“I do,” said his lordship, with the ghost of a laugh. “Go on, what next? I wish I had seen all this.”

“Do you, begad?” said his uncle. “You might have had my place for the asking. Well, I said you’d gone. Young Comyn took it up in that finicky voice of his. ‘I apprehend, sir,’ says he, that his lordship is by now upon the road to Newmarket.’ Avon turns his glass on him at that. ‘Indeed!’ says he, devilish polite. ‘I fear my son has untidy habits. This gentleman’ — and he points his quizzing-glass at Quarles — ‘this gentleman — I think unknown to me — is no doubt his latest victim?’ I can’t give you his tone, but you know how he says things like that, Vidal.”

“None better. Oh, but I make him my compliments. He comes off with the honours. Did he make my apologies?”

“Well, now you mention it, I believe he did,” said Rupert. “But he divided the honours with that Comyn lad. We’d all lost our tongues. But Comyn says — which I thought handsome of him — ‘As to that, sir, the late affair was in a sort forced upon his lordship. I believe, sir, no man could swallow what was said, though I am bound to confess that neither of the principals was sober.’ And I thought to myself, well, you must be damned sober, my lad, to get all that out without so much as a stammer.”

The Marquis’s face showed his interest. “Said that, did he? Mighty kind of him.” He shrugged, half smiling. “Or mighty clever.”

Léonie, who had been gazing into the fire, raised her head at that. “Why was it clever?”

“Madame, I spoke a thought aloud.” He looked at the clock again. “I can’t stay longer. Tell my father I will wait on him in the morning. To-night I have an engagement I can’t break.”

“Dominique, don’t you understand that if that man dies, you must not be in England?” Léonie cried. “Monseigneur says that this time there will be trouble. It has happened too often.”

“So I’m to make off like a scared mongrel, eh? I think not!” He bent over her hand for a moment. “Pray do not show that anxious face to the world, maman; it accords very ill with our dignity.”

In another moment he was gone. Léonie looked dolefully at Lord Rupert. “Do you suppose it is that bourgeoise, Rupert?”

“Devil a doubt!” said his lordship glumly. “But I’ll tell you what, Léonie; if we can pack him off to France there’ll be an end to that affair.”

It was as well for his peace of mind that he did not follow his nephew that evening. The Marquis stayed only to change his mud-stained garments, and was off again within twenty minutes, bound for the Theatre Royal. The play was more than half over, and in one of the boxes Sophia Challoner displayed a pouting countenance. Eliza Matcham had been twitting her the whole evening on the non-appearance of her fine beau, and she was in no very good humour. Her sister, with Cousin Joshua assiduously at her elbow, said tranquilly that the Marquis could hardly be expected to come after the happenings of the night before.

For the tale of the duel had spread like wildfire, so that the backwash of the sea of rumour had already reached Miss Challoner’s ears. It had also reached those of Cousin Joshua, who was not slow to say what he thought of the profligate Marquis. Sophia told him sharply that it was presumption in him to judge one so far above him, and by the time he had thought out a suitable retort, she had turned her white shoulder, and was talking with great vivacity to Mr. Matcham. Cousin Joshua addressed the rest of his homily to Miss Challoner, who listened in silence. Her gaze was so abstracted that he was beginning to suspect her of inattention. Then he observed a change in her expression. She stiffened, and her eyes grew intent and widened a little. Even Joshua could not suppose that this sudden interest was caused by his discourse, and he turned his head to see what had caught her eye.

“Upon my soul!” he said, puffing out his cheeks. “Shameless! If he has the effrontery to approach Sophia I shall know how to act.”

The Marquis of Vidal was standing in the pit, raking the boxes with his quizzing-glass.

A laugh trembled on Miss Challoner’s lips. Shameless? Of course he was shameless, but he was sublimely unconscious of it, unconscious too of the notice he was attracting from all who recognized him.

