“Is that Madame Gamier still looking after you?” asked Angele.

“Oh yes, she is.”

“The kitchen floor needs cleaning. What does she do here?”

“Dear old Garnier. She has a wonderful face.”

“Have you been painting her?”

“Of course.”

“I think she is quite repulsive.”

“You do not see the inner woman.”

“So, instead of cleaning … she has been sitting for you?”

He turned to me. “You were saying that you wished to see some of my pictures. I will begin with Madame Garnier.”

He took one of the canvasses and set it on an easel. It was the portrait of a woman—plump, merry, with a certain shrewdness about her mouth and more than a touch of cupidity in her eyes.

“It’s certainly like her,” said Angele.

“It’s very interesting,” I said. Gerard was watching me intently. “One feels one knows something about her.”

“Tell me what,” said Gerard.

“She likes a joke. She laughs a great deal. She knows what she wants and she is going to get it. She is somewhat cunning and is going to make sure she gets more than she gives.”

He was smiling at me, nodding his head.

“Thank you,” he said. “You have paid me a very nice compliment.”

“Well,” said Angele, “I have no doubt it suits Madame Gamier very well to sit in a chair smirking instead of getting on with her work.”

“And it suits me very well, Maman. “

I said: “You promised to show us more of your pictures.”

“I feel less reluctant after your verdict on this one.”

“Surely you have no doubts of your work,” I said. “I should have thought an artist must have complete belief in himself. If he does not, will anyone else?”

“What words of wisdom!” he said with a touch of mockery. “Well, here we are. This is the concierge. And here is a model whom we use sometimes. A little conventional, eh? Here is Madame la concierge. Too accustomed to sitting … not quite natural.”

I thought his work very interesting. He showed us some scenes of Paris. There was one of the Louvre and another of the Tuileries, a street scene and one of La Maison Grise, including the lawn and the nymphs in the pond. I was slightly startled when, turning over the canvasses, he revealed a picture of Moulin Carrefour.

“That’s the mill,” I said.

“It’s an old one … painted some years ago. You recognized it.”

“Marie-Christine took me there.”

He turned it against the wall and showed me another picture, of a woman at a stall in the market. She was selling cheese.

“Do you sit in the street and paint?” I asked.

“No. I make sketches and come back and work on them. It is not really satisfactory, but necessary of course.”

“You specialize in portraits?”

“Yes. The human face interests me. There is so much there … if one can find it. So many people try to conceal that which would be most interesting.”

“So when you paint a portrait, you are trying to discover what is hidden?”

“One should know something about the subject if one is going to do a really good portrait.”

“And all the people you have painted are subjected to this … scrutiny.”

“It makes you sound like a detective,” said Robert. “You must have lots of information about people you paint.”

“Not really,” said Gerard, laughing. “What I discover is for me alone … and it is only with me when I am working on the picture. I want to do something which is true.”

“Don’t you find that people don’t really want to look so much what they are but what they would like to be?” I asked.

“The fashionable painter is usually the one who does just that. I am not a fashionable painter.”

“But if a flattering picture gives pleasure, what harm is there?”

“No harm at all. It is just not what I want to do.”

“I should like to be flattered,” said Marie-Christine.

“I daresay most people would,” added Angele.

“Do you think you really discover what secrets people are trying to hide?” I asked.

“Perhaps now and then. But the portrait painter often has a vivid imagination, and what he does not discover, he will imagine.”

“And does not always come up with the right answer.”

“What he likes to do is come up with some answer.”

“If it is the wrong one, his endeavours might seem to have been wasted.”

“Oh, but he has greatly enjoyed the experience.”

“It seems to me,” said Robert, “that one should be wary of having one’s portrait painted, if in the process one must submit to an analysis of one’s character.”

“I can see I have given a false impression,” said Gerard lightly. “I am really talking of an exercise practised for the artist’s pleasure. It is completely harmless.”

A shadow fell across the glass door which opened onto a roof, and I saw a figure there. A very tall man was looking into the room.

“Hello,” he said, in deeply accented French.

“Come in,” said Gerard unnecessarily, for the visitor was already stepping into the room.

“Oh … I’m intruding,” he said, surveying us. He smiled on us all. He was very blond, and in his late twenties, I imagined. His eyes were startlingly blue, and there was something overpowering about him—not only because of his size. His forceful personality was immediately apparent.

“This is Lars Petersen, my neighbour,” said Gerard.

I had heard the name before. He was the man who had painted Marianne.

Gerard introduced me. The newcomer obviously knew the others.

“It is delightful to see you all,” said Lars Petersen. “You must forgive my calling in such a manner. I came to borrow some milk. Have you any, Gerard? If I had known you were entertaining, I would have drunk my coffee without milk.”

“We have some coffee here,” said Angele. “It might be a little cold …”

“I’d like it however it comes.”

“We have milk here, too.”

“How kind you are to me.”

“Do sit down,” said Angele, and he took his place on the couch beside Marie-Christine.

“You’re a painter, too, are you not?” she said.

“I try to be.”

“And you live in the next studio … and you have come across the roof.”

“Well, it is not so hazardous as you might think. We can walk about on that roof, and there is actually a path from studio to studio. My studio is exactly like this one. They are a pair.”

Angele gave him the coffee, for which he thanked her profusely.

