"And what?"

"He's your husband, Kristin. You have to remember that. You married him. He's your husband now."

"I'll give him a chance to explain," was all that Kristin said. She would give him a chance. But when? He was gone, and winter was coming, and she didn't know when she would see him again.

Two days later Pete and the hands returned from the cattle drive, and Jamie and Malachi prepared to ride back to the war. Kristin was sorry she had argued with Malachi, and she hugged him tightly, promising to pray for him. She kissed Jamie, and he assured her that since his unit was stationed not far away he would be back now and then to see how she and Shannon were doing.

Shannon kissed Jamie — and then Malachi, too. He held her for a moment, smiling ruefully.

Then the two of them rode away.

Kristin stood with Shannon at her side, and they watched until they could no longer see the horses. A cool breeze came up, lifting Kristin's hair from her shoulders and swirling around her skirts. Winter was on its way. She was very cold, she realized. She was very cold, and she was very much alone.

CHAPTER ELEVEN

Winter was long, hard and bitterly cold. In December Shannon turned eighteen and in January Kristin quietly celebrated her nineteenth birthday. They awaited news from the front, but there was none. The winter was not only cold, it was also quiet, ominously quiet.

Late in February, a Union company came by and took Kristin's plow mules. The young captain leading the company compensated her in Yankee dollars which, she reflected, would help her little when she went out to buy seed for the spring planting. The captain did, however, bring her a letter from Matthew, a letter that had passed from soldier to soldier until it had come to her.

Matthew had apparently not received the letter she had written him. He made no mention of her marriage in his letter to her. Nor did he seem to know anything about Zeke Moreau's attack on the ranch after their father's murder.

It was a sad letter to read. Matthew first wrote that he prayed she and Shannon were well. Then he went into a long missive on the rigors of war — up at five in the morning, sleeping in tents, drilling endlessly, in the rain and even in the snow. Then there was an account of the first major battle in which he had been involved — the dread of waiting, the roar of the cannons, the blast of the guns, the screams of the dying. Nightfall was often the worst of all, when the pickets were close enough to call out to one another. He wrote:

We warn them, Kristin. "Reb! You're in the moonlight!" we call out, lest our sharpshooters take an unwary lad. We were camped on the river last month; fought by day, traded by night. We were low on tobacco, well supplied with coffee, and the Mississippi boys were heavy on tobacco, low on coffee, so we remedied that situation. By the end of it all we skirmished. I came face-to-face with Henry, with whom I had been trading. I could not pull the trigger of my rifle, nor lift my cavalry sword. Henry was shot from behind, and he toppled over my horse, and he looked up at me before he died and said please, would I get rid of his tobacco, his ma didn't know that he was smoking. But what if you fall? he asks me next, and I try to laugh, and I tell him that my ma is dead, and my pa is dead, and that my sisters are very understanding, so it is all right if I die with tobacco and cards and all. He tried to smile. He closed his eyes then, and he died, and my dear sisters, I tell you that I was shaken. Sometimes they egg me on both sides— what is a Missouri boy doing in blue? I can only tell them that they do not understand. The worst of it is this — war is pure horror, but it is better than being at home. It is better than Quantrill and Jim Lane and Doc Jennison. We kill people here, but we do not murder in cold blood. We do not rob, and we do not steal, nor engage in any raping or slaughter. Sometimes it is hard to remember that I was once a border rancher and that I did not want war at all, nor did I have sympathy for either side. Only Jake Armstrong from Kansas understands. If the jayhawkers robbed and stole and murdered against you, then you find yourself a Confederate. If the bushwhackers burnt down your place, then you ride for the Union, and the place of your birth doesn't mean a whit.

Well, sisters, I do not mean to depress you. Again, I pray that my letter finds you well. Kristin, again I urge you to take Shannon and leave if you should feel the slightest threat of danger again. They have murdered Pa, and that is what they wanted, but I still worry for you both, and I pray that I will get leave to come and see you soon. I assure you that I am well, as of this writing, which nears Christmas, 1862. I send you all my love. Your brother, Matthew.

He had also sent her his Union pay. Kristin fingered the money, then went out to the barn and dug up the strongbox where she kept the gold from the cattle sales and the Yankee dollars from the captain. She added the money from Matthew. She had been feeling dark and depressed and worried, but now, despite the contents of Matthew's letter, she felt her strength renewed. She had to keep fighting. One day Matthew would come home. One day the war would be over and her brother would return. Until then she would maintain his ranch.

By April she still hadn't been able to buy any mules, so she and Samson and Shannon went out to till the fields. It was hard, backbreaking labor, but she knew that food was growing scarcer and scarcer, and that it was imperative that they grow their own vegetables. Shannon and she took turns behind the plow while Samson used his great bulk to pull it forward. The herd was small, though there would be new calves soon enough. By morning Kristin planned the day with Pete, by day she worked near the house, and supper did not come until the last of the daylight was gone. Kristin went to bed each night so exhausted that she thought very little about the war.

She didn't let herself think about Cole, though sometimes he stole into her dreams uninvited. Sometimes, no matter how exhausted she was when she went to bed, she imagined that he was with her. She forgot then that he had been one of Quant rill's raiders. She remembered only that he was the man who had touched her, the man who had awakened her. She lay in the moonlight and remembered him, remembered his sleek-muscled form walking silent and naked to her by night, remembered the way the moonlight had played over them both…

Sometimes she would awaken and she would be shaking, and she would remind herself that he had ridden with Quantrill, just like Zeke Moreau. She might be married to him now, but she could never, never lie with him again as she had before. He was another of Quant rill's killers, just like Zeke. Riding, burning, pillaging, murdering — raping, perhaps. She didn't know. He had come to her like a savior, but Quant rill's men had never obeyed laws of morality or decency. She wanted him to come back to her because she could not imagine him dead. She wanted him to come back to her and deny it all.

