Georgiana is now at school, where she is happily established. She was sorry not to see you and is looking forward to your next meeting. She will be much grown by the time you return. She has lost the sad, pinched look she had when Papa passed away, largely thanks to your mother. I am exceedingly grateful for it. I thought at one time that she would never recover, but all things pass and she is happy again.

I am not surprised by what you tell me of George Wickham. I have seen him several times in London myself. On the first occasion he tried to speak to me, but as he was under the impression there were three of me, he did not know which one to address and so he contented himself with falling over instead. On the last occasion, he was too busy with his women to notice me. Unless he changes, I doubt if he will even want the living. He has not shown any interest in the church, and I do not think he has any intention of becoming ordained.

You will be welcome at Pemberley when you return. Send a letter to announce your arrival if there is time or, if not, come anyway.

Your cousin,

Darcy

NOVEMBER

Mr Wickham to Mr Darcy

The Red Lion Inn, London,

November 6

My dear Darcy,

I owe you a letter! It must be nearly six months since I received your last. I neglected to thank you for the one thousand pounds, for which I must apologise. I would have done so when I saw you in London, but you did not see me and I could not get away from my friends, so I am repairing the omission now. I must thank you, too, for paying for my father’s funeral expenses and settling the small debts I had at the time. I hear you have appointed a new estate manager. I only hope he may be half the man my father was, God rest his soul.

I have been giving some thought to my future and I have decided not to go into the church, and so I have decided to relinquish all claim to the living your father so generously promised me. I hope you will now be able to bestow it elsewhere.

You will not think it unreasonable of me to ask for some kind of pecuniary advantage instead of the living. I mean to go into the law, and as you are aware, the interest on one thousand pounds—the sum your father generously left me—does not go very far. Your honoured father, I am sure, would have wanted me to have something in lieu of the living, and a further sum of money would be useful to me. Three thousand pounds should pay for my studies.

Your very great friend,

George

Mr Darcy to Mr Wickham

Pemberley, Derbyshire,

November 8

I am very pleased you have decided not to go into the church. I am also pleased you have decided to study for the law. I will send you three thousand pounds as soon as you resign all claims to the living.

Yours,

Darcy

Mr Wickham to Mr Darcy

The Red Lion Inn, London,

November 17

Thank you for the three thousand pounds in return for my forfeit of the living. You may be certain I will put it to good use. I will make your revered father proud of me.

Your very great friend,

George

1798

MAY

Miss Elizabeth Bennet to Mrs Gardiner

Longbourn, Hertfordshire,

May 6

Dear Aunt,

I am writing to thank you for the bonnet you sent me for my birthday, which I think is adorable and which is the envy of my friends. I have already worn it, you will be pleased to know. It adorned my head this morning on a walk into Meryton, where it was much admired. How lucky I am to have an aunt who lives in the capital and who can send me the latest styles! Thank you again for such a welcome gift.

I am being very much spoilt and I am having an enjoyable day. Jane has given me a new fan, which she painted herself, and Mary copied an extract from Fordyce’s Sermons in her best handwriting and then framed it. She presented it to me ‘with the hope that it would guide me through the Torrents and Turmoils of a Woman’s Life’; Kitty gave me a handkerchief, and Lydia said that she would have given me a new pair of dancing slippers, but she had already spent her allowance. I had a new pair of boots from Papa, for my others were worn through. Mama gave me a new gown, in the hope it would help me to catch a husband, and said, sighing, ‘Eighteen years old and still unwed! It is a sad day, Lizzy, a very sad day indeed.’

We are going to my aunt Philips’s this evening for a celebratory game of lottery tickets. Charlotte Lucas will be there and Susan Sotherton, so I will have some congenial company. There is a rumour abroad that Charlotte’s father means to give up his business and move out of Meryton now that he has been given a knighthood. I hope to hear more about it from Charlotte tonight.

Susan is not so fortunate in her papa. He is still drinking a great deal more than is good for him, and his gambling is causing the family some unease. They have already had to sell two of the carriage horses and more economies look certain to follow—if Mr Sotherton can be persuaded to make them.

It is fortunate that Netherfield Park is entailed on Frederick, so that at least Mr Sotherton cannot gamble the roof from over their heads, as he does not own it but only holds it in trust for his son.

An entail is a strange thing, is it not? Here are we, bemoaning the fact that our estate is entailed, so that Papa cannot leave it to Mama (or anyone else he pleases) when he dies, but must leave it to Mr Collins, meaning that we will no longer have a home.

But with Susan’s family it is quite the reverse. They are relieved that Netherfield Park is entailed, for otherwise their papa could sell it and then they would no longer have anywhere to live. Mama hopes that one of us will marry Frederick, but as he appears to be quite as fond of drinking and gambling as his papa, we are none of us inclined to have him. We will not marry until we find men we like, admire, love and respect. Or, at least, Jane and I will not, though I cannot answer for my younger sisters, who seem to think that marriage to anyone is an object, just so long as they can do it by the age of sixteen.

Thank you again for my bonnet. It will have a second outing this evening, where I hope to astonish everyone with my finery.

