The next day Roderick went off early. It continued to rain during the morning and cleared up after luncheon, which we took in our rooms. I was glad of that. I did not want to have to face Lady Constance alone.

I was wondering what she would say to Fiona and what Fiona’s response would be. Fiona could be forthright. The outcome would be interesting to me, because in a way Fiona’s case was not unlike my own.

It was my custom to call on Fiona in the afternoon. I very much wanted to hear the result of the interview and I must delay my visit until it was over.

I had seen Lady Constance set out after luncheon. She was walking the short distance from the house to the site. She looked brisk as she set out, as though she were going into battle. She carried a black umbrella. It was not raining at the time, but there could well be another shower or two.

I guessed the meeting would be brief.

I should hear all about it from Fiona. An hour passed while I sat at my window, waiting for the return of Lady Constance. I was surprised that she was so long. The walk would be about fifteen minutes there and fifteen back. An hour had passed. What could they be talking about for the rest of the time?

Could I have missed her return? That was hardly likely. It might be that she had gone on somewhere else. That was not likely, but I supposed just possible.

It was half an hour later when I decided I would call on Fiona. Lady Constance must have left by now and if by some chance she had not done so, I should have to make some excuse and come away.

I put on my outdoor clothes with stout walking shoes and took an umbrella with me.

It was a somewhat bleak day and the countryside looked a little desolate. Everything was damp and there was rain in the air, although it was not actually falling. There was scarcely any wind and dark clouds loured low in the sky.

When I came near the site, it started to rain. I put up my umbrella and took the path which led up to the cottage.

It looked different. There were pieces of loose earth spattered about. They must have been disturbed by the heavy rains, I thought.

I glanced over at the baths and the mosaic floor. They looked just as usual. Then … too late … I saw the yawning gap before me. I tried to stop sharply, but as I did so, the ground beneath me gave way. I tripped forward, my umbrella flew away and I was falling … down into darkness.

I was stunned and bewildered for a few seconds before I realized what was happening. This was one of the spots Roderick had talked about. The soil was giving way beneath my feet. It was in my eyes. I shut them tightly for a few seconds. I tried to clutch at something, but the damp earth came away in my hands.

My fall was not rapid. It was impeded by the obstructing soil which gave way under my weight. And then … suddenly I was falling no longer. I opened my eyes. I could not see much, but the hole through which I had fallen was still there and it let in a little light.

I was standing on something hard. I felt a mild relief because I was no longer falling.

I was able to put my hand down and touch what I was standing on. It was smooth and felt like stone. Fragments of soil were still falling round me and onto the shelf on which I was standing. I listened to the sound of their fall. It was now intermittent and I saw that the hole through which I had fallen remained, so there was still a little light from above coming in.

I felt a great relief. At least I was not entirely buried. Someone must come. But who? They would discover that the land had subsided. But how long could I stay here?

I perceived that it would be impossible to try to climb up. There was nothing but damp loose earth to cling to. Then I began to feel very frightened.

I heard something. A cry. “Help … help me …”

“Hello,” I said. “Hello.”

“Here … here …”

I recognized Lady Constance’s voice.

A thought flashed into my mind. It had happened to her. She had been going to call on Fiona, just as I had been. She would have taken the same path.

“Lady Constance,” I gasped.

“Noelle. Where … are you here?”

“I fell …”

“As I did. Can you move?”

“I … I’m afraid to. It might …”

I had no need to explain. She was in the same position as I was. At the moment we were safe … but how did we know whether the slightest movement might set the earth falling down on us, burying us alive?

My eyes had grown accustomed to the darkness. I appeared to be on some sort of stone floor. There was earth scattered all over it. I could see something dark … a shape moving slightly. It was Lady Constance.

“Can you move very slowly … this way?” I said. “We seem to be in some sort of cave. It’s lighter where I am. The hole is still above. I’m afraid to move because the earth round me is very loose. But there seems to be a sort of ceiling.”

She started to crawl slowly towards me. There was a sound of falling earth. I held my breath. I was desperately afraid that the soil would fall in and bury us.

I said: “Wait … wait.”

She obeyed and all was quiet. I said: “Try again.”

She was close now. I could see her vaguely.

She put out a hand and touched my arm. I grasped her hand.

I could sense that her relief matched mine.

“What … what can we do?” she whispered.

“Perhaps they’ll come and rescue us,” I said.

She did not speak. “Are you all right?” I asked.

“My foot hurts. I’m glad you’re here. I shouldn’t be. But … it makes two of us.”

“I understand,” I said. “I’m glad you’re here.”

We were silent for a while, then she said: “This is the end of us perhaps.”

“I don’t know.”

“What can happen, then?”

“We’ll be missed. When Roderick comes back. Someone will come to look for us. We must keep very still. We must not disturb anything. When they miss us they’ll come to rescue us.”

“You’re trying to comfort me.”

“And myself.”

She laughed, and I laughed with her. It was quite mirthless laughter, a defence, perhaps, against fate.

“Strange,” she said, “that you and I should be here.”

“Very strange.”

“It’s good to talk, isn’t it? I feel so much better now. I thought I was going to die alone. I was very frightened.”

