“Yet he has realized he has a life to lead. He is now married.”

“I think he did it because he was sorry for Lisa. It was pity.”

“No matter what, he has married. Think about what I have said. You might come to realize that it is best … for both of us. Think about it, will you?”

“Yes, Gerard,” I said. “I will.”

I did think about it. It was never out of my mind. I was very fond of Gerard. I was drawn to the life of the studio. It had given me great pleasure to prepare meals for him; and now I was overwhelmed by a desire to comfort and care for him. I wanted to banish from his mind forever that notion that he had been responsible for Marianne’s death.

In a way I loved him. Perhaps if I had never known Roderick, that would have been enough. But Roderick was there. The memory of him would never go away. I knew that for the rest of my life I would dream of him.

And yet I was fond of Gerard.

And so my thoughts went on.

I would go to the studio as usual. There was always a great deal of coming and going, with the usual talk; but something else was cropping up. It had gradually seeped into the atmosphere for some time now. I sensed a general uneasiness; there were differences in opinions, and the young men were fierce in their arguments.

“Where is the Emperor leading us?” demanded Roger Lamont one day. “He thinks he is his uncle. He will end up at St. Helena if he is not careful.”

Roger Lamont was an ardent anti-royalist. He was young, dogmatic and fiery in his views.

“You’d have another revolution on our hands if you had your way,” said Gerard.

“I’d rid France of this Bonaparte,” retorted Roger.

“And set up another Danton … another Robespierre?”

“I’d have the people in command.”

“We did once before, remember? And look how that turned out.”

“The Emperor is a sick man with grandiose ideas.”

“Oh, it will work out all right,” said Lars Petersen. “You French get too excited. Let them get on with their business and we’ll get on with ours.”

“Alas,” Gerard reminded him. “We are involved, and their business is ours. We live in this country and its fortunes are ours. We’re in trouble financially. The press is not free. And I think the Emperor should restrain himself in his quarrels with the Prussians.”

They would go on arguing for hours. Lars Petersen was clearly not particularly interested. He interrupted them to talk about a certain Madame de Vermont, who had given him a commission to paint her portrait.

“She is in court circles. I’ll wager that before long I’ll have the Empress sitting for me.”

Roger Lamont jeered, and Lars turned to me. “Madame de Vermont saw your portrait and asked the name of the artist. She immediately engaged me to paint her. So you see, my dear Noelle, that it is to you I owe my success.”

I said how delighted I was to have been some use to him. And I was thinking how pleasant it was, sitting here and listening to their talk. I felt I was one of them.

It was a pleasant way of life. Was it possible that I could truly be part of it for the rest of mine? At times I believed I could, and then the memories would come back. I would dream of Roderick, and in those dreams he was urging me not to marry anyone else: and when I awoke the dreams seemed so real.

But he had married Lisa Fennell. That was the final gesture. He had accepted our fate as irrevocable. Surely I must do the same?

It was impossible. I could not do it, I told myself. Then I would shop in the markets, buy some delicacy, take it to the studio and cook it. And I would say to myself: This might be the way for me. But later … there would come the doubts.

Dear Gerard! I wanted so much to make him happy. I thought a great deal about Marianne. I could not believe that she was the kind of girl who would ride recklessly because she was so upset. I thought she was too superficial to have cared very deeply.

I wished that I could put an end to his terrible feelings of guilt. Perhaps I could discover something from Nounou.

I was obsessed by Marianne, and when our stay in Paris came to an end, I was almost eager to return to La Maison Grise, because I had a belief that from Nounou I might glean some useful information.

When Gerard said goodbye, he asked me to come back soon, and I promised I would.

“I know it is not what you hoped for,” he said. “But sometimes in life one has to compromise … and the result can be good. Noelle, I shall understand. I shall not reproach you for remembering him. I am prepared to take what you can give. The past hangs over me as it does over you. We can neither of us expect to escape entirely. But we should be good for each other. Let us take what life has to offer.”

“I think you may be right, Gerard, but as yet I am not sure.”

“When you are, come to me … come at once. Do not delay.”

I promised I would.

When I returned to La Maison Grise, I lost no time in calling on Nounou.

She was very pleased to see me.

“I’ve missed your visits,” she said. “I can see that Paris fascinated you as it did Marianne. It is that sort of city, is it not?”

I agreed that it was.

I was not sure how I could get round to asking her what I wanted to know. When I was in Paris, I had felt it would not be difficult.

We talked about Marianne, as we always did. She found more pictures. She talked of her hosts of admirers. “She could have married the highest in the land.”

“Perhaps she realized that after she had married Monsieur Gerard, and regretted the marriage.”

“Oh, that family has always been highly thought of. She did very well for herself. There’s none that could deny that.”

“Apart from the prestige the marriage brought, was she happy in it?”

“She was happy enough. She was greedy, my girl. As a child she would stretch out her little hands and say ‘Want it’ whenever she saw something that took her fancy. I used to laugh at her. ‘Mademoiselle Want It,’ that’s what I called her. I’m just going to put some flowers on her grave. Would you like to walk over to the cemetery with me?”

I was wondering what I could say to Nounou. I kept forming phrases in my mind. “If she had quarrelled with her husband, and he had told her to go, how would she have felt about that?” She would ask me how I could possibly have got such an idea into my head. I must not betray what Gerard had told me.