Your loving niece,

Lizzy

Mrs Bennet to Mrs Gardiner

Longbourn, Hertfordshire, May 6

Ah! Sister, it is a sad day, a sad day indeed. To think I now have two daughters of eighteen years old or more and neither of them is married, nor in a way to being so. It is hard on a mother, very hard indeed. You know nothing of it yet, your children are still too young to be a worry to you, but it is a sore trial, it is a very sore trial indeed. And it plays havoc with my nerves. I have such palpitations when I think about it, such beatings of my heart, but no one here cares about it and no one pities me.

I did think, when Jane visited you a few years ago, and she met that nice young man in London who wrote her some poems, that she would soon be married, but it all came to nothing. You must ask her to visit you again. She can come to London at any time and Lizzy, too, can come at a moment’s notice. There will be more young men for them in London than there are in Meryton.

Indeed, I do not know who there is for them to marry here. There is only Frederick Sotherton, a handsome young man to be sure, and the heir to Netherfield Park, but wild, sister, very wild.

If the Lucas boys were older…But then, the Lucases never had any compassion, and their sons are too young even for Lydia. Do you not know anyone in London? We could all pay you a visit. We have not seen you or my brother for ever such a long time. You have only to say the word and we will be there in a trice, even though it is not pleasant for me to go out and about at my time of life. But no sacrifice is too great for my girls.

Your poor sister,

Janet

Mrs Gardiner to Miss Elizabeth Bennet

Gracechurch Street, London,

May 7

My dear Lizzy,

I am very glad that the bonnet was to your liking. I hope your day was enjoyable and that your mama did not bemoan your single state for too long. I am relieved that neither you nor Jane is inclined to have Frederick Sotherton. I remember him from my last visit—a young man who will get worse before he gets better, I dare say. I am sorry for Susan and her sisters. Their situation is far worse than yours; for, if your mama could only see it, there is very little danger of your papa dying for thirty years or more, by which time it is reasonable to assume that one of you will be settled in life and can help the others if need be. And if not, you can always come and live with us here.

But in this particular I agree with her: there are very few suitable young men in Meryton and so I have written to your mama, inviting you all to stay for a few weeks.

Your father, I dare say, will not feel he can join you, but we hope that your mama and sisters will stay with us until the end of June. You have not seen the children since Christmas and if you do not come soon, you will hardly recognise them when next you see them. Try to persuade your father to make one of the party. It will do him good to leave his library for a short while.

Give my love to your sisters,

Your fond Aunt Gardiner

Mrs Bennet to Mrs Gardiner

Longbourn, Hertfordshire,

May 9

Sister! You are so good to us! A few weeks in London is just what I need to set me up, and Jane will find someone, I am sure of it. All that beauty cannot be for nothing! We will have her married before the end of the summer, I am certain!

Your sister,

Janet

Miss Elizabeth Bennet to Miss Charlotte Lucas

Gracechurch Street, London,

May 20

Dearest Charlotte,

How welcome it is to be in London and with my aunt once again. To be sure, Jane and I have to suffer Mama’s constant hints about finding husbands, but we have an ally in our aunt, who is full of sympathy and calm good sense. She, at least, does not want us to catch the attention of every man between the ages of twenty and sixty, and can talk about other things than fortunes, expectations and handsome faces. She even refrains from talking about bridal bouquets if we should happen to dance twice with the same young man. And yet, if anything were to persuade me to marry, it would be my aunt’s example, because between her and my uncle there is love and understanding, with a great deal of mutual admiration and respect. The house is a happy one and I must confess, if I could find the same, I would be willing to enter into the married state.

But for now I am enjoying being unencumbered and delighting in the sights of London. We have been to the Lyceum Theatre and been well entertained with The Hypocrite, a play taken from Molière’s Tartuffe; we have been shopping and have bought some very fine muslin and a serviceable sarsenet from Grafton House; we have visited the museum and the British Gallery; we have walked in the parks and eaten ices at Gunter’s; in short, we have been devoting ourselves to pleasure!

The little children are thriving and are all benefiting from Jane’s company. She plays with them constantly and is always patient with them, and it is not difficult, for they are all of them well behaved.

The only person not very happy is my uncle. The war is bad for trade and he wishes it to end as soon as possible. We have met a number of émigrés here in London and they have seen horrors in their native France. It makes me very glad for what we have: a country where we might live out our lives in safety.

Does your brother still dream of going into the army? I hope not, or your mama will not know one easy day, worrying whether or not he is safe. Persuade him he would be better off joining the church, or following your papa into trade.

We will be here for another six weeks at least and we rely on you for news of home. Papa has promised to write but his letters are few and far between.

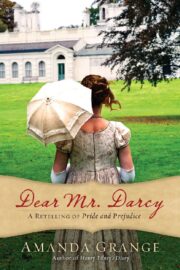

"Dear Mr. Darcy: A Retelling of Pride and Prejudice" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Dear Mr. Darcy: A Retelling of Pride and Prejudice". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Dear Mr. Darcy: A Retelling of Pride and Prejudice" друзьям в соцсетях.