“Your mother has a lovely face. There is a softness … a gentleness about her. She is beautiful, of course, but she has a sort of inner beauty. I believe that when people have faces like that they are really good.”

“What a nice thing to say. I want to tell her that. She will be amused. She doesn’t think she’s good at all. She thinks she’s a sinner. But you’re right. She is good. I often think how lucky I am to be her daughter.”

He pressed my arm and we were silent for a moment, then he said: “What happened to Roxana?”

“We did discover that there was a child named Aubrey de Vere, and he called himself the Earl of Oxford. He was the son of an actress and it was said that the earl had gone through a form of mock marriage with his mother.”

“That must have been the one, unless he made a habit of going through mock marriages.”

“I could imagine he might. That’s the maddening thing about these stories. One often doesn’t know how it turned out in the end.”

“One has to imagine it. I hope Roxana became a great actress and nemesis overtook the Earl of Oxford.”

“Matty discovered that he was notoriously immoral, but he was witty and popular at court, so I suppose he didn’t suffer for his misdeeds.”

“What a shame! Look. Here is a tea shop. Would you like to sit down for a while and then we can go to the theatre in time for the end of the play?”

“I should enjoy that.”

The tea shop was small and cosy; we found a place for two in a corner.

As I poured the tea, he talked about the holiday he planned in Egypt.

“An archaeologist’s dream,” he said. “The Valley of the Kings! The pyramids! So many relics of the ancient world. Imagine it all.”

“That is just what I am doing. It must be one of the most thrilling experiences possible to get into one of those tombs of the kings … though frightening in a way.”

“Exactly. I think the robbers of tombs had a lot of courage. When you think of all the myths and legends, you realize how amazing it is what people will do for gain.”

“How exciting it will be for you!”

“You’d enjoy it, I know.”

“I am sure I should.”

He looked at me intently and then stirred his tea slowly, as though deep in thought.

Then he said: “My father and your mother have been really great friends for years, haven’t they?”

“Oh yes. My mother has often said that she relies on him more than anyone else. Robert Bouchere is another of her friends of long standing. He is a banker in Paris and is often in London. I think your father comes first with her.”

He nodded thoughtfully.

“Tell me about your home,” I said.

“It’s called Leverson Manor. Leverson was an ancestor but the name got lost somewhere when one of the daughters inherited and married a Claverham.”

“And your mother?”

“She, of course, is a Claverham only by marriage. Her family have estates in the North. They are a very old family and trace their origins back right through the centuries. They rank themselves with the Nevilles and the Percys who guarded the North against the Scots. They have portraits of warriors who fought in the Wars of the Roses and farther back than that when they were fighting the Picts and the Scots. My father, as you know, is a gentle and kind man. He is very popular on the estate. They are all in awe of my mother and she likes to keep it that way. She gives the impression of being conscious that she married beneath her, which I suppose, strictly socially speaking, she did. Actually, she cares deeply about my father and me, her only son.”

“I can picture her so well. A rather terrifying lady.”

“She wants the best for us. The point is that we don’t always agree as to the best and that is when the conflict begins. If only she could rid herself of the belief that her blood is slightly more blue than my father’s, if only she could understand that some of us must do what we want and not what she decides is best for us … she would be a wonderful person.”

“I can see you are fond of her and of course you would have a portion of the bluer blood to mingle with the baser sort.”

“Well, I understand her. She is really a grand person and the fact is that she really is very often right.”

I believed I was getting a good picture of Lady Constance and life at Leverson Manor.

How I should love to see it! Not that I ever should. Of one thing I was certain: Lady Constance would never approve of her husband’s friendship with an actress, even a famous one. It was therefore wrong to expect this encounter to be other than one between casual acquaintances.

We could not linger indefinitely over the tea table, although he gave me the impression that he would have liked to.

I looked at my watch and said: “The play will be approaching the end.”

We came into the street and walked the short distance to the theatre. Before we parted at the door, he took my hand and looked at me earnestly.

“We must do this again,” he said. “I’ve enjoyed it thoroughly. I have so much to learn of the history attached to the theatrical world.”

“And I should like to hear more of the Roman remains.”

“We must arrange it. Shall we?”

“Yes.”

“When is the next matinee?”

“On Saturday.”

“Then shall it be then?”

“I should like that.”

I was lighthearted as I went up to the dressing room. Martha was there.

“Not such a good house,” she said. “I was never fond of matinees. They never seem the same as night. And we weren’t fully booked. She won’t like that. If there’s anything she hates, it’s playing to half-empty houses.”

“Was it half empty?”

“No … just not full. She’ll notice it. Trained eye and all that. She’s more audience-conscious than most.”

Contrary to Martha’s expectations, my mother was in a good mood.

“Jeffry slipped when he put his arm round me in ‘I’d love you if you were a shopgirl still.’ He grabbed me and pulled a button off my dress at the back, Martha.”

“He’s a clumsy beggar, that Jeffry,” said Martha. “I reckon he looked right down silly.”

“Not him. They love him … all that golden hair and the jaunty moustache. Half the audience are in love with him. What’s a little slip? It only makes him human. They come to see him as much as me.”

“Nonsense. You’re the bright light of the show and don’t you forget it. I haven’t worked my fingers to the bone to get you taking second place to Jeffry Collins.”

“Jeffry thinks he’s the one who pulls them in.”

