thought, She is going to faint.

I stepped forward, but her sister was there before me and the carriage was sent for, and before very long she had left the house.

I did not linger. I was in no mood for entertainment after what I had just seen, and I was soon back at my club, where my heart was full of love and tenderness for Marianne and where I cursed the name of Willoughby.

Wednesday 25 January

I rose early, too restless to stay in bed, and went riding in the park. Having worked off the worst of my energy I went to Mrs Jennings’s house. I discovered that Marianne was resting, but I spoke to her sister and I soon found that they had learnt from Willoughby that he was engaged. He had written to Marianne pretending that he had never felt anything for her and saying that she must have imagined his regard. He had concluded by saying that he was engaged to Miss Grey and that they would soon be married.

‘That is abominable,’ I said. ‘Worse than I expected. And all this time he has let her suffer, knowing that his passion had cooled and that he had no intentions towards her.’

‘It is despicable, is it not?’ she said. ‘I would not have believed him capable of such a thing.’

‘He is capable of anything! And how is she?’

‘Her sufferings have been very severe: I only hope that they may be proportionably short. It has been, it is a most cruel affliction. Till yesterday, I believe, she never doubted his regard; and even now, perhaps — but I am almost convinced that he never was really attached to her. He has been very deceitful! ’

‘He has, indeed! But your sister does not consider it quite as you do?’

‘You know her disposition, and may believe how eagerly she would still justify him if she could.’

I wondered if I should tell her what I knew of Willoughby, but I did not know if it would bring her comfort or only distress her more, and in the end I left without speaking, to curse Willoughby and to love Marianne all the more.

Thursday 26 January

I was thinking over my dilemma this morning as I walked down Bond Street when I saw Mrs Jennings.

‘Well, Colonel! And what do you think of this business between Miss Marianne and Willoughby? I never was more deceived in my life. Poor thing! She looks very bad. No wonder. I can scarce believe it, but it is true. He is to be married very soon — a good-for-nothing fellow! I have no patience with him. Mrs Taylor told me of it, and she was told it by a particular friend of Miss Grey herself, else I am sure I should not have believed it; and I was almost ready to sink as it was. Well, said I, all I can say is that if it is true, he has used a young lady of my acquaintance abominably ill, and I wish with all my soul his wife may plague his heart out. And so I shall always say. I have no notion of men’s going on in this way: and if ever I meet him again, I will give him such a dressing down as he has not had this many a day. But there is one comfort, he is not the only young man in the world worth having; and with her pretty face she will never want admirers. There is a chance for you now, Colonel.’

Before I had a chance to reply, she went on, with scarcely a pause for breath.

‘Poor girl! She cried her heart out this morning, for a letter came from her mother and it was full of his perfections. Her mother, you see, believes them to be engaged. Ah, me! Miss Dashwood has a sad task before her, for she has to write to her mother and let her know how matters stand. Go to them, Colonel. You will do them good.’

My mind was made up. I would tell Marianne the truth. On arriving at the house I saw that Miss Dashwood, too, looked thinner than formerly; Willoughby’s perfidy was taking a toll on her as well as her sister.

‘I hope you do not mind me calling at such a time, but I met Mrs Jennings and she thought I would be welcome,’ I said. ‘I was the more easily encouraged to come because I thought that I might find you alone, which I was very desirous of doing. My object — my wish — my sole wish in desiring it — I hope, I believe it is — is to be a means of giving comfort — no, I must not say comfort — not present comfort — but conviction, lasting conviction to your sister’s mind. My regard for her, for yourself, for your mother — will you allow me to prove it, by relating some circumstances, which nothing but a very sincere regard — nothing but an earnest desire of being useful — though where so many hours have been spent in convincing myself that I am right, is there not some reason to fear I may be wrong?’

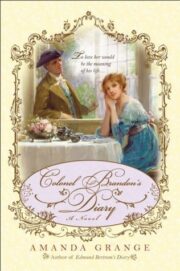

"Colonel Brandon’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Colonel Brandon’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Colonel Brandon’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.