“He doesn't to me. He hasn't said anything, but whenever he doesn't know I'm watching him, he looks depressed, or pensive, or just sad somehow. Or worried. I don't know what it is. Maybe he's unhappy at school.”

“You worry too much, Ollie,” he said, smiling at her, and then he leaned over and kissed her. “That was a good game. I had fun.”

“Yeah.” She grinned at him as he put an arm around her. “Because you won. You always say it was a good game when you win.”

“You beat me the last time we played squash.”

“Only because you pulled a hamstring. Without that, you always beat me. You play squash better than I do.” But she often beat him at tennis. It didn't really matter to her who won, she just liked being with him, even after all these years.

“You're a better lawyer than I was,” Harry said, and she looked startled. He had never said that to her before.

“No, I'm not. Don't be silly. You were a fantastic lawyer. What do you mean? You're just trying to make me feel better because you beat me at tennis.”

“No, I'm not. You are a better lawyer than I am, Ollie. I knew it even when you were a law student. You have a solid, powerful, meticulous way of doing what you do, and at the same time you manage to be creative about it. Some of what you do is absolutely brilliant. I admire your work a lot. I was always very methodical about my cases when I was practicing. But I never had the kind of creativity you do. Some of it is truly inspired.”

“Wow! Do you mean that?” She looked at him with gratitude and pleasure. It was the nicest compliment he had ever paid her about her work.

“Yes, I do. If I needed legal advice, I'd come to you in a hot minute. I'm not sure I'd want you as my tennis teacher. But as my lawyer, anytime.” She shoved him gently then, and he kissed her. She always had a good time with him. And she was pleased to see that he'd relaxed finally, after their battles about the ball. He still said he wasn't coming, but she hadn't mentioned it to him in a while. She wanted to let the subject cool off before she tried again.

They talked about Charlie again as they walked home. “I just have the feeling something is bothering him, but he doesn't seem to want to talk.”

“If you're right, he'll talk to you eventually,” Harry reassured her. “He always does.” He knew how close Olympia was to her older son, just as she was to the twins, and to Max. She was a terrific mother, and a wonderful wife. There was so much he admired about her and always had. Just as she loved and respected him. And he knew she had great instincts for her kids. If she thought something was upsetting Charlie, maybe she was right, although she felt more relaxed about it after discussing it with Harry. “Maybe he got his heart broken over some girl.” They both wondered if it was that. Charlie hadn't had a serious romance in a while. He went out a lot, and played the field. He hadn't had a serious girl in his life in nearly two years.

“I don't think it's that. I think he'd tell me if it was about a girl. It seems deeper than that to me. He just looks sad.”

“Working at the camp in Colorado will do him good,” Harry said as they reached their front door. They could hear both boys rough-housing as soon as they walked in. Charlie was playing cowboys and Indians with Max, and you could hear their bloodcurdling war whoops halfway down the block. Charlie had used toothpaste and her lipstick as war paint on his face, and the minute their mother saw them, she laughed. Max was running around the house, brandishing a toy gun at his older brother, wearing a cowboy hat and his underpants. Harry joined the fun, while Olympia went to make them all lunch. It had been a lovely morning.

But she grew more concerned again a few days later, when she got a bill from Dartmouth for counseling services. She mentioned it to Charlie discreetly, and he insisted he was fine. He told her a friend of his had committed suicide during second semester and it had upset him terribly at the time, but he was feeling better now. Hearing about it worried her, she didn't want him getting the same idea, and she remembered reading about kids who showed no sign of stress, and then committed suicide without warning. When she told Harry about it, he told her she was being neurotic, and reminded her that the fact that he had gotten counseling was a good sign. It was usually kids who didn't get therapy or counseling who went off the deep end. Charlie seemed fine to him. They played golf together over several weekends, and Charlie came down to have lunch at his office. He said he was thinking of going to divinity school after he graduated, and the ministry appealed to him. Harry was impressed by what he said, and the insights he had about people and delicate situations. Charlie broached the deb ball with him once or twice, and Harry refused to discuss it with him. He said that he disapproved of an event that excluded anyone, tacitly or otherwise, and he had taken a stand.

So had Veronica, but her position seemed to be softening by the time the girls left for Europe in July with their friends. Ginny had ordered a dress by then, a beautiful white taffeta strapless ballgown with tiny pearls sewn in a flower pattern in a wide border along the hem. It looked like a wedding gown, and Ginny was thrilled with it. And without saying anything to Veronica, Ginny and her mother had chosen a narrow white satin column with a diagonal band across one shoulder that looked like something Veronica would wear. It was sexy, sleek, and backless and would show off her slim figure. Ginny preferred her big ballgown. Both dresses were exquisite, and although the girls were identical, the dresses would set off the differences between them, and underline their contrasting styles. Olympia had hidden the satin dress in her closet and sworn Virginia to secrecy that they had shopped for it at all. And before they left for Europe, Ginny had posed in both dresses for the ball program. They didn't need to discuss it with Veronica at all. There were photographs of both girls now, or seemed to be. If she had a fit again later, they'd deal with it. For now, all was calm.

The girls were in good spirits when they left for Europe, and on good terms with each other. Charlie left for Colorado two days later, and Olympia and Harry left for their trip to France with Max. They had a wonderful time in Paris, went to every monument and museum, and took Max to the Jardin du Luxembourg. He had a ball playing with French children, and enjoyed all the rides. At night, they took Max out to bistros with them. He ate pizza, and steak with pommes frites. They went to Berthillon on the Île St. Louis for ice cream, and Max loved the crêpes they bought in the street in St. Germain. And they took him to the top of the Eiffel Tower. They had a wonderful trip, and in spite of Max sleeping in the adjoining room from them, Harry and Olympia had a romantic time. They stayed at a small hotel Harry knew on the Left Bank. And all three of them were sorry to leave Paris. On their last night, they had taken a long slow ride on a Bâteau Mouche on the Seine, admiring the lights of Paris and the beautiful buildings and monuments as they glided by.