“Well, let him. No one else does. Let’s have a look at that button. Oh, that’ll soon be put right for tonight.”

“Oh, tonight … it starts all over again tonight. I hate matinees.”

“Well, Noelle’s here to go home with us.”

“That’s nice, darling. Had a good afternoon?”

“Oh yes … very good.”

“Lovely to have you here.”

“And,” said Martha, “we’d better get a move on. Don’t forget there’s a show tonight.”

“Don’t remind me,” sighed my mother.

There were one or two people at the stage door, waiting for a glimpse of Desiree. She was all smiles and exchanged a few words with her admirers.

Thomas helped her into the carriage and Martha and I climbed in beside her. She waved gaily to the little crowd and, when we had left them behind, leaned back with half-closed eyes.

“Did you buy anything nice?” she asked me.

“No … nothing at all.”

I was about to tell her of the meeting with Roderick Claverham when I restrained myself. I was not quite sure how she had felt about my bringing him to the house. She had laughed it off, but I fancied she had found the situation embarrassing.

She had lived her life free of conventions and she had given so much to others. She had chosen to live as she pleased, and I had heard her say that if you don’t hurt anyone, what harm can you do?

As long as Lady Constance did not know of the rather special friendship between her husband and the famous actress, did it matter? To moralists, yes, it did; but Desiree was never one of those. “Live and let live,” she used to say. “That’s my motto.” But when Charlie’s secret life and his conventional one touched, perhaps that was time to pause and consider.

I was unsure, so I said nothing of the meeting with Roderick.

I led her to talk of the afternoon’s performance, which she was always ready to do; and finally we turned into the road and the horse pricked up his ears as, to our amusement, he always did, and would have broken into a gallop at this juncture if Thomas had not restrained him.

My mother said: “The darling knows he’s home. Isn’t that sweet?”

We were about to draw up when it happened. The girl must have run right in front of the horse. I wasn’t sure what happened exactly. I think Thomas swerved to avoid her and then she was lying stretched out on the road.

Thomas had pulled up sharply and jumped out. With my mother and Martha, I followed.

“Good heavens,” cried my mother. “She’s hurt.”

“She dashed right under Ranger’s feet,” said Thomas.

He picked her up.

“Is she very badly hurt?” asked my mother anxiously.

“Don’t know, madam. But I don’t think so.”

“Better bring her in,” said my mother. “Then we’ll get the doctor.”

Thomas carried the young woman into the house and laid her on the bed in one of the two spare bedrooms.

Mrs. Crimp and Carrie came running up.

“What is it?” gasped Mrs. Crimp. “An accident? My goodness, gracious me! What it the world coming to?”

“Mrs. Crimp, we need a doctor,” said my mother. “Thomas, you’d better go. Take the carriage and you can bring Dr. Green back with you. Poor girl. She looks so pale.”

“You could knock her down with a feather by the looks of her, let alone a horse and carriage,” commented Mrs. Crimp.

“Poor girl,” said my mother again.

She put her hand on the girl’s forehead and stroked her hair back from her face.

“So young,” she added.

“I think a hot drink would do her good,” I suggested. “With plenty of sugar in it.”

The girl opened her eyes and looked at Desiree. I saw that expression which I had seen so many times before, and I felt proud that even at such a time she could be aware of my mother.

Then I recognized her. She was the girl I had seen standing outside the house when we had come home from the theatre after the first night.

So … she had come to see Desiree. She was another of those stagestruck girls very likely—one of those who adored the famous actress and dreamed of being like her.

I said to Desiree: “I think she is one of your admirers. I’ve seen her before … outside the house … waiting for a glimpse of you.”

Even at such a time she could be pleased at public appreciation.

The hot tea was brought and my mother held the cup while the girl drank.

“There,” she said. “That’s better. The doctor will soon be here. He’ll see if there is any harm done.”

The girl half raised herself and my mother said soothingly: “Lie down. You’re going to rest here until it is all right for you to go. You’ll be very shaken, you know.”

“I … I’m all right,” said the girl.

“No, you are not … at least not for going off. You are going to stay here until we say you may go. Is there anyone you would like a message sent to … someone who will be anxious about you?”

She shook her head and in a blank voice which betrayed a good deal said: “No … there is no one.”

Her lips quivered and I saw the deep sympathy in my mother’s eyes.

“What is your name?” asked my mother.

“It’s Lisa Fennell.”

“Well, Lisa Fennell, you are going to stay here for the night at least,” replied my mother. “But first we have to wait for the doctor.”

“I don’t think she has been hurt much,” said Martha. “It’s shock. That’s what it is. And you have a show tonight. You know how rushed these matinee days always are. Matinees ought to be abolished, if you ask my opinion.”

“Nobody is asking your opinion, Martha, and you know how necessary it is to squeeze every penny out of the public if we are to carry on.”

“I reckon we could do without matinees,” persisted Martha.

“Think of all the people who can only get away one half day a week.”

“I’m thinking of us, ducks.”

“Our duty in life is to think of others … particularly in the theatre.”

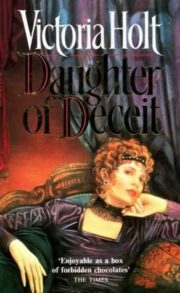

"Daughter of Deceit" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Daughter of Deceit". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Daughter of Deceit" друзьям в соцсетях.