“It’s always good to share something, I suppose … even this.”

“It’s a help. Do you really think we shall get out of this?”

“I don’t know. I think we may have a chance. Someone might come along.”

“They might fall down with us.”

“They might see what has happened in time. They’d get help.”

“Should we call out?”

“Would they hear us?”

“If we heard them, they might hear us. There’s a gap there. You can see the daylight.”

“While that’s there, there is hope.”

“You’re a sensible girl,” she said. “I’m afraid I haven’t been very good to you.”

“Oh … that’s all right. I understand.”

“You mean about Charlie and your mother?”

“Yes.”

We were silent for a few moments. She was still holding my hand. I think she was afraid something would happen to separate us. I, too, felt comforted by her closeness.

She said: “Let’s talk. I feel better talking. I know what happened about the bust.”

“The bust?”

“On the stairs. I know Gertie broke it and you took the blame.”

“How?”

“I was watching from the top landing. I saw the whole thing. Why did you do it?”

“Gertie was terrified of being sent away. She sends money home to her family. She was afraid you would dismiss her and wouldn’t give her a reference. It seemed the simplest thing to do.”

“I see. That was good of you.”

“It was nothing much. I was going away soon. It seemed better to let you think it was my fault.”

“How did you know all this about Gertie?”

“We talk. She tells me about her family.”

“You talk thus … to the servants?”

“I suppose that shocks you. I was brought up in a different way … where differences in class were not nearly so important as human relationships. People were people in our household, not servants and employers.”

“That was Desiree, was it?”

“Yes. She was like that. She was friendly with everyone.”

“And you take after her.”

“No. I’m afraid there was only one Desiree.”

Silence again. I thought it was a pity the subject of my mother should be brought up at a time like this.

But she was still holding my hand.

It was not good to be silent. It made us frighteningly conscious of our desperate plight.

“I had no idea that you knew about the bust,” I said.

“I was watchful.”

“Of me?”

“Yes, of you.”

“I was aware of it.”

“Were you? You gave no sign. I can’t tell you how glad I am that you fell down where I did. I’m a very selfish woman.”

“No … no. I understand. I am glad you are here.”

She laughed and moved closer to me.

“Strange, is it not? We must keep talking, mustn’t we? When we talk, fear seems to recede … but it’s there. I think we may be going to die.”

“I think there is a good possibility of rescue.”

“You say that to comfort me.”

“As I told you, I also say it to comfort myself.”

“Are you afraid of dying?”

“I had never thought of it till now. One seems to be born with the idea that one will go on forever. One can’t imagine a world without oneself.”

“That’s called egoism, isn’t it?”

“Yes, I suppose so.”

“So you have never had to be afraid until this happened?”

“That is so. I’m afraid now. I know that at any moment the earth can fall in and bury us.”

“We shall be buried together. Does that comfort you?”

“Yes, it does.”

“It comforts me, too. It is strange that I should draw comfort from you when I think how I resented your coming to Leverson.”

“I am sorry. I should never have come.”

“I’m glad you did now.”

I laughed. “Because if I had not, I could not have joined you here.”

“Yes … just that.” She laughed with me. Then she said: “Well, there is something more. We are in this strange position and down here we are getting to know each other more than we ever would in an atmosphere of security.”

“It is because we are facing possible death. That must draw people close.”

“Let’s go on talking,” she said.

“I am listening, too,” I said. “If we hear anything from above, we must be ready to call … to let them know we are here.”

“Yes. Could we hear them?”

“I don’t know. I think we might.”

“But let’s go on talking … softly. I can’t bear the silence.”

“Are you comfortable?”

“My foot hurts.”

“I expect you have strained something.”

“Yes. It’s a small thing when one may be facing death.”

“Don’t think of that.”

“I’ll try not to. You found my book of cuttings. You looked at them with Gertie.”

“I’m sorry. She called me in and when I saw … it was irresistible.”

“What did you think of it?”

“I thought it was very sad.”

“Why?”

“Because it told me how you must have felt through all those years.”

“I knew everything she was playing in … what they said about her. I understood it all. He was besotted about her.”

“Other people were, too.”

“She must have been a wonderful person.”

“To me she was the most wonderful person in the world.”

“A good mother, was she?”

“The best.”

“That seems unlikely. A woman like that! What would she know about bringing up children?”

“She knew about love.”

Silence again. I realized she was weeping quietly.

“Tell me more about her.”

So I told her. I told her how Dolly came with his plans and how they quarrelled and abused each other. I told her about all the dramas, the last-minute changes, the first-night nerves.

It was like a dream … sitting in a dark hole with Lady Constance, talking of my mother. But it helped me as it did her, and at that time we were overwhelmed with gratitude for the other simply for being there.

I thought: If we ever get out of here, we shall be friends. We can’t go back to our old relationship after this. Each of us has shown the other too much of our inner selves.

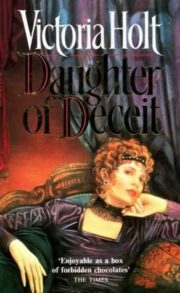

"Daughter of Deceit" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Daughter of Deceit". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Daughter of Deceit" друзьям в соцсетях.