She said, with a challenging gleam in her eye: “I am rather tired or I assure you I should not indulge in a weakness I despise.”

“Egad, I believe you wouldn’t,” said his lordship.

Miss Challoner put the handkerchief away. “If you know what I must do next, I wish you would tell me, sir.”

“There’s only one thing you can do,” said his lordship. “You must marry me.”

The inn parlour spun round before Miss Challoner’s eyes. She shut them, unable to bear a sight so reminiscent of all she had undergone aboard the Albatross. “What?” she said faintly.

Vidal raised his brows. “You seem amazed,” he said.

“I am amazed,” replied Miss Challoner, venturing to open her eyes again.

“You have a remarkably pretty notion of my character, ma’am,” he said ironically.

Miss Challoner rose from her chair, and curtsied. “You are extremely obliging, my lord, but I must humbly decline the honour of becoming your wife.”

“You will marry me,” said his lordship, “if I have to force you to the altar.”

She blinked at him. “Are you mad, sir? You cannot possibly wish to marry me.”

“Of course I don’t wish to marry you!” he said impatiently. “I scarcely know you. But I play my cards in accordance with the rules. I have a number of vices, but abducting innocent damsels and casting them adrift on the world is not one of them. Pray have a little sense, ma’am! You eloped with me, leaving word of it with your mother; if I let you go you could not reach your home again until tomorrow night at the earliest. By that time — if I know your mother and sister at all — the whole of your acquaintance will be apprised of your conduct. Your reputation will be so smirched not a soul will receive you. And this, ma’am, is to go down to my account! I tell you plainly, I’ve no mind to become an object of infamy.”

Miss Challoner pressed a hand to her forehead. “Am I to marry you to save my face, or yours?” she demanded.

“Both,” replied his lordship.

She looked doubtfully at him for a moment. “My lord, I fear I am too tired to think very clearly,” she sighed.

“You’d best go to bed,” he said. He put his hand on her shoulder, and held her away from him, looking down at her. She met his gaze frankly, wondering what he would say next. He surprised her yet again. “Don’t look so worn, my dear; it’s the devil of a coil, but I won’t let it harm you. Good night”

Unaccountable tears stung her eyelids. She stepped back, and dropped a curtsy. “Thank you,” she said shakily. “Good night, my lord.”

Chapter VIII

Miss Challoner had pleaded fatigue, but it was long before she slept. Her desperate problem leered at her half through the night, and it was not until she had reached some sort of a decision that she could achieve slumber.

She was shocked to realize that for a few breathless moments she had forgotten Sophia in a brief vision of herself wedded to his lordship. “So that’s the truth, is it?” said Miss Challoner severely to herself. “You are in love with him, and you’ve known it for weeks.”

But it was not a notorious Marquis with whom she had fallen in love; it was with the wild, sulky, unmanageable boy that she saw behind the rake. “I could manage him,” she sighed. “Oh, but I could!” She did not permit herself to indulge in this dream for long. Marriage, on all counts, was out of the question. He did not give the snap of his fingers for her; he must marry, when the time came, some demure damsel of his own degree; and — the greatest bar of all — she could not steal a bridegroom from under Sophia’s nose.

Having disposed thus of his lordship, Miss Challoner set herself resolutely to think of her own future. Vidal had shown her the impossibility of a return to Bloomsbury; it would be equally impossible to seek shelter with her grandfather. After pondering somewhat drearily upon this sudden isolation, she dried her eyes, and tried to think of an asylum. At the end of two hours, being a female of considerable strength of mind, she decided that her wisest course would be to remain in France, to assume a new name, and to try to obtain a post as governess in a respectable French household.

She began, eventually, to compose a letter to her mother, and in the middle of a phrase which had become strangely involved, she fell asleep.

She partook of chocolate and a roll in bed next morning, and when she at length came downstairs to the private parlour, she was met by the discreet Fletcher, who informed her, not without a note of severity in his voice, that his lordship’s arm had broken out bleeding again in the night, and looked this morning uncommon nasty. His lordship was still abed, but meant to travel.

“Has a surgeon been sent for?” inquired Miss Challoner, feeling like a murderess.

“His lordship will not have a surgeon, madam,” said Fletcher. “It is the opinion of Mr. Timms, his lordship’s valet, and myself, that he should see one.”

“Then pray go and fetch one,” said Miss Challoner briskly.

Fletcher shook his head. “I daren’t take it upon myself, ma’am.”

“I don’t ask you to,” Miss Challoner replied. “Have the goodness to do as I bid you.”

“I beg pardon, madam, but in the event of his lordship desiring to know who sent for the surgeon — ?”

“You will tell the truth, of course,” said Miss Challoner. “Where is his lordship’s bedchamber?”

Fletcher eyed her with dawning respect. “If you will allow me to show you, madam,” he said, and led the way upstairs.

He went ahead of her into the room. Miss Challoner heard Vidal say. “Oh, let her come in!” and awaited no further invitation. She went in, and when the door had shut behind Fletcher, walked up to the big four-poster bed and said contritely: “I did hurt you. Indeed, I am sorry, my lord.”

Vidal was sitting up in bed, propped by pillows; his eyes looked a little feverish, and his cheeks were flushed.

“Don’t apologize,” he said. “You did very well for a beginner. I regret receiving you like this. I hoped you’d sleep later. Will you be ready to set forward at noon?”

“No, I fear I shall not,” she answered. “We will stay where we are for to-day.” She picked up a pillow from the floor, and arranged it carefully under Vidal’s injured arm. “Is that more comfortable, sir?”

“Perfectly, I thank you. But whether you are ready, or not, we start for Paris today.”