After that, they went to the Riviera. They spent a few days in St. Tropez, a night in Monte Carlo, and a few days in Cannes. Max played on the beach, and started picking up a few words of French from a group of children his own age. At the end of a week, all three of them were rested, happy, and tanned. They had spent the whole week eating bouillabaisse, lobster, and fish. Max sent Charlie a T-shirt from St. Tropez, and Charlie sent them a steady stream of funny postcards, reporting on his adventures in camp. He seemed to be having a great time.

They were once again sad to leave, when Olympia, Harry, and Max flew from Nice to Venice to meet the girls. And all five of them had a terrific time in Venice. They visited every church and monument. Max fed the pigeons in the Piazza San Marco, and they all took a gondola ride under the Bridge of Sighs. Harry kissed Olympia as they passed under it, which the gondolier said meant they would belong to each other forever. As they kissed, Max scrunched his face up and the twins smiled at them and laughed at Max.

Their subsequent trip through northern Italy and into Switzerland was an unforgettable family time. They stayed at a beautiful hotel on Lake Geneva, traveled through the Alps, and wound up in London for the last few days. Max said he had loved all of it, and they all admitted that they were sad the twins were leaving for college. The house was going to be deadly quiet without them. On the flight back to New York, Olympia was quiet, wishing the girls wouldn't be leaving home so soon. The trip to Europe had been wonderful for all of them, but the last of the summer had flown past.

The twins' final days in New York were frantic before leaving for college—packing, organizing everything from computers to bicycles, and seeing all their friends. Ginny was excited to discover that several of her friends had accepted The Arches' invitation and were coming out with her. Veronica continued to pooh-pooh it, and then happened to see the photographs of Ginny in both dresses the day before they left for Brown, when she was looking for stamps in her mother's desk. She stood staring at the photographs for a long moment in outrage, with a look of astonished disbelief.

“How could you do that?” she railed at her mother, and accused her sister of lying to her, and finally Ginny broke down.

“Why should Mom pay both our tuitions because you want to make a statement and are willing to make Dad mad? It's just not fair to her.” Veronica had refused to visit Chauncey in Newport that summer, in protest of the position he'd taken. Ginny had dutifully gone there alone the weekend after they got home from Europe. “It's just not right. Why should Mom be punished because you won't do it?” Ginny had finally gotten under her skin, as had Harry's mother, who quietly took Veronica to lunch before they left, and asked her to be a good sport about it. And on her last night in New York, she agreed. Veronica swore she would hate doing it, and still disapproved of it violently, but her father's unreasonable position finally did it for her. She didn't want him to penalize their mother, so she grudgingly agreed. Olympia thanked her profusely, and promised to try and make it as painless as possible for her. Veronica tried on the dress and said she hated it, but it looked spectacular on her. She didn't have an escort yet, but promised to think about it. She had to give the committee his name by Thanksgiving.

“What about one of Charlie's friends?” Olympia suggested, and Veronica said she'd come up with someone herself. It was enough for now that she had agreed to do it, she didn't want to be bugged about her escort, so Olympia backed off. The only remaining protester was Harry, who refused to even discuss the matter with her. He was disappointed that Veronica had conceded, but given her father's manipulative and punitive position, he agreed that it had been the decent thing for her to do, for her mother's sake. But there was no penalty for his not attending. He refused to reconsider, and said nothing on earth could make him go. He was incredibly stubborn about it, and insisted it was a matter of principle. Charlie attempted to broach the subject with him before he left for his senior year at Dartmouth, and Harry changed the subject whenever Charlie mentioned it. It was clear to everyone, including Max, that Harry wouldn't go. Despite the wonderful time they had shared in Europe, Harry hadn't mellowed a bit about the ball.

Olympia and Charlie had lunch together on his last weekend at home, and he seemed relaxed and happy after the summer. He seemed more at ease in his own skin than he had in June, and she was no longer worried about him. He was busy with his friends in the city, said he was looking forward to the school year, and planning to apply to divinity school that fall. He was also talking about doing graduate studies at Oxford, or taking a year off and traveling, or maybe taking a job he'd been offered in San Francisco, working for his roommate's father. He hadn't made his mind up yet about his many options, all of which sounded reasonable to his mother and Harry. She felt sorry for him at times, he seemed so young. It was so hard to make definitive life choices and the right decisions. He was a responsible boy, and a good student, everyone he met liked him. He was thinking about a teaching job, too. He was all over the map.

“Poor kid, I'd hate to be young again,” Olympia commented to Harry the day she'd had lunch with Charlie. “He's feeling pulled in about four hundred directions. His father wants him to come to Newport and train polo ponies with him. Thank God that's not one of the options he's considering.” Nor was working in Chauncey's family's bank in New York. He had decided against it. Charlie wanted to do something different, he just hadn't figured out what yet. Harry thought he should go to Oxford. Olympia liked the sound of the job in San Francisco. And Charlie himself wasn't sure. Harry had also suggested law school, which Charlie had resisted. He still liked the idea of divinity school best of all. “I can't see him as a minister,” Olympia said honestly, although he was religious, more so than the rest of the family.

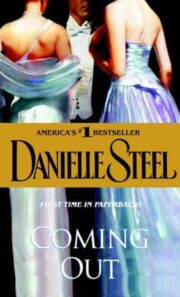

"Coming Out" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Coming Out". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Coming Out" друзьям в соцсетях.