I thought Gerard looked mildly annoyed and was wishing his neighbour had not joined the party. The big man certainly had an effect. He was soon dominating the conversation … talking a great deal about himself: how he had been a student in Oslo and had suddenly had the idea that he must be a painter.

“It was like St. Paul on the road to Damascus,” he told us. He had suddenly seen the light. So he packed his bags and came to Paris … the Mecca of artists. Such friendly people. So like himself. “There we are, in our garrets … poor but happy. All artists should be happy.” He was looking rather mischievously at Gerard, who would, of course, not be exactly poor, coming from such a family. And was he happy? I did not think he was, which might have something to do with the death of his young wife.

“To starve in a garret is an essential part of the flowering of great art, so they say,” went on Lars Petersen. “So we are all living from day to day, knowing that we are on the road to fame and fortune, and the hardships of the present are the price to pay for the glories of the future. One day the name of Lars Petersen … and Gerard du Carron … will stand with that of Leonardo da Vinci. Never doubt it. That’s what we believe, anyway. And it is a nice comfortable belief.”

He told us how he had come to Paris. He had struggled for a few years … going from lodging to lodging. And then he had sold a few pictures. One of those pictures was a success. People talked of it.

I was perceptive on that day. I was immediately aware of the expression on Gerard’s face. It was fleeting, but it was there. He was thinking of Lars Petersen’s portrait of Marianne which had attracted so much attention.

“If you have one success, people get interested,” went on Lars Petersen. “I began to sell pictures. It was a step up. That’s what everyone needs. Now I have a fine apartment … just like this one. It’s an exact replica. And where could you find anything more suitable to our needs?”

He talked on, and I had to admit he was amusing. Though his French was fluent, he would often search for a word, throwing up his head and clicking his fingers, as though summoning someone to supply it. Someone—Marie-Christine, for instance—usually did. She was greatly amused by him, and I could see that she was enjoying the visit more since Lars Petersen had appeared.

He described his own country, the magnificence of the fjords. “Fine scenery. Paintable, but”—he lifted his shoulders and shook his head—”people would rather have the Louvre or Notre Dame … than all the wild scenery of Norway. Yes, yes, if you want to succeed, you must serve your apprenticeship in Paris. Paris is the magic word. You cannot be great without Paris.”

“So Gerard assures us,” said Robert. He glanced at Angele. “I think, my dear, that it is time we left.”

“It has been such fun,” cried Marie-Christine.

“You are not far away in the country,” said Lars Petersen. “Just a few miles from Paris, is it not?”

“Yes,” replied Gerard, “you should come to Paris more often.”

“We will,” cried Marie-Christine.

“It has been good to see you, Gerard,” said Angele. “Do come home soon.”

“I will.”

Gerard had taken my hand.

“I have so much enjoyed meeting you. I am glad you are in France. I should like to do a portrait of you.”

I laughed. “After all your warnings?”

“There are some people one sees and wants to paint. I feel that about you.”

“Well, I’m flattered, but I should be a little wary, shouldn’t I?”

“I promise you, the process would be painless.”

“We are going back the day after tomorrow.”

“As we were saying, you are not far away. Would you agree? It would give me great pleasure.”

“May I think about it?”

“Please do.”

“Would you come to La Maison Grise?”

“I would rather do it here. The light is so good. And I have everything I need here.”

“It would mean my staying in Paris.”

“For a week or so. Why not? You are here now. You could stay at the house. It is only a short way from there to the studio.”

I felt quite excited. It had certainly been a stimulating afternoon.

Later that day Angele came to my room.

She said: “I wanted to hear what you thought about the visit to Gerard.”

“I enjoyed it. It was very interesting.”

“He worries me, really. I wish he would come home.”

“But you know how he feels about his painting.”

“He could do it at home.”

“It wouldn’t be the same. Here he is with those people. Imagine the cafe society … the talks … the aspirations and the rivalries … all his friends who understand what he is talking about. Naturally he is happier here.”

“It was different when his wife was alive. She could look after him.”

“He seems to manage very well with Madame Garnier.”

Angele made a contemptuous gesture.

“And there is that man living close.”

“He is certainly a character.”

“I suppose you know him quite well.”

“He has been a neighbour of Gerard’s for some time. He’s always been very garrulous when I have seen him … talking about himself most of the time.”

“Gerard has asked to paint me.”

“I know. I heard him. That would be nice.”

“Do you think so?”

“I am sure it would.”

“I said that, after all these revelations, I was put on my guard.”

“Oh, that was just idle talk. Besides, you have no dark secrets.”

“Still …”

“I think he could do a good portrait of you. Some of his are really quite beautiful.”

“He did a great many of his wife, I suppose.”

“Oh yes. She was his chief model. There are some lovely ones. It was a pity there was all that fuss about the one Lars Petersen did. I think some of Gerard’s were as good. It’s just a matter of what takes the critic’s fancy.”

“He did not show us any that he had painted of her.”

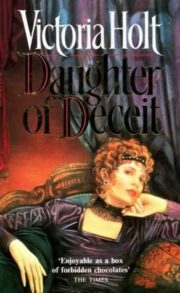

"Daughter of Deceit" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Daughter of Deceit". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Daughter of Deceit" друзьям в соцсетях.