“Oh, Gertie …”

She rushed to me and flung her arms round my neck. We hugged each other for a few moments.

“I’m that glad you’re safe, miss, I’m forgetting my place. You’re safe and sound and I had a part in bringing you back. Now, can I get you something to eat? Some coffee … some toast?”

“Just that, Gertie, and some hot water. I’m longing to get up.”

“I’ll see to it,” she said.

I lay back in bed, marvelling at what I had heard and wondering if it could possibly be true.

I hastily washed and dressed and ate a little breakfast. I must admit I felt light-headed, but that was due to everything which had happened in such a short time rather than any physical disability.

My mind was a jumble of memories: those horrifying moments when I had fallen, my conversation with Lady Constance, the rescue, all that Gertie had told me—and all dominated by Roderick’s telling me he loved me.

More than anything I wanted to see Roderick.

When I was ready to go down, I went to the window, and there he was, seated on the wicker seat, looking up at my window. He saw me immediately.

“I’m coming down now,” I called.

I ran out of the room and down the stairs. He was striding towards me, taking my hands in his.

“Noelle … how are you this morning? It’s wonderful to see you! I have been sitting here … waiting … since Gertie told me you were going to get up.”

“I wanted so much to talk to you.”

“And I to you. Did you sleep well?”

“I knew nothing since I took the doctor’s sedative and woke to find the sun streaming into my room.”

“I’ve had nightmares … dreaming that we couldn’t get you out.”

“Well, forget them, because here I am.”

“And you are always going to be here, Noelle. Let’s sit down and talk. I love you, Noelle … so much. I’ve been wanting to tell you for a long time. I was afraid it was too soon … your mother was so recently dead, and I knew you were still living with your grief. I was afraid you could not think of anything else. I told myself I must wait until you had recovered a little. But yesterday it came out. I couldn’t stop it.”

“I’m glad.”

“Does that mean you love me, too?”

I nodded and he put his arm round and tightened his hold on me.

“We shan’t want a long engagement,” he said. “My father will be pleased. He’ll see it as a way of keeping you here.”

“I’m so suddenly happy,” I said. “I never thought to feel like this again. It all looked so grim. I hated being in London. There were so many memories of her … and I was away from you. Then you came and it was bearable. I was wondering what I should do … and now there is a chance to be happy again.”

“We certainly shall be.”

“What of your mother? Have you heard how she is this morning?”

“Still sleeping. She is very shocked. She will need a long rest.”

“She has other plans for you.”

He laughed. “Oh,” he said. “Marriage. She will come round when she sees it’s inevitable. Don’t think of obstacles. There are not going to be any … and if there are, we shall quickly overcome them.”

“I’m thinking about it all the time.”

He kissed my hair gently. I thought: How can I be so suddenly happy? Yesterday was so different. Today I am in another world … and all because yesterday I nearly lost my life. The birds were singing more gaily; the grass glistened with tiny globules of morning dew; the flowers were more colourful and fragrant because of the recent heavy rain: the whole world had become more beautiful because I was happy.

For a few moments we were silent. I believe he, as I, was savouring the beauties of nature around us while we thought of the future which would be ours.

I said at length: “Gertie told me a strange story this morning.”

“Yes,” he said. “About Kitty the maid and Mrs. Carling.”

“Is it true, then?”

“That she took the sign away? It seems so. Tom Merritt had put it up during the morning with four or five others in those places he considered to be dangerous. It was warning people not to use those parts until someone could get to work to test their safety.”

“Gertie said that Kitty saw her take it away and didn’t know what she ought to do about it.”

“Yes, that’s so. It had certainly been removed. Kitty saw her do it. These people watch what goes on and Mrs. Carling knew … and so did Kitty … that you often went to the cottage in the afternoons. So Kitty waited and saw you fall. She didn’t know what she ought to do, but she eventually told Gertie. Thank God she did. We should have found you eventually, but she helped us get there more quickly.”

“Do you think Mrs. Carling really did take the sign away?”

“She is mad, you know. We have suspected that for some time. Fiona was very worried about her strange behaviour … which was getting worse. She has always been fanciful … eccentric … but this was different. Fiona has had a terrible time looking after her. Mrs. Carling has been taken to a hospital for the mentally unstable. She was caught trying to set fire to the cottage again. Thank God that maid of hers finally had the good sense to come to Gertie. That helped us get you out without the delay there might have been. I can’t stop thinking of what might have happened. You could so easily …”

I said: “We were fortunate to have landed on a kind of ledge.”

“A ledge?”

“It seemed like stone of some sort. Otherwise we could have gone right down. The earth was so damp and soggy. I am glad I was near your mother. I want to see her as soon as I’m allowed to. Do you think I shall be able to?”

“But of course. We’ll go together and tell her …”

“Oh … no. She shouldn’t have another shock so soon. Roderick, will you leave it to me … just for a while? I think it may be possible that I could explain it to her.”

“Don’t you think it would be better to come from me?”

“I should have thought so … but after yesterday … well, we were together down there all that time … not knowing whether we should ever come up. That sort of thing does something to you. I think it may have done to your mother …”

“If you think it is best.”

“Perhaps I’m wrong. It is different here in the house from what it is in a damp dark hole which can collapse on you at any moment.”

“It will be all right. When she sees how pleased my father will be …”

I was unsure, but I could not let anything cloud my happiness at that moment. I wanted to savour every minute. Nothing must stand in the way of my happiness.

