“Let us say, rather, au revoir,” Avon answered. “I will spare you my blessing, which I cannot conceive would benefit you in the least.”

Upon which they parted, each one understanding the other tolerably well.

Vidal’s interview with his mother lasted much longer, and was to him even more unpleasant. Léonie had no reproaches for him, but she was plainly unhappy, and the Marquis hated to see his mother unhappy.

“It’s my damnable temper, maman,” he said ruefully.

She nodded. “I know. That is why I am feeling very miserable. It is no good people saying you are a devil like all the Alastairs, because me, I know that it is my temper that you have, mon pauvre. You see, there is very black blood in my family.” She shook her head sadly. “M. de Saint-Vire — my father, you understand — was of a character the most abominable. And hot-headed! He shot himself in the end, which was a very good thing. He had red hair like mine.”

“I haven’t that excuse,” said her son, grinning.

“No, but you behave just as I should like to when I am enraged,” Léonie said candidly. “When I was young I was very fond of shooting people dead. Of course, I never did shoot anyone, but I wanted to — oh, often! I meant to shoot my father once — which shocked Rupert — it was when M. de Saint-Vire kidnapped me, and Rupert saved me — only Monseigneur arrived, and he would not at all permit it.” She paused, wrinkling her brow. “You see, Dominique, I am not a respectable person, and you are not a respectable person either. And I did want you to be.”

“I’m sorry, maman. But I don’t come of respectable stock, either side.”

“Ah, but the Alastairs are quite different,” Léonie said quickly. “No one minds if you have affaires. Of course, if you are a very great rake people say you are a devil, but it is quite in the mode and entirely respectable. Only when you do things that other people do not do, like you, and make scandals, then at once you are not respectable.”

He looked down at her half-smiling. “What am I to do, maman? If I made you a promise to become respectable I am very sure I should break it.”

She slipped her hand in his. “Well, I have been thinking, Dominique, that perhaps the best thing would be for you to be in love and marry somebody,” she said confidentially. “I do not like to say this, but it is true that before he married me, Monseigneur was a very great rake. A vrai dire, his reputation was what one does not talk about. When he made me his page, and then his ward, it was not to be kind, but because he wanted to be revenged upon M. de Saint-Vire. Only then he found that he would like to marry me, and do you know, ever since he has not been a rake at all, or done anything particularly dreadful that I can remember.”

“But I could never hope to find another woman like you, maman. If I could I promise you I’d marry her.”

“Then you would make a great mistake,” said Léonie wisely. “I am not at all the sort of wife for you.”

He did not pursue the subject. He was with her for an hour and more; it seemed as though she could not let him go. At last he wrenched himself away, knowing that for all her brave smiles she would weep her heart out once he was gone. He had given his word to her that he would leave London that night; he had much to do in the few hours left to him. His servants were sent flying on various errands, one to Newhaven to warn the captain of his yacht, the Albatross, that his lordship would sail for France next day, another to his bankers, a third to a quiet house in Bloomsbury with a billet, hastily scrawled.

This was delivered to an untidy abigail who received it in a hand hastily wiped upon her apron. She shut the door upon the messenger, and stood turning the heavily sealed letter over in her hand. Sealed with a crest it was; she wouldn’t be surprised if it came from the handsome lord that was running after Miss Sophy, only that it was directed to Miss Challoner.

Miss Challoner was coming down the stairs with her marketing-basket on her arm, and her chip hat tied over her curls. Miss Challoner, for all she was better educated than her sister, was not too grand to do the shopping. She had constituted herself housekeeper to the establishment soon after her return from the seminary, and even Mrs. Challoner admitted that she had the knack of making the money last longer than ever it had done before.

“What is it, Betty?” Mary asked, pulling on her gloves.

“It’s a letter, miss, brought by a footman. For you,” added Betty, in congratulatory tones. Betty did not think it was fair that Miss Sophy should have all the beaux, for Miss Mary was a much nicer-spoken lady, if only the gentlemen had the sense to see it.

“Oh?” said Mary, rather surprised. She took the letter. “Thank you.” Then she saw the direction, and recognized Vidal’s bold handwriting. “But this is — ” She stopped. It was addressed to Miss Challoner sure enough. “Ah yes! I remember,” she said calmly, and slipped it into her reticule.

She went on out of the house, and down the street. It was Vidal’s hand; not a doubt of that. Not a doubt either that it was intended for her sister. The scrawled direction indicated that the note had been written in haste; it would be very like the Marquis to forget the existence of an elder sister, thought Mary with a wry smile.

She was a little absent-minded over the marketing, and came back with slow steps to the house. She ought to give the billet to Sophia, of course. Even as she admitted that, she realized that she would not give it to her, had never meant to from the moment it had been put into her hand. There had been an air of suppressed excitement about Sophia all the morning; she was full of mystery and importance, and had twice hinted at wonders in store for her, but when questioned she had only laughed, and said that it was a secret. Mary was anxious as she had not been before; this letter — and after all it was certainly directed to herself — might throw a little light on Sophia’s secret.

It threw a great deal of light. Safe upstairs in her bedroom, Mary broke open the seal, and spread out the single thick sheet of paper.

“Love — ”the Marquis began — “It is for to-night. My coach will be at the bottom of your street at eleven. Join me there and bring nothing that you cannot hide beneath your cloak. Vidal.”