I watched her tend the grave. She knelt and prayed for a few moments. And as I stared at the gravestone, with her name and the date of her death, I could picture her beautiful face mocking me.

I am dead. I am buried. I shall haunt him for the rest of his life.

No, I thought, you shall not. I will find some way of freeing him from you.

Which sounded as though I had made up my mind to marry him. But later on I felt I could never marry anyone now. Roderick had gone out of my life, taking all my hopes of a happy marriage with him.

Robert had gone to Paris. He said, before he left, that the situation was getting somewhat grim. The Emperor was losing patience with Bismarck. He saw in him the enemy of all his plans for the greatness of France.

“It is a good thing,” Robert had said, “that Prussia is only a small state. Bismarck won’t want trouble with France, though he is as arrogant and ambitious for Prussia as the Emperor is for France.”

He thought he would be in Paris for some little time.

“When you feel like coming to the house, you’ll be welcome. Gerard will be delighted, too.”

I would go, I promised myself. But first I wanted more talks with Nounou.

Before I could do so, there was devastating news. It was a hot July day. Marie-Christine and I were in the garden when Robert unexpectedly returned from Paris. He was very excited.

We saw him go into the house and hurried after him. Angele was in the hall.

Robert announced: “France has declared war on Prussia!”

We were all astounded. I had heard the discussions in the studio, but had not taken them very seriously. This, of course, was what they had feared.

“What will it mean?” asked Angele.

“One good thing is that it can’t last long,” said Robert. “A little state like Prussia against the might of France. The Emperor would never have gone into this if he had not been certain of a quick victory.”

Over dinner, Robert said he would have to go back to Paris almost immediately. There would be precautions he would have to take, just in case the war was not over in a few weeks. He supposed he would be kept in Paris for a while.

“You should stay here in the country until we see what is going to happen,” he went on. “Paris is in a turmoil. The Emperor, as you know, has for some time been losing the sympathy of the people.”

The next day Robert went back to Paris. Angele accompanied him. She wanted to make sure that Gerard was looking after himself.

I was wondering what was happening at the studio. We were avid for news.

Several weeks passed. It was early August when we heard that the Prussians had been driven out of Saarbrucken, and there was great rejoicing. Everyone was saying that this would be a lesson to the Germans. However, within a few days the news was less good. It was only a small detachment which had been driven out of Saarbrucken, and the French had failed to take advantage of their small success. They were, therefore, routed and had retreated in confusion into the Vosges Mountains.

There were grim faces everywhere; there was murmuring against the Emperor. He had plunged France into war on the flimsiest pretext, because he wanted to show the world that he was another such as his uncle. But the French people did not want conquest and vainglorious military success. They wanted peace. And this was certainly not success. It was humiliating failure.

Through those hot August days we waited for news of the war. Not much seeped through to us, and I guessed that was a bad sign.

Robert came back for a brief visit. He advised us to stay in the country, though he must go back. Things were getting very difficult in Paris. The people were very restive. Students were gathering in the streets. The cafes and restaurants were crowded with people who wanted to arouse others to action.

The days of revolution were not far enough in the past to be readily forgotten.

I was seeing Nounou now and then. She had little interest in the progress of the war. I had not up to that time found an opportunity to bring up the matter which was very much in my mind. I wondered a great deal about Gerard. He was serious-minded and would, I knew, be deeply perturbed by the war.

Opportunity came suddenly. I was with Nounou one day and she was talking about Marianne. She had found a picture of her which she had forgotten existed. She had not seen it for years.

“It was at the back of one of the albums, tucked away under another picture. She must have hidden it. She never liked that one.”

“May I see it?” I asked.

“Come up,” said Nounou.

She took me to that room which I thought of as Marianne’s room. There were pictures of her on the wall, and on the table were those albums which were for Nounou a record of her darling’s life.

She showed me the picture.

“She looks a little bit saucy here, does she not? Up to tricks. Well, that was like her—but it shows more on that one.”

“And she wanted it to be hidden?”

“She said it was too revealing. It would put people on their guard.”

I studied it. Yes, I thought, there was something about it … something almost evil.

“I’m glad I’ve got her pictures,” said Nounou. “In my young days, there wouldn’t have been all these pictures. That Monsieur Daguerre brought them in. I don’t know what I’d do without my pictures.”

“If she didn’t like the picture, I wonder she did not destroy it.”

“Oh no … she’d never destroy any of her pictures. She’d look at them as often as I did.”

“It sounds as though she was in love with herself.”

“Well, why shouldn’t she be? Everyone else was in love with her.”

“She was happily married, wasn’t she?”

There was a slight pause. “Well, he was madly in love with her.”

“Was he?”

“Oh yes. Everybody was. He was jealous.” She laughed. “Well, you could understand that. Every man was after her.”

“Did she quarrel with her husband?”

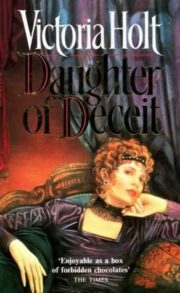

"Daughter of Deceit" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Daughter of Deceit". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Daughter of Deceit" друзьям в соцсетях.