She smiled lovingly at him. “It’s my turn to play the tyrant, sir. You will stay in bed.”

“You are mistaken; I shall do no such thing.”

He sounded cross; she wanted to take his face between her hands and kiss away his ill-humour. “No, sir, I am not mistaken.”

“May I ask, ma’am, how you propose to keep me a-bed?”

“Why yes, I have only to remove your clothes,” Miss Challoner pointed out.

“Very wifely,” he commented.

She winced a little at that, but said without a tremor: “I have sent your man for a surgeon. Pray do not blame him.”

“The devil you have!” said his lordship. “I’m not dying, you know.”

“Certainly not,” replied Miss Challoner. “But you drank a great deal too much wine yesterday, and I have little doubt it is that that has made you feverish, and maybe inflamed the wound. I think you should be blooded.”

My lord regarded her speechlessly. She drew a chair up and sat down. “Do you feel well enough to talk with me for a few minutes, sir?”

“Of course I am well enough to talk with you. What do you want to talk about?”

“My future, if you please.”

He looked frowningly at her. “That’s my affair, ma’am.”

She shook her head. “It is kind in you, my lord, but I do not aspire to be your wife. I have thought very deeply, and I believe I know what will be best for me to do. May I tell you what I have decided?”

He said with a flash of humour: “There seems to be a vast deal of decision about you this morning, my dear. Tell me, by all means.”

She folded her hands in her lap; it occurred to him that she was a very restful woman. “What you said last night, my lord, was true; I cannot return to my home. You must not think that this will grieve me overmuch. I have never been very happy there. So I have formed a plan for my future which I believe to be tolerably sensible. If you will take me to Paris I shall be grateful for your escort. Once I am there it is my intention to seek a post in a genteel family as governess. I thought, perhaps you would be able to put me in the way of it, since I suppose you have a large acquaintance in Paris.”

His lordship broke in at this point. “My good child, are you proposing that I should recommend you to some respectable matron?”

“Couldn’t you?” asked Miss Challoner anxiously.

“I could, of course, but — Lord, I’d give a monkey to see the matron’s face!”

“Oh!” said Miss Challoner. “I see. It was stupid of me not to think of that.” She relapsed into profound thought. “Well, if I cannot find anyone to recommend me as a governess, I think I shall become a milliner,” she announced.

He stretched out his right hand, and clasped both of hers in it. He was no longer laughing. “I don’t often suffer from remorse, Mary, but you are fast teaching me. Come, can’t you stomach me as a husband?”

“Even if I could, my lord, do you think I would steal you from my sister? It was not for that I took her place.”

“Steal me be damned!” said his lordship rudely. “I’d never the smallest notion of marrying Sophia.”

“Nevertheless, sir, I could not do it. The very thought of marriage is absurd. You do not care for me nor I for you, and my estate is too far removed from yours.”

“What is your estate?” he asked. “Who was your father?”

“Does it matter?” she said.

“Not a whit, but you puzzle me. You did not get your breeding on the distaff side.”

“I was fortunate enough to be educated at a very select seminary, sir.”

“You were, were you? Who placed you there?”

“My grandfather,” answered Miss Challoner unexpansively.

“Your father’s father? Is he alive? Who is her

“He is a general, sir.”

Vidal’s brows drew together. “What county?”

“He lives in Buckinghamshire, my lord.”

“Good God, never tell me you are Sir Giles Challoner’s grandchild?”

“I am,” said Miss Challoner calmly.

“Then I am undone, and we must be married at once,” said Vidal. “That stiff-necked old martinet is a friend of my father’s.”

Miss Challoner smiled. “You need not be alarmed, sir. My grandfather has been very kind to me in the past, but he disowned my father upon his marriage, and has washed his hands of me since I choose to live with my mother and sister. He will not concern himself with my fate.”

“He’ll concern himself fast enough if he gets wind of his granddaughter in a milliner’s shop,” said Vidal.

“Of course I shall not become a milliner under my own name,” Miss Challoner explained.

“You won’t become one under any name, my girl. Make the best of it: marriage with me is the only thing for you now. I am sorry for it, but as a husband I believe you won’t find me exacting. You may go your own road — I shan’t interfere with you so long as you remain discreet — I’ll go mine. You need see very little of me.”

The prospect chilled Miss Challoner to the soul, but observing my lord’s heightened colour she judged it wiser not to argue with him any further at present. She got up, saying quietly: “We will talk of it again presently, my lord. You are tired now, and the surgeon will soon be here.”

He caught her wrist and held it. “Give me your word you’ll not slip off while I’m laid by the heels!”

She could not resist the temptation of touching his hand. “I promise I’ll not do that,” she said reassuringly. “I won’t leave your protection till we reach Paris.”

When the surgeon came he talked volubly and learnedly, with a great many exclamations and hand-wavings. His lordship suffered this for some time, but presently became annoyed and opened his eyes (which he had closed after the first five minutes) and disposed of the little surgeon’s diagnosis and proposed remedies in one rude and extremely idiomatic sentence.

The doctor started back as from a stinging nettle unwarily grasped: “Monsieur, I was informed that you were an Englishman!” he said.

My lord said, amongst other things, that he did not propose to burden the doctor with the details of his genealogy. He consigned the doctor and all his works, severally and comprehensively described, to hell, and finished up his epic speech by a pungent and Rabelaisian criticism of the whole race of leeches.

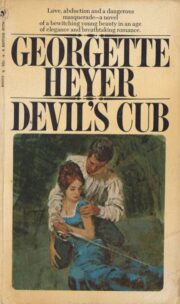

"Devil’s Cub" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Devil’s Cub". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Devil’s Cub" друзьям в соцсетях.