Mary looked at her cousin at last. “That is just as well, Joshua,” she said, “for I think he is going to approach her now.”

Mr. Simpkins saw the Marquis elbowing his way through the crowd in the pit, and tugged at Sophia’s sleeve. “Cousin!” said he, “I cannot but consider myself responsible for you, and I forbid you to speak with that profligate.”

This had not quite the desired effect. Sophia’s pout turned to an expression of sparkling eagerness. “Oh, is he here? Where? I do not see him. I knew he would never fail me. How I shall scold him for being so late!”

The Marquis had disappeared from the floor of the house by this time, and in a few minutes his knock fell on the door of the box, and he entered.

Sophia greeted him with a smile that reproached and yet beckoned. “Why, is it you indeed, my lord? I vow I had given you up. La, we have been hearing such tales of you! I declare I am half afraid of you.”

“Are you? Why?” inquired his lordship, kissing her hand. “Do you think I would hurt anything half so pretty as you?”

“Oh, lord, I don’t know what you might not do if I angered you,” laughed Sophia.

“Then don’t anger me,” advised the Marquis. “Walk with me in the corridor instead. The curtain won’t go up for a few minutes yet.”

“No, but do you know this is the fifth act? Positively, you have only come in time to hear the end of the play, and the farce.”

“Well, you had better instruct me in what it is all about,” said his lordship coolly.

“You don’t deserve that I should,” Sophia said, getting up from her chair. “Well, if I do walk with you outside, it will only be for a moment.”

Mr. Simpkins cleared his throat portentously, attracting the Marquis’s somewhat bored notice. “You spoke, sir?” Vidal said with so much haughtiness that Mr. Simpkins became flustered, and stammered something quite inaudible.

The Marquis smiled a little, and was just about to leave the box, with Sophia on his arm, when he caught sight of Miss Challoner’s flushed countenance. His brows lifted slightly. What the devil was the girl blushing for? She looked up as though she felt his gaze upon her, and her eyes met his steadily for a moment. He read disdain in them, and was amused, and asked Sophia as soon as they were out of the box what he had done to offend her sister.

She shrugged up her pretty shoulders. “Oh, sister doesn’t approve of your dreadful wicked ways, my lord.”

He suffered from a moment’s surprise. Nothing in Sophia, or her mamma and cousins had led him to suspect that her sister was likely to be strait-laced. Mrs. Challoner he wrote down as an elderly harpy; the Matchams were frankly vulgar. He laid his right hand on Sophia’s, lying on his arm. “Strait-laced, is she? Are you so, too?”

She raised her eyes to his, and saw them gleaming with some light that both frightened and excited her. Her colour fluctuated deliriously. The Marquis shot a quick look up and down the deserted corridor, and caught Sophia hard against his breast. “One kiss!” he said in a voice made suddenly husky with passion, and took it.

She made a half-hearted struggle to break free. “Oh, my lord!” she protested. “Oh, no, you must not!”

He had her fast round the waist, and with his free hand he cupped her chin, holding her head up so that he might look into her face. “You can’t keep me at arm’s length for ever, you little beauty. I want you. Will you come to me?”

The direct attack flustered her. She began to say: “I don’t know what you mean,” but he interrupted her: “Everything of the most dishonourable. Remember that, my pretty dear, for I don’t cheat, at love or cards.”

Her lips formed a soundless “oh” of astonishment. He kissed them, and partly from nervousness (for he had shaken her) and partly from coquetry, she giggled. He had no further doubts, but laughed back at her. She had an odd fancy, unusual in one so matter-of-fact, that little devils danced in his eyes. “I see we understand each other,” he said. “Listen to me now. I take it you’ve heard of last night’s affair? I may have to leave the country for a spell in consequence.”

She broke in with a little cry of dismay. “Leave the country? Oh, no, my lord!”

“I won’t leave you, my pretty, I promise. I’ve a mind to take you to Paris with me. Will you come?”