Miss Challoner’s hand crept to her cheek in a little frightened gesture she had had from a child. She sat staring at the brief note till the words seemed to start at her from the page. Just that curt command to decide Sophia’s future! Lord, but he must be sure of her! No word of love, though he called her by that sweet name; no word of coaxing; no entreaty to her not to fail him. Did he know then that she would go with him? Was this what they had arranged in that stolen interview last night?

Miss Challoner started up, crumpling the letter in her clenched hand. Something must be done and done quickly. She could burn the message, but if Sophia failed Vidal tonight, would there not be another to-morrow? She had no notion where Vidal meant to take her sister. A coach: that meant some distance. Doubtless he had a discreet house in the country. Or did he intend to cheat Sophia with a pretended flight to Gretna Green?

She sat down again, mechanically smoothing out the letter. It was of no use to show it to her mother; she knew from Sophia what absurd dreams Mrs. Challoner cherished, knew enough of that lady, too, to believe her capable of the crowning folly of winking at an elopement. Her uncle could do nothing, as far as she could see, and she had no wish to blazon Sophia’s loose behaviour abroad. When the idea first came to her she did not know; she thought it must have been hidden away in her brain for a long while, slowly maturing. Again her hand stole to her cheek. It was so daring it frightened her. I can’t! she thought. I can’t!

The idea persisted. What could he do after all? What had she to fear from him? He was hot-tempered, but she could not suppose that he would actually harm her, however violent his rage.

She would need to act a part, a loathsome part, but if she could do it it would end the Marquis’s passion for Sophia as nothing else could. She found that she was trembling. He will think me as light as Sophia! she reflected dismally, and at once scolded herself. It did not matter what he thought of her. And Sophia? What would she say? Into what transports of fury would she not fall? Well, that did not signify either. It would be better to bear Sophia’s hatred than to see her ruined.

She consulted the letter. Eleven o’clock was the hour appointed. She remembered that she was to spend the evening with her mother and sister at Henry Simpkins’ house, and began to lay her plans.

There was a table by the window with her writing-desk upon it. She drew up a chair to it, and began to write, slowly, with many pauses.

“Mamma — ” she began, as abruptly as the Marquis — “I have gone with Lord Vidal in Sophia’s place. His letter came to my hand instead of hers; you will see how desperate is the case, for it is plain he has no thought of marriage. I have a plan to show him she is not to be had so easily. Do not be afraid for my safety or my honour, even tho’ I may not reach home again till very late.”

She read this through, hesitated, and then signed her name. She dusted the sheet, folded it up with the Marquis’s note to Sophia, and sealed it, directing it to her mother.

Neither Mrs. Challoner nor Sophia made much demur at leaving her behind that evening. Mrs. Challoner thought, to be sure, that it was a pity she must needs have a sick headache on this very evening when Uncle Henry had promised the young people a dance, but she made no attempt to persuade her into accompanying them.

Miss Challoner lay in bed with the hartshorn in her hand, and watched Sophia dress for the party.

“Oh, what do you think, Mary?” Sophia chattered. “My uncle has contrived to get Dennis O’Halloran to come. I do think he is too dreadfully handsome, do you not?”

“Handsomer than Vidal?” said Mary, wondering how Sophia could prefer the florid good looks of Mr. O’Halloran to Vidal’s dark stern beauty.

“Oh well, I never did admire black hair, you know,” Sophia replied. “And Vidal is so careless. Only fancy, sister, nothing will induce him to wear a wig, and even when he does powder his hair the black shows through.”

Mary raised herself on her elbow. “Sophy, you don’t love him, do you?” she said anxiously.

Sophia shrugged and laughed. “La, sister, how stupid you are with all that talk of love. It is not at all necessary to love a husband, let me tell you. I like him very well. I do not mean to love anyone very much, for I am sure it is more comfortable if one doesn’t. Do you like my hair dressed a la Venus?”

Mary relaxed again, satisfied. When Sophia and her mother had left the house she lay for a while, thinking. Betty came in with her supper on a tray. Her appetite seemed to have deserted her, and she sent the tray away again almost untouched. At ten o’clock Betty went up the steep stairs to her little chamber, and Mary got out of bed, and began to dress. Her fingers shook slightly as she struggled with laces and hooks, and she felt rather cold. A search through one of Sophia’s drawers, redolent of cedar-chips, brought to light a loo-mask, once worn at a carnival. She put it on, and thought, peering at herself in the mirror, how oddly her eyes glittered through the slits.

She had some of the housekeeping money in her reticule; not very much but enough for her needs, she hoped. She hung the bag on her arm, put on a cloak, and pulled the hood carefully over her head.

On the way down the stairs she stopped at her mother’s room, and left the letter she had written on the dressing-table. Then she crept noiselessly down to the hall, and let herself out of the silent house.

The street was deserted, and a sharp wind whipped Mary’s cloak out behind her. She dragged it together, and holding it close with one hand, set off down the road. The night was cold, and overhead hurrying storm-clouds from time to time hid the moon.

Mary came round the bend in the street, and saw ahead of her the lights of a waiting chaise. She had an impulse to go back, but checked it, and walked resolutely on.

The light was very dim, but she was able as she drew closer to distinguish the outline of a travelling chaise drawn by four horses. She could see the postillions standing to the horses’ heads and another figure, taller than theirs, pacing up and down in the light thrown by the flambeaux burning before the corner house.

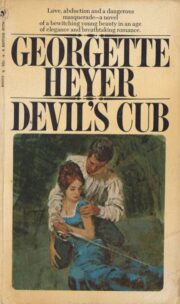

"Devil’s Cub" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Devil’s Cub". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Devil’s Cub" друзьям в соцсетях.