The doctor called later that morning. He saw me in my room and told me that he thought I had recovered from my shock. The bruises would in time disappear and I had clearly not broken any bones, which was a mercy. We had been lucky to have been rescued comparatively quickly. He thought I should not allow myself to become exhausted and that I should remember I had been through a very trying experience. Apart from that, I might carry on as normal.

He was a little longer with Lady Constance. She, too, had emerged from the accident with a good deal of luck. She must undoubtedly rest on account of her ankle alone, and she must keep to her room for a while. He hoped that shortly she would be none the worse for what she had endured.

When I asked if I might be allowed to see her, he said: “Certainly. A little chat will do her good. She doesn’t want to be made to feel she’s an invalid. Just remember that a shock like that can have an effect which may not be immediately apparent.”

So I went to see Lady Constance.

She was sitting up in bed, looking very different from when I had last seen her. Her hair was neatly drawn away from her face to make a coil on the top of her head, and she was dressed in a negligee of pale blue. As I entered the room, I had the feeling that she had left my companion of misfortune far behind and had reverted to the familiar and formidable mistress of the household who had intimidated Gertie and—I had to admit—myself.

I approached the bed. I knew she was trying to make a barrier between us, struggling to return to that haughty arrogance which had been her shield.

“How are you, Noelle?” she said coolly.

“I am well enough, thank you. And you, Lady Constance?”

“Rather shaken still, and my ankle is painful. Otherwise, apart from feeling tired, I am all right.”

Her eyes held mine for a moment. I guessed she was remembering and regretting those confidences. Was she debating whether they could be set aside, forgotten? No. That could hardly be. Could they be put down to the somewhat hysterical ramblings of someone who was face to face with possible death? She was a proud woman and, now that she had returned to the safety of everyday life, she would be remembering, and resenting afresh, the indignities and humiliation she had suffered through her husband’s infatuation for another woman.

“It was a terrible ordeal we suffered,” she began, paused, and then added: “Together.”

“It was a comfort to have someone to share it with,” I said.

“A comfort indeed.”

I saw the tears on her cheeks then, and I knew that the battle with herself was nearly over. Boldly I went closer to the bed and I took both her hands.

“It was indeed a terrible ordeal,” I repeated, “and yet I cannot be entirely sorry that it happened.”

She was silent.

I went on: “To talk together … to understand …”

“I know,” she said with emotion. “I know …”

I realized then that it was for me to take the initiative. Her pride was holding her back.

“I hope,” I said, “that, now we have found friendship, we are not going to lose it.”

She gripped my hand and replied quietly: “I hope that, too.”

The barriers were down. It was as though we were back together in that dark and dismal hole.

She took a handkerchief from under her pillow and wiped her eyes. “I am being foolish,” she said.

“Oh no … no.”

“Yes, my dear Noelle. We shall always remember what we went through together, but, as you say, there is some good in everything. And it has made us friends.”

“I was afraid it was just for then. I was afraid it would not last.”

“It became too firm for that … even in that short time. But it was not exactly so sudden. I have always admired you … just as I did … her.”

“We shall start from now,” I said. “The rest is in the past. It is the present which is important. I feel happier and hopeful now.”

She did not ask for explanations, and I think because she was afraid of showing more emotion, she said: “You have heard that that madwoman removed the warning sign.”

“Yes.”

“They have put her away. It was she who set fire to the cottage. What a danger she was!”

“Yes,” I replied. “It was fortunate that Kitty, the maid, saw what she had done.”

“The poor child is a little retarded.”

“But sufficiently aware to tell Gertie what she had seen.”

“She can’t go back, of course. We shall keep her here. I wonder what Fiona Vance will do now.”

“It will be a relief to her, I expect, to know that her grandmother is being cared for. I fancy she was something of a trial to her and must have been for some time. She never mentioned it or complained.”

“I daresay something will be arranged.”

We were silent for a few seconds, then Lady Constance said: “My husband will be home soon, I daresay.”

I made a hasty decision.

“Lady Constance,” I said, “there is something I want to say to you. I don’t know how you will take this. If I don’t tell you now, Roderick will soon. But if it is going to upset you …”

“I think I know what it is,” she said. “Roderick wants to marry you. That is it, is it not?”

I nodded.

“And,” she went on, “you want to marry him. I have seen it coming.”

“And you, Lady Constance?”

She lifted her shoulders, and I went on: “I know you expected your son to marry someone very different from me. I know you wanted the highest in the land for him …”

She did not reply for some moments. When she spoke, it was almost as though she were talking to herself.

“I am not a very happy woman. For years I have brooded. All those years my husband was with her. She was everything that I was not, the sort of person a man can be at peace with … happy with … the sort who doesn’t make demands. I realize now that was something I was doing constantly … trying to make people what they were not … to fit in with what I wanted them to be. I sought the wrong things in life. When we were in that dark hole, I saw things which I had never seen before. It was as though a light had been thrown on the past, and I began to ask myself how much of what had happened had been due to myself. If I had been different … loving … lighthearted … not setting such store by material things … perhaps it would have been different. I saw clearly your care for Gertie … your love for your mother. I began to see that I had made misjudgements, set too much store on the less important aspects of life. I saw how foolish I had been to dislike you because you were your mother’s daughter … because you had not such a grand pedigree as I have. Noelle, I shall be grateful to you always. I shall be happy to continue our friendship through our lives, and I hope you will never go away from this house.”

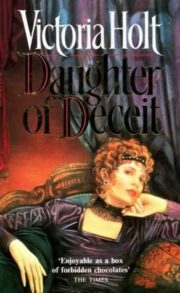

"Daughter of Deceit" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Daughter of Deceit". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Daughter of Deceit" друзьям в соцсетях.