The colour flooded her cheeks. “Paris!” she gasped. “Oh, Vidal! Oh, my lord! Paris!” To her it spelled gaiety, fine dresses, trinkets, all that she craved of life.

He had no difficulty in reading her thoughts. “I’m rich; you shall have all the pretty things your own prettiness deserves. I’ll hire an hôtel for you; as its mistress you will play the hostess to my friends; in France these arrangements are understood. I know of a dozen such establishments. Do you choose to come with me, or not?”

Her native hardheadedness made her play for time, but her imagination was already running riot. The picture he drew lured her; she thought recklessly that she cared very little for the marriage-tie if she could live in Paris, where such arrangements, Vidal said, were understood. “How can I answer you, my lord? You — I protest you take me by surprise. I must have time!”

“There is no time. If Quarles dies, it’s farewell to England for me. Give me your answer now, or kiss me and say goodbye.”

She had only one steadfast thought, and that was that she would not let him slip through her fingers. “No, no, you cannot be so cruel!” she said with a tiny sob.

He was quite unmoved, but his hot gaze seemed to devour her. “I must. Come! Are you afraid of me that you hesitate?”

She drew away from him, a hand at her breast. “Yes, I am afraid,” she said breathlessly. “You force me — you are cruel ...”

“You need not be afraid: I adore you. Will you come?”

“If — if I say no?”

“Then let us kiss and part,” he said.

“No, no, I cannot leave you like that! I — oh, if you say I must, I will come with you!”

Rather to her surprise he showed neither rapture nor relief. He said only: “It will be soon. I will send you word to your lodgings.”

“Soon?” she faltered.

“To-morrow, Friday — I can’t say. You need bring nothing but the clothes you stand in.”

She gave an excited laugh. “An elopement! Oh, but how shall I contrive to slip off with you?”

“I’ll spirit you away safe enough,” he said, smiling.

“How? Where must I meet you?”

“I will let you know. But, remember, no word of this to a soul, and when you hear from me do exactly what I shall tell you.”

“I will,” she promised, larger and more mercenary issues for the moment forgotten.

When she returned to the box, alone, the curtain had already gone up on the fifth act. She was still flushed by excitement, and met her sister’s look with a defiant toss of her head. Let Mary frown if she would: Mary had no brilliant future before her; Mary might consider herself fortunate if she caught Cousin Joshua for a husband. Sophia gave herself to ecstatic imaginings.

The Marquis, meanwhile, betook himself to Timothy’s and created a sensation.

“Good God, it’s Vidal!” ejaculated Lord Cholmondley.

Mr. Fox, who was playing piquet with him, tranquilly dealt a fresh hand. “Why not?” he inquired.

“Cold-blooded devil!” marvelled Cholmondley.

Mr. Fox looked bored, and waved a languid hand at the Marquis.

Vidal was standing just inside the card-room, apparently surveying the company. There was just a moment when all play was suspended, and heads turned in his direction. The sudden silence was broken by an inebriated gentleman seated by the window, who called out: “Hey, Vidal, what time did you make? Laid a monkey you’d not do it under the four hours.”

“You have lost your stake, my lord,” said the Marquis. He perceived Mr. Fox, and began to make his leisurely way across the room to his table.

A hum of talk broke out. Many disapproving glances were cast at Vidal’s tall figure, but he seemed unaware of them and passed to Mr. Fox’s side, a picture of cool unconcern.

Cholmondley had laid down his cards. “Is that true?” he demanded. “You made it in the four hours?”

The Marquis smiled. “I made it in three hours and forty-four minutes, my dear.”

“Man, you were drunk!” Cholmondley cried. “I’d say it was impossible!”

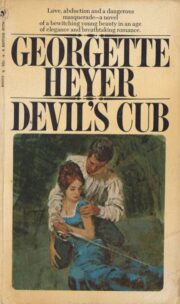

"Devil’s Cub" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Devil’s Cub". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Devil’s Cub" друзьям в соцсетях.