But he could not deny it, because it was the truth. Malachi had said so. Malachi had known how the truth would hurt, but hadn't been able to lie. There was no way for Cole to come and deny it. There was just no way at all.

Spring wore on. In May, while she was out in the south field with Samson, Pete suddenly came riding in from the north pasture. He ignored the newly sown field, riding over it to stop in front of Kristin.

"He's back, Miz Slater, he's back. They say that Quantrill is back, and that Quantrill and company do reign here again!"

• • •

The house was still a long way off when Cole reined in his horse and looked across the plain at it. Things looked peaceful, mighty peaceful. Daisies were growing by the porch, and someone — Kristin? Shannon? — had hung little flowerpots from the handsome gingerbread on the front of the house.

It looked peaceful, mighty peaceful.

His heart hammered uncomfortably, and Cole realized that it had taken him a long time to come back. He didn't know quite why, but it had taken him longer than necessary. He hadn't been worried at all, at least not until he had heard that Quantrill was back. He didn't understand it. All through the winter, all through the early spring, he'd had dreams about her. He had wanted her. Wanted her with a longing that burned and ached and kept him staring at the ceiling or the night sky. Sometimes it had been as if he could reach out and touch her. And then everything had come back to him. The silky feel of her flesh and the velvety feel of her hair falling over his shoulders. The startling blue of her eyes, the sun gold of her hair, the fullness of her breasts in his hands…

Then, if he was sound asleep, he would remember the smell of smoke, and he would hear the sound of the shot, and he would see his wife, his first wife, his real wife… Running, running… And the smoke would be acrid on the air, and the hair that spilled over him would be a sable brown, and it would be blood that filled his hands.

It hurt to stay away. He needed her. He wanted her, wanted her with a raw, blinding, burning hunger. But the nightmares would never stay away. Never. Not while his wife's killer lived. Not while the war raged on.

He picked up the reins again and nudged his mount and started the slow trek toward the house. His breath had quickened. His blood had quickened. It coursed through him, raced through him, and it made him hot, and it made him nervous. Suddenly it seemed a long, long time since he had seen her last. It had been a long time. Almost half a year.

But she was his wife.

He swallowed harshly and wondered what his homecoming would be like. He remembered the night before he had left, and his groin went tight as wire and the excitement seemed to sweep like fire into his limbs, into his fingertips, into his heart and into his lungs.

They hadn't done so badly, he thought. Folks had surely done worse under the best of circumstances.

When the war ended…

Cole paused again, wondering if the war would ever end. Those in Kansas and Missouri had been living with the skirmishing since 1855, and hell, the first shots at Fort Sumter had only been fired in April of '61. Back then, Cole thought grimly, the rebels had thought they could whomp the Yankees in two weeks, and the Yankees had thought, before the first battle at Manassas, it would be easy to whip the Confederacy. But the North had been more determined than the South had ever imagined, and the South had been more resolute than the North had ever believed possible. And the war had dragged on and on. It had been more than two years now, and there was no end in sight.

So many battles. An Eastern front, a Western front. A Union navy, a Confederate navy, a battle of ironclads. New Orleans fallen, and now Vicksburg under siege. And men were still talking about the battle at Antietam Creek, where the bodies had piled high and the corn had been mown down by bullets and the stream had run red with blood.

He lifted his hands and looked at his threadbare gloves. He was wearing his full dress uniform, but his gold gloves were threadbare. His gray wool tunic and coat carried the gold epaulets of the cavalry, for though he was officially classified a scout he'd been assigned to the cavalry and was therefore no longer considered a spy. It was a fine distinction, Cole thought. And it was damned peculiar that as a scout he should spend so much of his time spying on both sides of the Missouri-Kansas border. He wondered bleakly what it was all worth. In January he'd appeared before the Confederate Cabinet, and he'd reported honestly, as honestly as he could, on the jayhawkers' activities. Jim Lane and Doc Jennison, who had led the jayhawkers — the red-legs as they were sometimes known because of their uniforms — were animals. Jim Lane might be a U.S. senator, but he was still a fanatic and a murderer, every bit as bad as Quantrill. But the Union had gotten control of most of the jayhawkers. Most of them had been conscripted into the Union Army and sent far away from the border. As the Seventh Kansas, a number of jayhawkers had still been able to carry out raids on the Missouri side of the border, plundering and burning town after town, but then Major General Henry Halleck had ordered the company so far into the center of Kansas that it had been virtually impossible for the boys to jayhawk.

As long as he lived, Cole would hate the jayhawkers. As long as he lived, he would seek revenge. But his hatred had cooled enough that he could see that there was a real war being fought, a war in which men in blue and men in gray fought with a certain decency, a certain humanity. There were powerful Union politicians and military men who knew their own jayhawkers for the savages they were, and there were men like Halleck who were learning to control them.

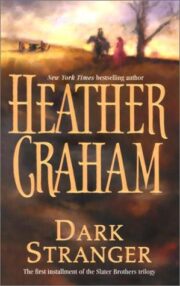

"Dark Stranger" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Dark Stranger". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Dark Stranger" друзьям в соцсетях.